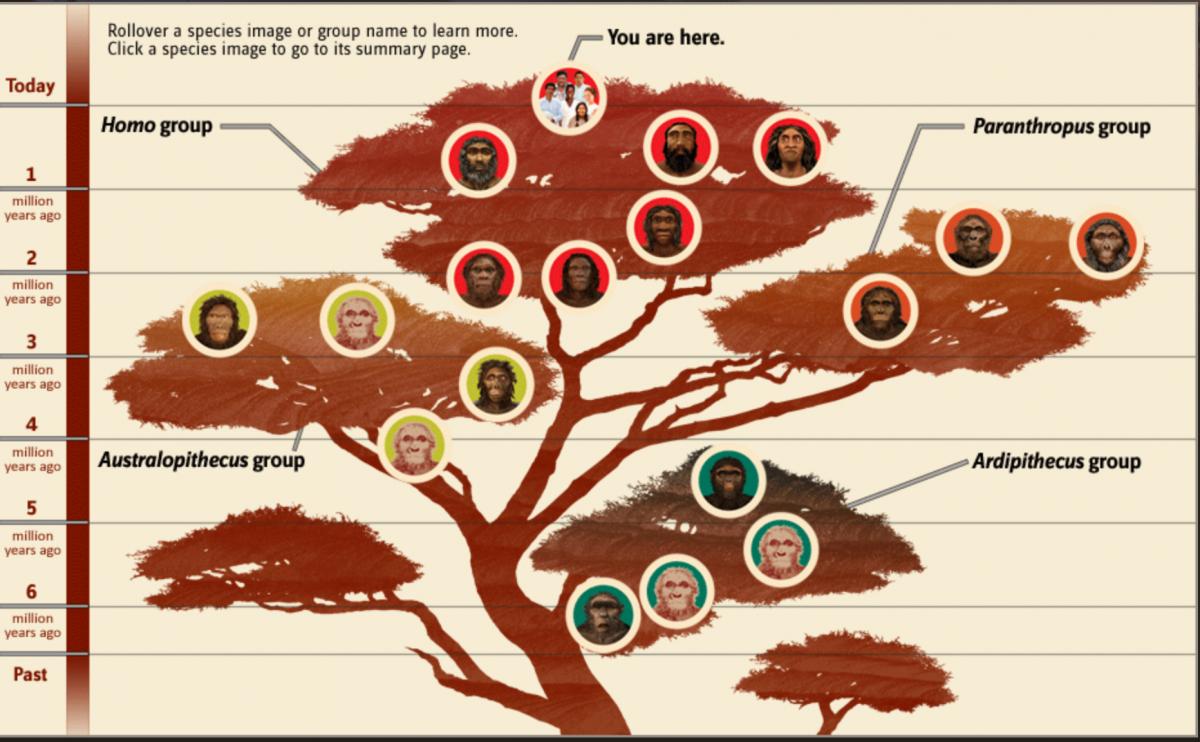

Before about a month ago, my knowledge and understanding of human evolution was pretty limited. I knew the basics: lots of different hominins (species more closely related to modern humans than to modern chimps) living together in Africa, then humans (species of the genus Homo) appear. A few human species move out of Africa and spread all over the world. During that time, our species and the Neanderthals interbred a bit and swapped some genes; and then there was just us, Homo sapiens: like the cheese, we stood alone.

But recently, I started to work with Briana Pobiner, a paleoanthropologist with the Smithsonian and all-around awesome person, on a classroom resource for HHMI’s BioInteractive. The activity, which will support the short film, Great Transitions: The Origin of Humans, requires students to compile data on many different skulls and use those data to infer relationships and come to conclusions about our evolutionary past. As a result of all this work, I now know my hominins from my hominids, my Australopithecus from my Ardipithecus. I don’t know it all, but I know a lot more than I used to. So I was all ears and eyes when a story about a new human jawbone discovered in Ethiopia filled the airwaves and newspapers last week. According to the reports, this new fossil “filled a gap” in human evolution. Really? Tell me more…

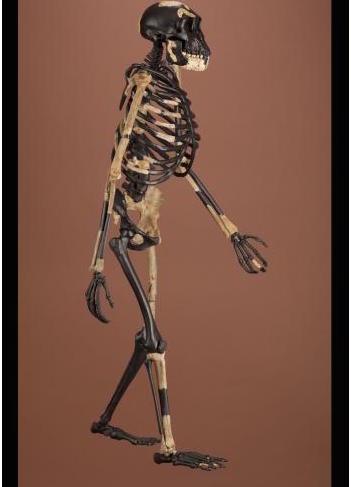

The fossil was found in 2013 in the Afar region of Ethiopia, which was also the resting place of the famous Lucy (species Australopithecus afarensis) and Ardi (Ardipithecus ramidus). Both Lucy and Ardi were remarkably informative specimens. There were 110 pieces found from Ardi, including bones from her feet, legs, arms, hands, pelvis, and skull. Lucy was not quite so complete, but there were still many bones recovered. This new fossil on the other hand? Not so much—we have just a few pieces of the lower left jaw with five embedded teeth. That’s it. So why all the hoopla?

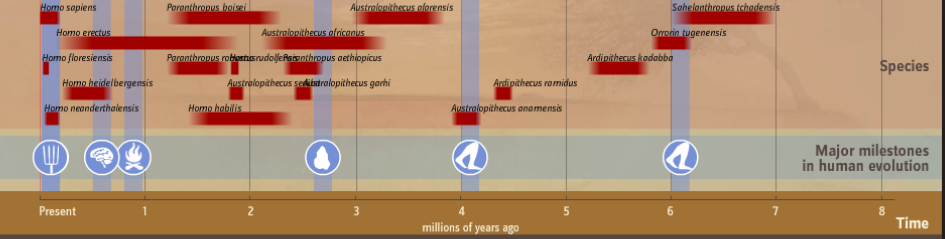

Well, the age of the fossil is the first thing of note—it’s 2.8 million years old. (Pop quiz! Did they get this date by a) directly dating the fossil itself or b) directly dating the volcanic rock in which it was found?) This age is significant because there has been a notable gap in the hominid fossil record in  East Africa that stretches from the disappearance of Lucy’s genus (Australopithecus), about 3 million years ago, to the appearance of our genus (Homo), about 2.4 million years ago. Some fossils have been found in that gap, but the species they represent are not good candidates for a direct ancestor of the Homo genus. Paleoanthropologists have inferred that Homo evolved from Australopithecus in this region but it’s hard to test that hypothesis without any fossil data. (Pop quiz! Did Australopithecus most likely a) gradually morph into Homo or b) split into multiple subpopulations, one of which gradually accumulated changes eventually resulting in Homo?) The “gap” therefore that The New York Times refers to in its title “Jawbone fossil fills a gap in human evolution” is this roughly half-million-year gap between Australopithecus afarensis and Homo habilis in East Africa. Cool? Cool.

East Africa that stretches from the disappearance of Lucy’s genus (Australopithecus), about 3 million years ago, to the appearance of our genus (Homo), about 2.4 million years ago. Some fossils have been found in that gap, but the species they represent are not good candidates for a direct ancestor of the Homo genus. Paleoanthropologists have inferred that Homo evolved from Australopithecus in this region but it’s hard to test that hypothesis without any fossil data. (Pop quiz! Did Australopithecus most likely a) gradually morph into Homo or b) split into multiple subpopulations, one of which gradually accumulated changes eventually resulting in Homo?) The “gap” therefore that The New York Times refers to in its title “Jawbone fossil fills a gap in human evolution” is this roughly half-million-year gap between Australopithecus afarensis and Homo habilis in East Africa. Cool? Cool.

So which genus does the fossil belong to, and how do we know? Based on jaw and tooth morphology (remember, a lot of the fossil record of mammals consists of teeth), it’s clearly Homo. The heretofore oldest Homo fossil is that of a 2.4-million-year-old Homo habilis, which means that this single fossil extended the known range of our genus nearly a half million years. Cool? Super cool!

Two papers on the discovery appear in Science, and in the articles the scientists describe how the jaw bone shows transitional characteristics between Australopithecus and Homo, which supports the hypothesis that the latter evolved from the former. Cool, cool, and cool. Paleoanthropologists say that it is “unlikely” that this specimen is from a Homo habilis, but they have not yet assigned the new fossil to any species—new or known. (Another possibility is Homo rudolfensis, but there’s just not enough of the new fossil preserved to be able to confidently put it into this species, either.)

So does this jaw bone force us to redraw the tree of human evolution? No. Does it fill in all the missing gaps? No. Does it answer all our questions and give us definitive proof that we are right about everything? No. (See Eric Meikle and Andrew J. Petto’s “Fossils that Change Everything We Know About Human Evolution (… Or Not)” for some complaints about and correctives to the idea that new fossil discoveries revolutionize our understanding of the broad outlines of human evolution.) But should you talk about it in your classes? Yes!

In my post on whether evolution can stop, I encouraged teachers to bring human evolution into the classroom, since doing so can cause festering misconceptions to bubble up, thus offering marvelous teachable moments. Bringing in a new fossil discovery can not only let you talk about human evolution but also lets you talk about the excitement of ongoing discovery and how evidence is used to test ideas. You could pose questions to students like, “What kind of fossil find would have not supported the hypothesis that Homo evolved from Australopithecus?” or “How is it that we can know so much just from a few bones?” Better yet, you can take your students on a virtual field trip to the Smithsonian’s Human Origins exhibit and explore the 3-D collection of hominid fossils, see scientific reconstructions of the different species, and view the interactive timeline.

Whether or not human evolution is an explicit part of your curriculum, I guarantee that engaging your students in the topic—even just for a day or two—will deepen their, and your, understanding and appreciation of evolution and our own complex and rich prehistory.

Have an idea for a future Misconception Monday or other post? See some good or bad examples of science communication lately? Drop me an email or shoot me a tweet <at>keeps3.