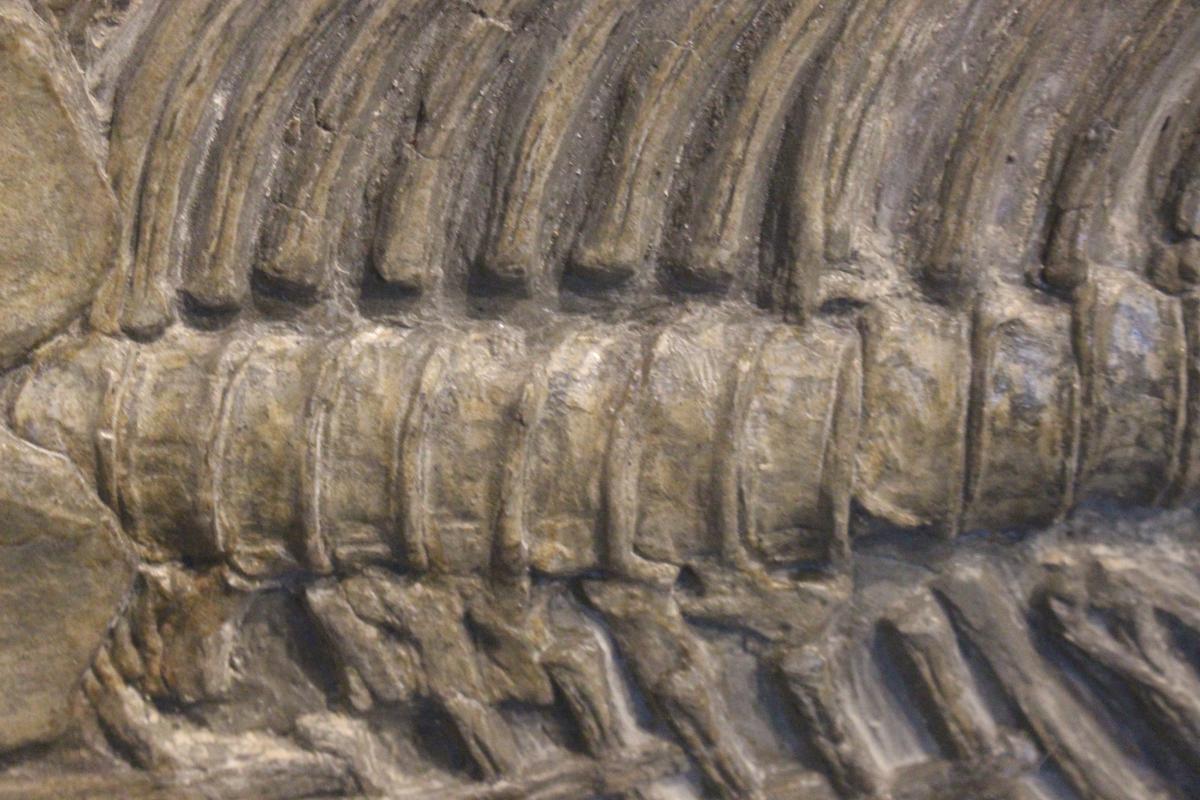

When writing up the Fossil Friday post last week, I was tempted to give a clue, but then thought better of it. You guys don’t need clues, right? Plus the clue I wanted to  drop would have narrowed the field too much. What I would have said was, “This creature’s backbone is a thing of beauty.” And so it is. You can’t really tell, but each vertebra is bi-concave. When assembled, they form a very rigid rod all the way down the animal’s back. Such rigidity is not great if agility and flexibility are key to your lifestyle, but it’s wonderful if you propel through water like a missile—and that’s just what this animal did.

drop would have narrowed the field too much. What I would have said was, “This creature’s backbone is a thing of beauty.” And so it is. You can’t really tell, but each vertebra is bi-concave. When assembled, they form a very rigid rod all the way down the animal’s back. Such rigidity is not great if agility and flexibility are key to your lifestyle, but it’s wonderful if you propel through water like a missile—and that’s just what this animal did.

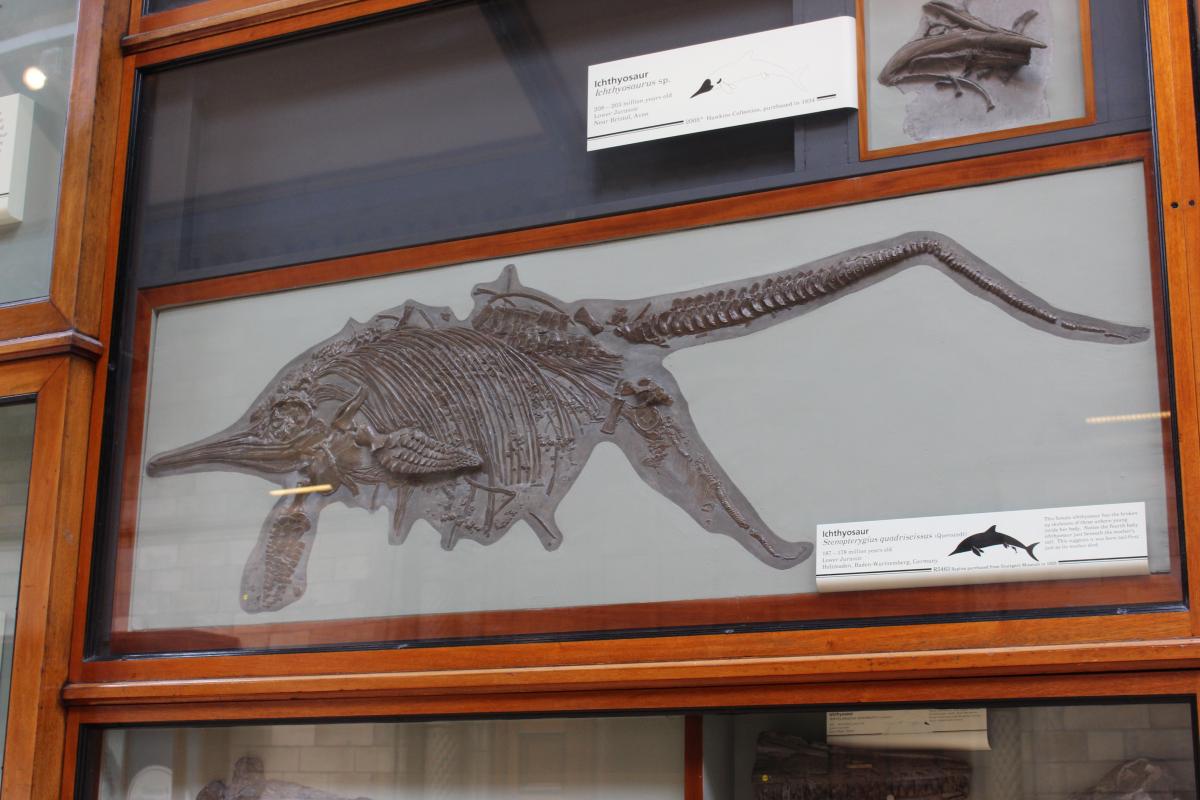

With that in mind, take a look at a wider shot of this week's Fossil Friday star:

What was it? An ichthyosaur’s forelimb. No, it’s not a fin; it’s a limb. The powerful paddle-shaped appendage is supported by the same “one bone, two bones, lots of little bones” pattern that unites all tetrapods.

Ichthyosaurs are not—I repeat not—dinosaurs. They lived at the same time as dinosaurs, but comparative anatomy tells us that they are not closely related. Unfortunately, although I can tell you what they’re not closely related to, I can’t tell you what they are closely related to. Ichthyosaurs, literally “fish lizards,” were so highly adapted and modified for an aquatic lifestyle that scientists aren’t sure where they came from. Some have suggested that they are an offshoot of the diapsids (the group that includes dinosaurs, crocodiles, mammals, and birds) while others think they are more closely associated with the highly enigmatic anapsids (the turtles).

The mysterious origins of ichthyosaurs and the other giant aquatic reptiles with which they shared the ocean (the plesiosaurs and pliosaurs) were represented in the fabulous cartoon guide to vertebrate evolution I wrote about months ago (and now have a print of hanging on my office wall. Man, I love that cladogram). Another group of Mesozoic aquatic reptiles, the mosasaurs (and no, they weren’t this big) have a clearer origin—certain characteristics closely align them with varanid lizards, such as the monitor and the Komodo dragon.

Anyway, back to ichthyosaurs! The earliest ichthyosaurs date back to the Triassic and tended to have bendier bodies that probably undulated to generate thrust. Later ichthyosaurs, such as our Fossil Friday specimen Temnodontosaurus integer from the Jurassic, had more rigid bullet-like forms that were moved through the water by powerful tail flukes. A very similar pattern occurred in whale evolution, with the earliest whales having flexible bodies well-suited for near-shore living and maneuvering, while later-to-evolve groups have more fusiform bodies that enable efficient open-water living. Interestingly, the ichthyosaur tail fluke was oriented like a shark’s tail, and moved side to side while whale flukes move up and down. I’ve always wondered why that was. If there are any PhD students out there, feel free to steal the idea, but make sure you report the findings back to me.

Ichthyosaurs went extinct several million years before the big asteroid-induced extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous. The reason for their extinction is just as mysterious as their origins.

These two big, open questions remain despite a robust fossil record that includes absolutely remarkable specimens. How remarkable? This remarkable: We know ichthyosaurs gave birth to live young, for example, because we have not one, but several, fossils of pregnant mothers and mothers in the process of giving birth.

These two big, open questions remain despite a robust fossil record that includes absolutely remarkable specimens. How remarkable? This remarkable: We know ichthyosaurs gave birth to live young, for example, because we have not one, but several, fossils of pregnant mothers and mothers in the process of giving birth.

Congratulations to Dan Phelps who quickly identified my mystery photo as an ichthyosaur paddle. Well done as usual!

Are you a teacher and want to tell us about an amazing free resource? Do you have an idea for a Misconception Monday or other type of post? Have a fossil to share? See some good or bad examples of science communication lately? Drop me an email or shoot me a tweet @keeps3.