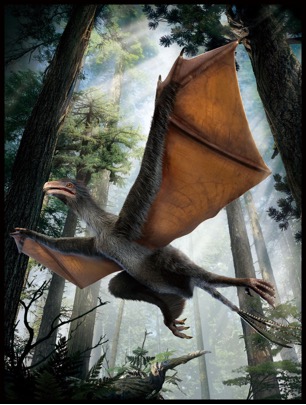

In Part 1, I introduced you to my friend Corwin Sullivan of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) in Beijing, China, co-describer of the enigmatic Yi qi fossil that hit the media last week. Yi qi—the name means, roughly, “strange wing”—is a close bird relative with wings sort of like those of a bat. So naturally, everyone wants to know if and how this critter flew. But as Corwin explains below, the researchers don’t know something critical about Yi, which inhibits their ability to make firm inferences when it comes to how Yi qi might have flown.

---

SK: With this discovery, you’ve really added a new wrinkle to the whole how-did-flight-evolve question—which I’ve always found a little silly, actually. I remember when we  were in graduate school, and in the same week in 2003, Nature’s cover story was about the newly discovered dinosaur group known as microraptors from China, with four wings that suggested gliding, while Science’s cover story was about Ken Dial’s study suggesting that flapping underdeveloped wings helped baby birds run up hills. So it was trees-down in Nature and ground-up in Science. I remember thinking, “Why does it have to be one or the other? Doesn’t it make sense that both happened?” Are you surprised to have found this new category of flying dinosaur? Do you think there are other variations out there waiting to be found?

were in graduate school, and in the same week in 2003, Nature’s cover story was about the newly discovered dinosaur group known as microraptors from China, with four wings that suggested gliding, while Science’s cover story was about Ken Dial’s study suggesting that flapping underdeveloped wings helped baby birds run up hills. So it was trees-down in Nature and ground-up in Science. I remember thinking, “Why does it have to be one or the other? Doesn’t it make sense that both happened?” Are you surprised to have found this new category of flying dinosaur? Do you think there are other variations out there waiting to be found?

CS: I certainly think it’s plausible that different theropod species close to the origin of birds could have been in the trees, on the ground, and everywhere in between, and found feathers and other incipient flight-related structures to be useful in all these contexts. After all, it’s not uncommon for closely related species in the modern world to vary in their ability and inclination to climb trees. So yes, I agree that the “ground-up” and “trees-down” accounts of the origin of flight aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive.

We already know that the origin of birds was anything but an orderly progression along some continuum with, say, Caudipteryx at the beginning and Woody Woodpecker at the end. There was a lot of anatomical and functional variation among dinosaurs closely related to birds, and for that matter among early birds themselves, with different species close to the transition having different combinations of flight-related features. So it isn’t surprising to see a new kind of aerial dinosaur turn up, and I’m sure that there are more out there waiting to be found. But what is surprising about Yi qi is the sheer starkness of the difference between its membranous wing, supported by a rod-like bone, and the feather-based wings that are typically present in birds and their close relatives. The wing of Yi qi seems less like a new variation on the usual theme than like a whole new theme of its own, and in that sense it’s a very exciting discovery indeed.

We already know that the origin of birds was anything but an orderly progression along some continuum with, say, Caudipteryx at the beginning and Woody Woodpecker at the end. There was a lot of anatomical and functional variation among dinosaurs closely related to birds, and for that matter among early birds themselves, with different species close to the transition having different combinations of flight-related features. So it isn’t surprising to see a new kind of aerial dinosaur turn up, and I’m sure that there are more out there waiting to be found. But what is surprising about Yi qi is the sheer starkness of the difference between its membranous wing, supported by a rod-like bone, and the feather-based wings that are typically present in birds and their close relatives. The wing of Yi qi seems less like a new variation on the usual theme than like a whole new theme of its own, and in that sense it’s a very exciting discovery indeed.

SK: Yes, yes, very interesting, but…okay, I can’t help it and I’m going to ask anyway: trees-down or ground-up? What do we know about Yi’s flight abilities?

CS: Well, we don’t know the shape or size of the membranous wing, or even the form of the tail (which could have an important impact on the animal’s aerodynamics), which makes it difficult to say very much about how Yi qi moved through the air. One argument we do make in the paper, although it’s not backed up by any kind of quantitative analysis, is that flapping flight requires rapid, fairly elaborate forelimb movements, whereas the rod-like bone coming out of the wrist must have been a fairly unwieldy structure. With that in mind, I suspect that Yi qi was mostly a glider, though it might have combined gliding with some awkward flapping. Gliders pretty well have to start from some kind of elevated perch, so I guess that implies trees down rather than ground up for Yi at least.

CS: Well, we don’t know the shape or size of the membranous wing, or even the form of the tail (which could have an important impact on the animal’s aerodynamics), which makes it difficult to say very much about how Yi qi moved through the air. One argument we do make in the paper, although it’s not backed up by any kind of quantitative analysis, is that flapping flight requires rapid, fairly elaborate forelimb movements, whereas the rod-like bone coming out of the wrist must have been a fairly unwieldy structure. With that in mind, I suspect that Yi qi was mostly a glider, though it might have combined gliding with some awkward flapping. Gliders pretty well have to start from some kind of elevated perch, so I guess that implies trees down rather than ground up for Yi at least.

SK: So in the paper, you modeled a few different possibilities for how Yi’s wing might have looked. Is there anything else you can do to glean more information from the fossils on hand about how Yi might have flown, or is this really a case in which further fossil discoveries will be necessary?

CS: Aerodynamic modelling of the different possibilities, either with fluid dynamics software or using the old-fashioned method of putting physical reconstructions in a wind tunnel, could potentially yield some insights. That kind of thing is a little beyond the expertise of the team that described Yi qi, though—we’re basically just a bunch of palaeontologists, so we’d have to find some good collaborators.

---

So we’ll have to wait to know more about if and how Yi qi might have flown. But don’t despair: there’s more to say about everybody’s new favorite batwinged dino-pigeon, as you’ll discover in part 3. For now, I’ll leave you with this last tidbit: Yi qi is now the shortest dinosaur binomial. (There are apparently three three-letter dinosaur genera, Kol, Mei, and Zby [Zby?].) And it’s tied for the shortest binomial overall with Ia io, the great evening bat. So the two organisms with the shortest scientific names are both bat-winged. Cool, and useless knowledge, brought to you by NCSE. You’re welcome.

Are you a teacher and want to tell us about an amazing free resource? Do you have an idea for a future Misconception Monday or other post? See some good or bad examples of science communication lately? Drop me an email or shoot me a tweet <at>keeps3.