My advice of the day?

My advice of the day?

Never pass up a chance to hang out with science teachers!

The occasion was the 2017 awards luncheon of the California Science Teachers Association (CSTA). The National Center for Science Education was being honored with the 2017 Distinguished Contributions Award, for our work supporting the California Science Framework review process, and our help in providing teachers with guidance about how to respond to the Heartland Institute’s mailing of misleading climate propaganda to California teachers. It was awfully nice of CSTA to recognize NCSE since in my view, it’s teachers who deserve the accolades.

For me, the highlight of the luncheon was the keynote address by Page Keeley, who is best known for her work developing assessment tools that probe students’ understanding of science concepts, as opposed to their ability to memorize facts. Keeley gave a couple of examples of how using these conceptual probes before starting to teach a topic can provide the teacher with a lot of insight into where their students are coming from, and therefore, where misconceptions may lurk.

The first example involved heat. For this activity, students are asked: what happens if you put a thermometer inside a mitten? Will the temperature go up, go down, or stay the same? The answer is obvious to adults, obvious to the point that we might not think to ask children what they think. But it turns out that most kids think that the temperature will go up, because, after all, mittens are warm! That’s why we wear them in the winter! Keeley assured us that kids really commit to this idea—when the temperature doesn’t rise, they suggest leaving the thermometer in the mitten longer, or even that the thermometer must be defective! Only when they put the thermometer in the mitten while they are wearing it, and the temperature rises, do they realize that the warmth they enjoy in mittens isn’t coming from the mittens, it’s coming from their hands; the mittens are acting as an insulator.

The first example involved heat. For this activity, students are asked: what happens if you put a thermometer inside a mitten? Will the temperature go up, go down, or stay the same? The answer is obvious to adults, obvious to the point that we might not think to ask children what they think. But it turns out that most kids think that the temperature will go up, because, after all, mittens are warm! That’s why we wear them in the winter! Keeley assured us that kids really commit to this idea—when the temperature doesn’t rise, they suggest leaving the thermometer in the mitten longer, or even that the thermometer must be defective! Only when they put the thermometer in the mitten while they are wearing it, and the temperature rises, do they realize that the warmth they enjoy in mittens isn’t coming from the mittens, it’s coming from their hands; the mittens are acting as an insulator.

That was fun, but left all us adults feeling pretty smug; we all knew the right answer. The second example turned out to stump most of the roomful of science nerds.

Before I tell you about it, I should say that Keeley was careful to warn us that it’s terribly important that students not be admonished for choosing the wrong answer. That notion? That mittens are warm, so the temperature should go up inside them? It’s a perfectly reasonable hypothesis. You can make a good argument for it. It’s testable. Okay, so it turns out not to be the way the world works, but that’s what experiments are for: do I understand the world correctly, or not? When students are free to test their ideas for themselves, in other words, actually do science, they learn so much more.

I was glad that Keeley made that important point before getting to the last exercise, because, boy, did my whole table full of scientists and teachers get it wrong!

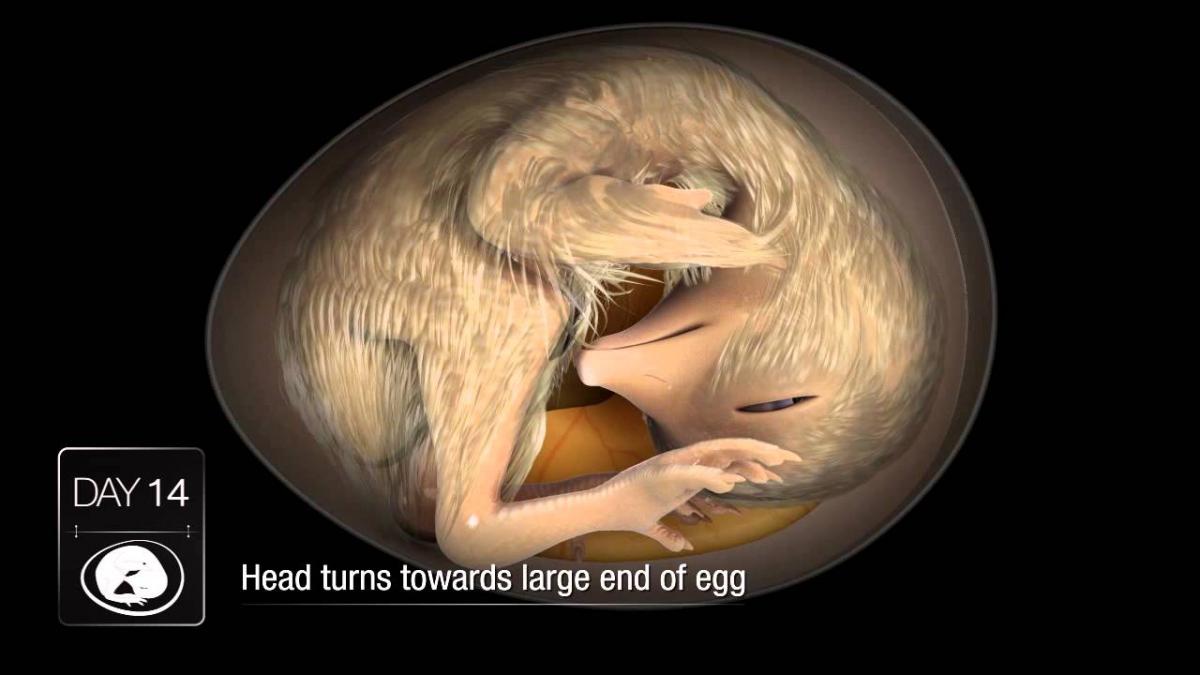

She showed a video of a chick developing within an egg. It was beautiful, and fascinating, to see the undifferentiated cells gradually grow into the baby bird, with the orderly appearance of limb buds, beak, claws, and feathers. When the chick pecked its way out of the shell and stood blinking in the daylight, we all cheered. Then Keeley asked the question: If you weighed the egg just after fertilization and then again just before the chick was born, would it weigh more, less, or exactly the same?

She showed a video of a chick developing within an egg. It was beautiful, and fascinating, to see the undifferentiated cells gradually grow into the baby bird, with the orderly appearance of limb buds, beak, claws, and feathers. When the chick pecked its way out of the shell and stood blinking in the daylight, we all cheered. Then Keeley asked the question: If you weighed the egg just after fertilization and then again just before the chick was born, would it weigh more, less, or exactly the same?

I’m not going to tell you what we all said, or what the “right” answer is. You make a hypothesis for yourself, then go look it up. You’ll find that there are a lot of different science concepts you might apply in your thinking: conservation of matter, membrane permeability, closed vs open systems, metabolic energy … which ones apply here? Why? It’s pretty fun to find out the answer, isn’t it? And for teachers, giving the students a genuine question and then guiding them through the process of developing and testing hypotheses about it not only provides a more authentic experience of science, it also allows plenty of opportunities to identify and correct possible misconceptions.

Finding out the answer to that question was fun, but you know what the real take-home lesson is: science education, even in elementary school, can be challenging, and intriguing, and rewarding. Just like real science. And that’s why I love hanging out with science teachers and am proud of NCSE for trying to make their lives easier when it comes to teaching topics that have the potential to, um, ruffle feathers.

Mitten photo by Rachel Beer, used under CC BY-NC 2.0 license.