I will never forget one day in spring 1974 when my father returned home from a trip to Xenia, Ohio. Dad was in the insurance business, and I was used to hearing cautionary tales about people who injured themselves while setting off home fireworks, riding motorcycles without helmets, or cleaning out their gutters while standing on rickety ladders. But this was different. Dad heard about a lot of destruction in his line of work, but what he saw in Xenia left him practically speechless. The entire downtown was destroyed, and 33 people had been killed. It was by far the worst disaster he’d ever personally witnessed, or ever would again.

The tornado that struck Xenia on April 3, 1974, was part of what came to be called the 1974 Super Outbreak. At least 148 tornadoes were confirmed across 13 U.S. states and one Canadian province. Thirty of those tornadoes were level EF4 (winds of 267 to 322 kilometers per hour [kph]) or EF5 (winds of more than 322 kph). The total death toll was 319. For 37 years, the 1974 Super Outbreak held the record of most tornadoes in a single 24-hour period, until the 2011 Super Outbreak, which involved an astonishing 360 confirmed tornadoes, 15 of which were EF4 or EF5 in strength. Since 2011, two more super outbreaks have occurred, one each in 2020 and 2021, each containing more than 100 tornadoes within a 24-hour period.

The tornado that struck Xenia on April 3, 1974, was part of what came to be called the 1974 Super Outbreak. At least 148 tornadoes were confirmed across 13 U.S. states and one Canadian province. Thirty of those tornadoes were level EF4 (winds of 267 to 322 kilometers per hour [kph]) or EF5 (winds of more than 322 kph). The total death toll was 319. For 37 years, the 1974 Super Outbreak held the record of most tornadoes in a single 24-hour period, until the 2011 Super Outbreak, which involved an astonishing 360 confirmed tornadoes, 15 of which were EF4 or EF5 in strength. Since 2011, two more super outbreaks have occurred, one each in 2020 and 2021, each containing more than 100 tornadoes within a 24-hour period.

Hmmm. Three super outbreaks in 11 years, after a 37-year gap? Does that mean climate change is making tornadoes worse? That sounds like a question for science!

And it is! But it turns out that it is not a straightforward question to answer. And one reason is that you might choose from a lot of different parameters to assess whether one tornado, or one tornado season, is worse than another. Do you measure the number of tornadoes, in which case the Super Outbreaks are the worst events? Or do you measure the number of deaths? Or the amount of economic damage? Or wind speed, atmospheric pressure, or length of time on the ground? Depending on which of these measures you choose, you might get different answers to your question of whether tornado activity is growing worse over time in a way that points to climate change as a contributing factor.

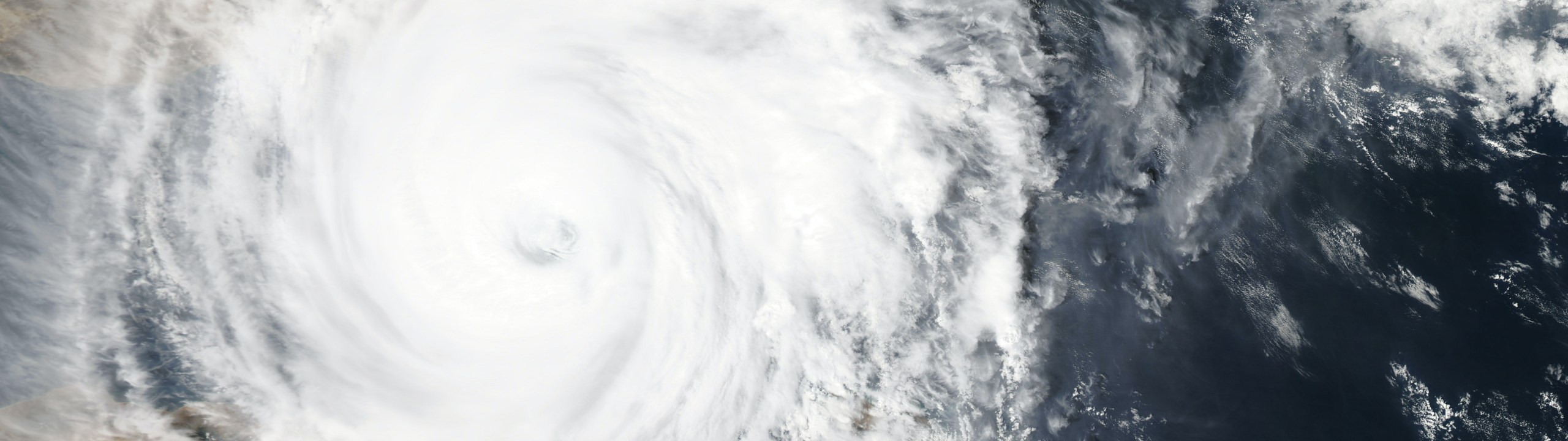

You could do a similar exercise with hurricanes, tornadoes’ larger equatorial cousins. Is climate change making hurricanes worse? Well, that depends on whether you define worse in terms of the number of hurricanes, their size or their intensity, their destructiveness of lives or property, the amount of rainfall they bring, the distance they travel over land, the amount of time they spend over any given place—well, you get the picture. As if those weren’t enough possible choices, sometimes new parameters present themselves. For example, several recent hurricanes have intensified with unexpected quickness; can that characteristic be linked to climate change?

The interaction of climate change with extreme weather is complicated and probabilistic (by which I mean that the best you can do is give a probability range for the impact of climate change, not a “yes” or “no”), and that makes the topic particularly amenable to bad faith arguments and misconceptions. Those who aim to downplay climate change, or discourage policies that would reduce fossil fuel use, will often emphasize that many uncertainties remain about how climate change affects different kinds of extreme events. And, yes, there are uncertainties. But that doesn’t mean we don’t know anything at all. This Heritage Foundation interview with one of its own economists is an excellent example of traveling in a more or less straight line from uncertainties about the impacts of climate change on hurricanes to the conclusion that reducing carbon emissions would do more harm than good. (Teachers, if you discuss this interview with your students, be prepared to help them examine the rhetorical devices the economist uses to reach his conclusions. The National Center for Science Education (NCSE) uses the FLICC [Fake Experts, Logical Fallacies, Impossible Expectations, Conspiracy Theories, Cherry Picking] model developed by John Cook to inoculate students against potentially deceptive argumentation.)