On Thursday, June 18, 2015, Pope Francis is due to deliver his first encyclical, a major document laying out an interpretation of Catholic doctrine. His theme will be the environment, and especially climate change.

On Thursday, June 18, 2015, Pope Francis is due to deliver his first encyclical, a major document laying out an interpretation of Catholic doctrine. His theme will be the environment, and especially climate change.

A draft of the letter has leaked, which I’ve spent a bit of time trying to mash through automatic translators. The results are predictably messy, so I think I’ll reserve commentary on the document until the official English translation is issued. Eric Holthaus has some reliable translations of a few important bits, if you’re curious. Encouragingly, the document was written with guidance from actual climate scientists, and the Pope could draw on his training as a chemist, the long Jesuit tradition of scientific research, and his namesake Francis of Assisi’s love of nature.

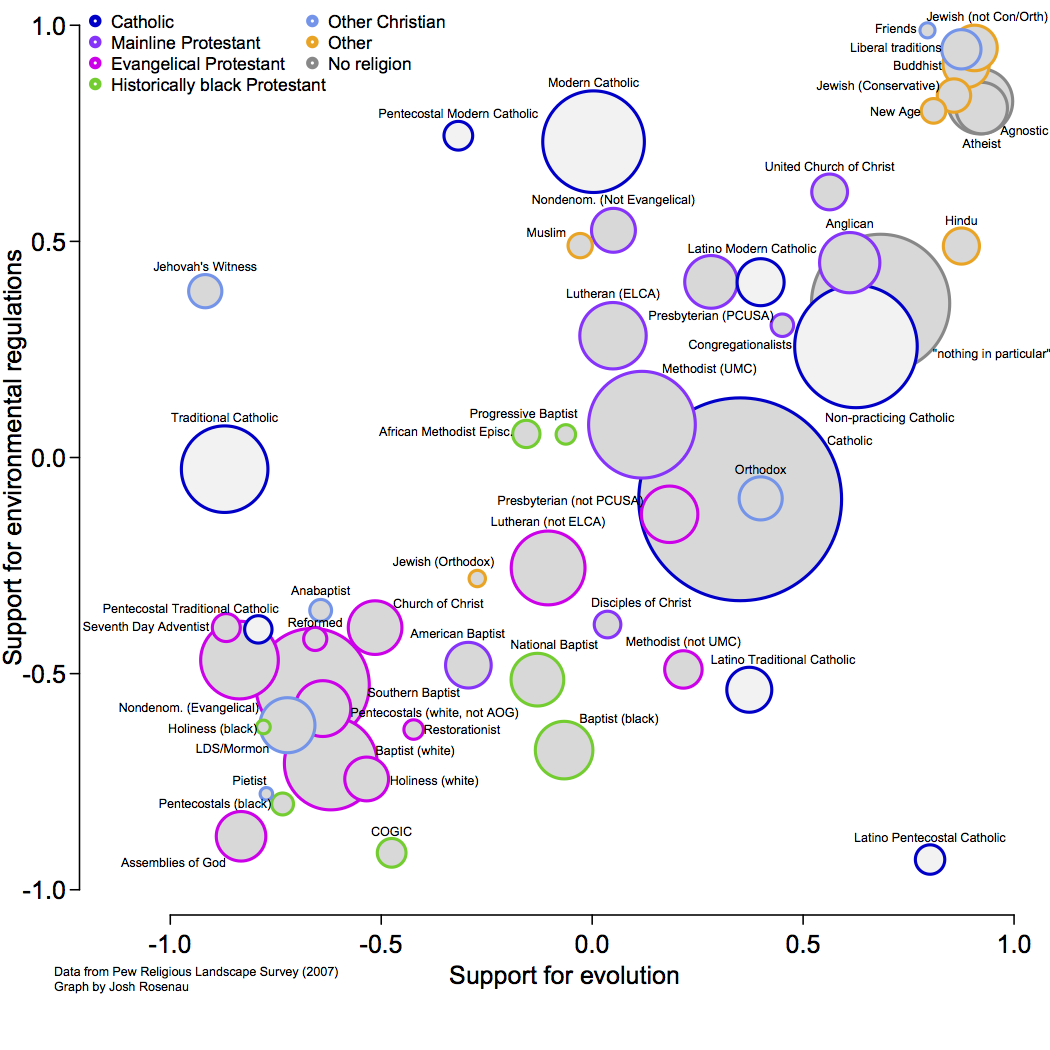

In anticipation of what promises to be an important document, and one which will challenge the leadership of the US Catholic hierarchy, I thought I’d delve into an element of the Big Chart of Religion, Evolution, and the Environment that I’ve been meaning to unpack.

In my original chart, I lumped all the Catholics into one circle, since there are no formal or denominational subdivisions to rely on. But Tobin Grant, who inspired the structure of the original chart, has a useful taxonomy of subgroups, which I borrowed for this figure, in which the Catholic subgroups are shown by a lighter circle (click the chart below for a high-res PDF):

The most important distinctions here are between Non-practicing Catholics and those who attend church fairly often, between Traditional Catholics and Modern Catholics, and between Catholics of Latin American ancestry and those of other backgrounds. Traditional Catholics and Modern Catholics are separated by their answer to this question:

My church or denomination should:

1 preserve its traditional beliefs and practices OR

2 adjust traditional beliefs and practices in light of new circumstances OR

3 adopt modern beliefs and practices.

Traditional Catholics pick the first; Modern Catholics opt for the latter two. Non-practicing Catholics are the third largest group in that chart, behind Catholics as a whole and people who don’t feel a strong affiliation with any religion. They are almost as pro-evolution and pro-environment as the religious Nones.

Modern Catholics strongly favor environmental regulation, to a far greater extent than they endorse evolution. Traditional Catholics are evenly split on the environment, but quite resistant to evolution. Latino Catholics as a whole are quite supportive of evolution (more so than Modern Catholics), but there’s a broad range of responses on the environment question among those who are more traditional, more modern, and those who’ve adopted Charismatic and Pentecostal practices into their Catholicism (this borrowing from Protestant traditions is increasingly common, and may bring with it dominionist and millennialist ideologies that decrease concern for Earth). Note that these data are from 2007, before Francis ascended to the papacy, and cultural shifts in the last eight years may have changed some of these patterns already.

There’s little doubt that Pope Benedict XVI was of the Traditional bent, fitting (Catholic) William F. Buckley’s definition of a conservative as “someone who stands athwart history, yelling Stop.” Pope Francis has hardly adopted modern beliefs and practices (women still can’t get ordained, you can't get married if you're divorced or gay, and the encyclical appears to skip any discussion of population growth and its effect on the environment rather than challenge the Church’s widely-ignored doctrine on contraception). But he’s certainly looking for ways to adjust traditions in light of new circumstances, and this encyclical is one such opportunity.

As the first Latin American pope, we can expect this encyclical to have an especially large effect on Latino and Latina Catholics, and to shore up environmental support among the Pope’s fellow Modern Catholics. It’s harder to predict how it’ll affect the Non-practicing Catholics. On one hand, they identify enough with Catholicism that the Pope’s word probably carries some weight, but if they were especially concerned with the Pope’s opinion, they’d probably attend church more than a few times a year. Among the more conservative Catholics, there may even be a backlash, the sort of revanchism one sees among people who preserve the pre-Vatican II Tridentine Mass. But some of the Traditional Catholics are likely to adhere to the tradition of deference to an encyclical and shift their views on the environment.

Most interesting will be how clergy respond. Already, we see evidence of a split between the approach of Latino Catholics and white Catholics. Only one in five white Catholics say that their priest talks about climate change, while a whopping 70% of Latino Catholics say the same (hopefully they'll all sign the Clergy Climate Letter!). We can hope that the papal encyclical will help narrow that gap, and with it the substantial gap in perceptions of climate change; Latino Catholics are 50% more likely to accept the reality of climate change than white Catholics. If more priests start taking their cue from the Latino Modern Catholic-in-chief, it could have a dramatic effect on the long-delayed effort to confront climate change.