Check out our entire series explaining the science involved in the coronavirus pandemic. Sign up to receive our coronavirus update each week.

Why will it take so long to develop a vaccine against coronavirus?

Let's figure this out together. Let's agree that our end goal is a vaccine that works, is safe, and can be mass produced and administered to hundreds of millions, if not billions, of people. Now, thinking like a scientist, how do you reach that end goal?

But first, a story.

Back in the 1700s, fear of smallpox was so intense that doctors recommended, and many people submitted to, a process called variolation. Doctors took a scraping from an active smallpox lesion and scratched it into the arm of the person hoping to be protected. This did indeed result in immunity to smallpox, at least in those that recovered from the process. Two to three percent of variolated persons, however, developed a case of smallpox serious enough to kill them.

That’s right, people were willing to submit themselves and their children to a procedure that had a 2-3% chance of killing them. That sounds crazy, but given that smallpox had a 20-60% fatality rate and showed up year after year, it was a good bet at the time.

Also of interest, historically, is how the medical community convinced local authorities and their patients that this process worked. When the idea of variolation reached North America, most physicians were skeptical. Only two–Cotton Mather and Zabdiel Boylson–were enthusiastic proponents. When a smallpox epidemic began, they variolated as many volunteers as they could persuade. Then they compared the mortality rate among those that were variolated and those that were not. Mather and Boylston were able to show that the process "worked"–only 2% of their patients died, compared to 14% among the unvariolated.

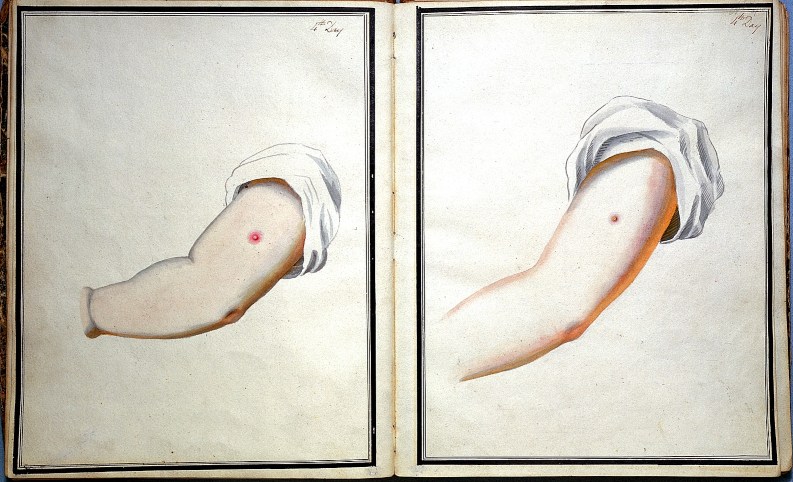

Still, a 2% mortality rate is not so great. So it was a huge improvement in 1796 when Edward Jenner–having noticed that dairymaids who had been exposed to cowpox were immune to smallpox—had the idea that if you could spread cowpox from one person to another, the recipients would also become immune to smallpox. To test his theory, he took a sample from a dairymaid’s cowpox lesion and scratched it into the arm of a local boy. The boy was briefly and mildly ill and then recovered. Two months later, Jenner took a sample from an actual smallpox lesion and scratched it into the boy’s arm.

Wait, what????!!!! Smallpox had a mortality rate of 20-60%—this was an incredibly dangerous experiment!

But it worked. The boy did not develop smallpox.

Phew.

We are no longer willing to scratch an infectious agent into a child's arm to see if it will bring immunity to a deadlier infectious agent. So what are the steps we follow now? Each step represents a great topic for a group of your students to dig into—I'll just give a general idea and an estimate of how long the step might take.