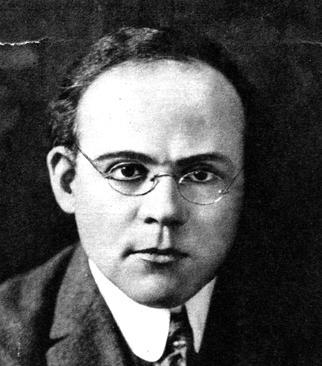

In Evolution in the Courtroom: A Reference Guide (2002), Randy Moore lists, among the colorful characters to flock to Dayton, Tennessee, for the Scopes trial, a fellow by the name of Elmer Chubb, who “claimed that he could ‘withstand the bite of any venomous serpent.’” Unfortunately, as I explained in part 1, although Chubb’s presence was advertised on a handbill which featured a testimonial from William Jennings Bryan and a testimonial—or, better, antitestimonial—from H. L. Mencken, Chubb wasn’t present in Dayton, for the simple reason that he didn’t exist: he was the satirical creation of the poet Edgar Lee Masters (seen here). “Dr. Chubb was most likely to come to life when Masters was bored, tired, tense, or in the mood to play the buffoon,” according to Herbert K. Russell’s Edgar Lee Masters: A Biography (2005). But Masters wasn’t present in Dayton, either. So where did the handbills advertising Chubb come from?

The clue is provided by Mencken’s (anti-)testimonial. “Chubb is a fake,” Mencken was quoted as saying. Whether or not he was right in boasting, “I can mix a cyanide cocktail that will make him turn up his toes in thirty seconds,” he was right that Chubb was a fake. In “Inquisition,” published as a chapter of his memoir Heathen Days (1943), Mencken explains that Masters offered to prepare a handbill from “one of his favorite stooges,” i.e. Chubb, for him to distribute in Dayton. Mencken had a thousand copies printed, and hired a couple of local boys to distribute them in Dayton. And what was the upshot? “Precisely nothing turned up. Hundreds of copies of the circulars were flying about the grass, and dozens of yokels had them in their hands, but no one showed any interest in Dr. Elmer Chubb.” Mencken’s explanation was that “the miracles he offered were old stuff in upland Tennessee.”

He doubtless had in mind the Holy Rollers, a sometimes pejorative term for members of Protestant sects whose worship is “characterized by frenzied excitement or trances,” as the Oxford English Dictionary puts it. Famously, Mencken filed a report from Dayton on July 13, 1925, relating his excursion to the hills outside Dayton to view a Holy Roller service at which there was speaking in tongues (“He leaped into the air, threw back his head and began to gargle as if with a mouthful of BB shot. Then he loosened one tremendous stentorian sentence in the tongues and collapsed”) if not actual snake-handling and poison-drinking. (It should be noted that snake-handling is a genuine, if increasingly rare, religious practice. In 2013, Time magazine reported, “There are about 125 snake-handling churches in the United States.”) When Mencken’s report reached the Sun, his editor tacked his report to a bulletin board and pronounced, “That’s reporting.”

It wasn’t, not exactly. Gripping as Mencken’s report was, it was clearly slanted and exaggerated, and not clearly typical of religion in upland Tennessee. Marion Elizabeth Rodgers notes in her Mencken: The American Iconoclast (2005), “In an effort to prove to Mencken and the other journalists that their reporting was biased, that within those same hills there also existed educated circuit preachers, drugstore owner Fred Robinson [in whose store the idea of the Scopes trial was hatched] made a special effort to introduce out-of-state reporters to a highly educated minister. The New York Times subsequently wrote in amazement of the Tennessee mountain man who had, along with his old clothes and polished boots, a scholar’s knowledge of Greek and Hebrew as well as Darwin’s Origin of Species. But to Robinson’s dismay, ‘Mencken kept with the hillbilly story of the Holy Rollers.’” But, not for the first time, I digress.

Anyhow, assuming that Moore wasn’t intentionally perpetuating Mencken and Masters’s hoax (and that he and Mark D. Decker weren’t doing so in their More than Darwin [2008], which contains a similar reference to Chubb), what accounts for the mistaken inclusion of Chubb? Discussing Masters’s and Mencken’s hoax in “Two Stories of the Scopes Trial” (2009), Lawrence M. Bernabo and Celeste Michelle Condit comment, “only the Commonweal bit.” I haven’t been able to look at its contemporary coverage, but the Commonweal’s editor Michael Williams summarized the handbill without describing it as a hoax in his Catholicism and the Modern Mind (1928), adding, amusingly, “An irreverent newspaper worker, who had experimented, said he would bring a drink of local corn whisky to Dr. Chubb, if cyanide of potassium did not work, knowing that if Dr. Chubb took a real drink it would be all over with the miracle worker.”

Yet my guess is that Moore found Chubb not in the Commonweal but in Norman D. Furniss’s The Fundamentalist Controversy, 1918–1931 (1954), which offers a list of zanies who had rolled into town to take advantage of the opportunity for publicity: “Lewis Levi Johnson Marshall, ‘Absolute Ruler of the Entire World, without Military, Naval, or other Physical Force’; Elmer Chubb, who could withstand the bite of any venomous serpent; Wilb[u]r Glenn Voliva, exponent of the flat-earth school of geography, and many others came to Dayton to peddle their especial anodynes.” Williams also mentioned Marshall, Chubb, and Voliva, in that order and in the space of two paragraphs, but Furniss mentioned them all in that order and in the same sentence, and also misspelled “Wilbur” as “Wilber,” just as Moore did. But Furniss cites Williams in the same chapter of his book, so it’s very possible that Williams was the original journalist who was Chubbed.