When I decided to leave my PhD program in paleontology to pursue other endeavors, one of the reasons was a lab mate named Corwin Sullivan. Not because he was smelly or mean or anything negative—in fact, it was exactly for the opposite reason: Corwin was (and is) awesome. His intense passion for research was inspiring, as was his selflessness when it came to giving his time and attention to the less experienced  in our lab—namely, me. Talking paleontology and evolution with Corwin was always intense and all-consuming. I’d go to him with one question and walk about with about ten dissertations’ worth of new questions. So how could my fabulous and brilliant friend Corwin be a reason for me to leave research? Because I just couldn’t muster as much enthusiasm and passion for it as Corwin did. Corwin is exactly who should be conducting research. As for me, I found that I was much happier doing other things, like talking to people about the stuff Corwin had taught me. So off I went to do just that, while Corwin kept researching away. He is now a professor at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) in Beijing, China.

in our lab—namely, me. Talking paleontology and evolution with Corwin was always intense and all-consuming. I’d go to him with one question and walk about with about ten dissertations’ worth of new questions. So how could my fabulous and brilliant friend Corwin be a reason for me to leave research? Because I just couldn’t muster as much enthusiasm and passion for it as Corwin did. Corwin is exactly who should be conducting research. As for me, I found that I was much happier doing other things, like talking to people about the stuff Corwin had taught me. So off I went to do just that, while Corwin kept researching away. He is now a professor at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) in Beijing, China.

I find it downright delightful, therefore, that I am now writing the introduction to a series of blog posts about an exciting fossil that Corwin helped to describe. I’m doing what I do best, and Corwin is doing what he does best. It’s very satisfying, really.

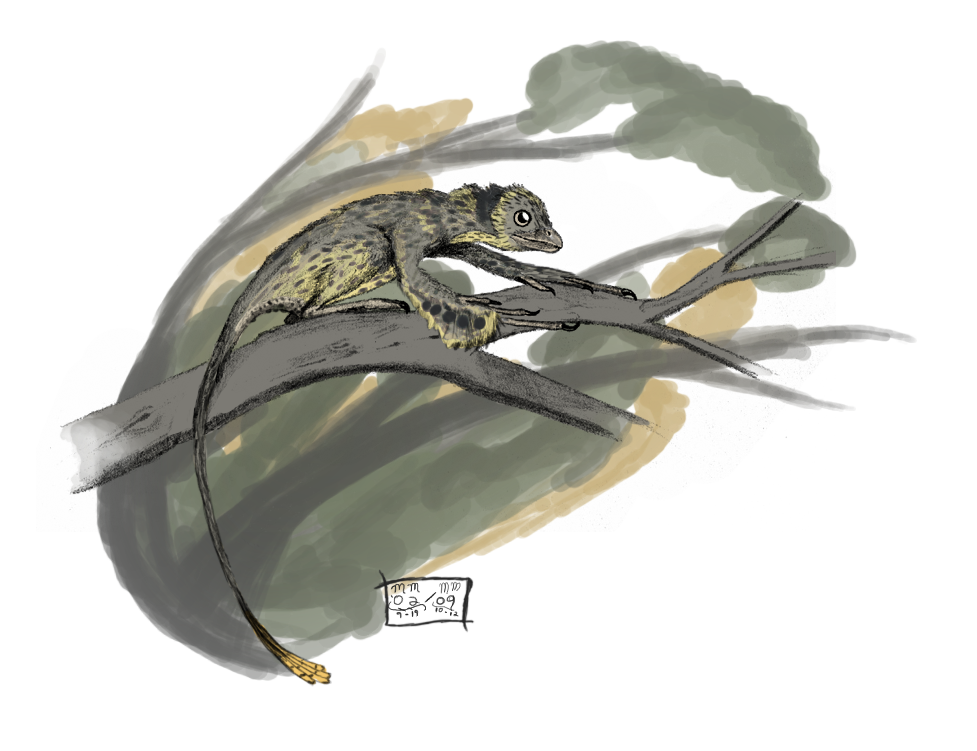

So what is this new fossil? Yi qi, described in the media as a “batwinged dino-pigeon,” which, I have to say, is a pretty apt description. Corwin sent me the proof of the Nature paper as well as the IVPP’s press release last week. I read them, and a bunch of media reports, and I knew I’d be bringing Yi to the blog. But instead of the typical me telling you what’s cool about a fossil, I thought I’d get Corwin to do it. We’ve been e-mailing back and forth and the result is a three-part interview. Read on for insights into why Yi is special, why Nature reviewers felt they had to challenge the description at first, why we can’t know (yet) how Yi flew, why there are often giant lags between discovery and description in vertebrate paleontology, and how Yi might make its way to classrooms.

SK: Help us to put this new discovery in its rightful place on the phylogenetic tree—do we need to toss out everything we know about feathered dinosaurs, to “upturn the tree”? (Journalists are always talking about upturning the tree, aren’t they? Upturn a twig maybe, but the whole tree? Rarely!) Or does it fit somewhere nicely; it’s just weird?

CS: Yi qi fits nicely among the Scansoriopterygidae, a somewhat enigmatic group of theropods close to the origin of birds. There are two other definite Jurassic scansoriopterygids, Epidendrosaurus and Epidexipteryx, and Zhongornis from the Cretaceous might be a third member of the group, so Yi qi is either number three or number four. All these animals, though, including Yi qi, are known from rather imperfect specimens, so some aspects of their anatomy are still unclear. However, we do know that scansoriopterygids are closely related to birds—they’re either the closest relatives of birds among non-avian dinosaurs, or a couple of nodes further away from birds, depending on whose phylogenetic analysis you support.

CS: Yi qi fits nicely among the Scansoriopterygidae, a somewhat enigmatic group of theropods close to the origin of birds. There are two other definite Jurassic scansoriopterygids, Epidendrosaurus and Epidexipteryx, and Zhongornis from the Cretaceous might be a third member of the group, so Yi qi is either number three or number four. All these animals, though, including Yi qi, are known from rather imperfect specimens, so some aspects of their anatomy are still unclear. However, we do know that scansoriopterygids are closely related to birds—they’re either the closest relatives of birds among non-avian dinosaurs, or a couple of nodes further away from birds, depending on whose phylogenetic analysis you support.

SK: When did you first see Yi and what did you think? Did you and the team know it was something different right away?

CS: When I first saw Yi qi, I was visiting the Tianyu Museum, in Shandong Province, with my colleagues Xu Xing and Jingmai O’Connor from the IVPP. That was in the spring of 2014, and of course it wasn’t Yi qi at that point—it was just an undescribed, unnamed fossil. Xu was already working on the specimen together with Zheng Xiaoting, the director of the Tianyu Museum, but they were happy to show it to Jingmai and me as something that might interest us. All four of us were baffled by the strange, rod-like structures extending from the wrists of the specimen. Dinosaurs aren’t supposed to have bones in that position, but the structures certainly looked bony. We were trying to explain them away as some kind of soft-tissue feature, but not having much luck—none of us could think of a hypothesis that passed the sniff test, even though both Xu and Jingmai have a lot of experience with interpreting feathers and other preserved soft tissue features in fossils from northeast China (I’m more of a bone man, myself). So we knew the fossil was a strange scansoriopterygid, but we were a little baffled by it.

A couple of months later, I was reading a lot of stuff about flying and gliding vertebrates for a totally unrelated project. I came across a passage in a textbook that said modern “flying” squirrels (which actually glide, of course) have a cartilaginous strut, which helps to support the membranous wing, extending from either the wrist or the elbow. At the mention of a strut extending from the wrist, my mind immediately jumped back to the strange little dinosaur I’d seen in Shandong. At first the analogy seemed very far-fetched, but as Xu Xing and I began looking into it more, we became convinced that it held some water. That was when Xu invited me to join the project.

What we found was two critical, essentially independent pieces of evidence for a membranous wing in Yi qi: the rod-like bone coming out of each wrist, and the patches  of sheet-like soft tissue preserved alongside the rod-like bone and the fingers. Xu Xing spotted the patches of sheet-like tissue, which certainly lend themselves to interpretation as pieces of a flight membrane.

of sheet-like soft tissue preserved alongside the rod-like bone and the fingers. Xu Xing spotted the patches of sheet-like tissue, which certainly lend themselves to interpretation as pieces of a flight membrane.

SK: You mentioned that it took a while to get Nature to accept the paper. What happened?

CS: The paper went through multiple rounds of peer review, which is not unusual. At first the reviewers were very skeptical, which isn’t surprising because the whole idea of a scansoriopterygid with a membranous wing supported by a rod-like bone is pretty radical. The reviewers had every reason to kick the tires good and hard, and demand that we back up our claims by documenting the evidence thoroughly. Their criticisms of our manuscript made the final published version a lot stronger, so I’d say this was a case in which the peer review process worked just like it’s supposed to.

SK: Yes, I can see how the description of a “batwinged dino-pigeon” might raise some eyebrows. But on the other hand, flight! Flight always gets people’s attention! In my book, if Ed Yong writes about you, you’ve made it. Are you happy with the reception that the discovery has had? Have you fielded any interesting or unusual press inquiries?

CS: Ed Yong’s article was very well done, and I’ve read a couple of other good, in-depth pieces of similar quality. Most of the write-ups I’ve seen in the media have been shorter and more superficial, but none have struck me as misleading or clueless, so yes, I’m pleased with the way things have gone. Virtually all of the questions I’ve had from the press have been reasonable and substantive. A couple of journalists I communicated with needed help coming to grips with the pronunciation of Yi qi (roughly “ee chee”), which is not surprising. One joked that her cat might want to eat Yi qi if it were alive today.

or clueless, so yes, I’m pleased with the way things have gone. Virtually all of the questions I’ve had from the press have been reasonable and substantive. A couple of journalists I communicated with needed help coming to grips with the pronunciation of Yi qi (roughly “ee chee”), which is not surprising. One joked that her cat might want to eat Yi qi if it were alive today.

We may never know how tasty today’s domestic felines would have found Yi qi. But can we do better in assessing whether, and if so how, the batwinged dino-pigeon flew? Read all about it in Part 2.

Are you a teacher and want to tell us about an amazing free resource? Do you have an idea for a future Misconception Monday or other post? See some good or bad examples of science communication lately? Drop me an email or shoot me a tweet <at>keeps3.