When we got the results back from our national survey of climate change education, the good news jumped out at us. Climate change is actually showing up in schools.

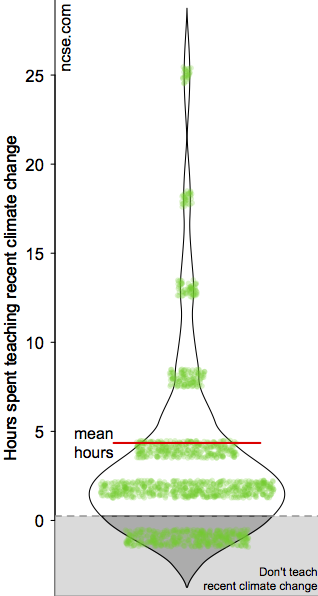

1500 teachers' responses when asked how much time they allocate to climate change. Widths of the green bars correspond to the relative frequency of each response, and the black lines are a smoothed estimate. Three quarters of teachers spend at least an hour on climate change.

1500 teachers' responses when asked how much time they allocate to climate change. Widths of the green bars correspond to the relative frequency of each response, and the black lines are a smoothed estimate. Three quarters of teachers spend at least an hour on climate change.We asked teachers how much time they devote to a range of subjects in their classrooms, including recent climate change (within the last 150 years), asking them to pick between not covered, 1-2 hours, 3-5, 6-10, 11-15, 16-20, and >20. The most common answer for climate change was 1-2 hours.That’s also the median answer, with half of teachers answering above it and half below. Among teachers who say they cover this topic, they average almost 5 hours of class time. But that value is driven largely by the small number of teachers who devote weeks and weeks to the subject. In the graph to the right, you can see that long, thin line of exceptional teachers embracing climate change education. (The black line is a smoothed version of the green scatterplot, and the widths of the green blocks are proportionate to the number of responses in each category—a bar graph.)

That wasn’t the result we predicted. Our fear in preparing the survey was that almost no teachers would be covering climate change at all. To counter that, we designed the survey to ensure that we had a reasonable sample of earth science teachers. While many districts don’t even offer an earth science course, we figured that if we wanted to find teachers covering climate change, they’d be the ones to ask. On the other hand, we expected that high school chemistry and physics teachers were unlikely to be covering climate change, despite the topic’s obvious relevance in such classes, but included them in the survey in hopes that they’d surprise us.

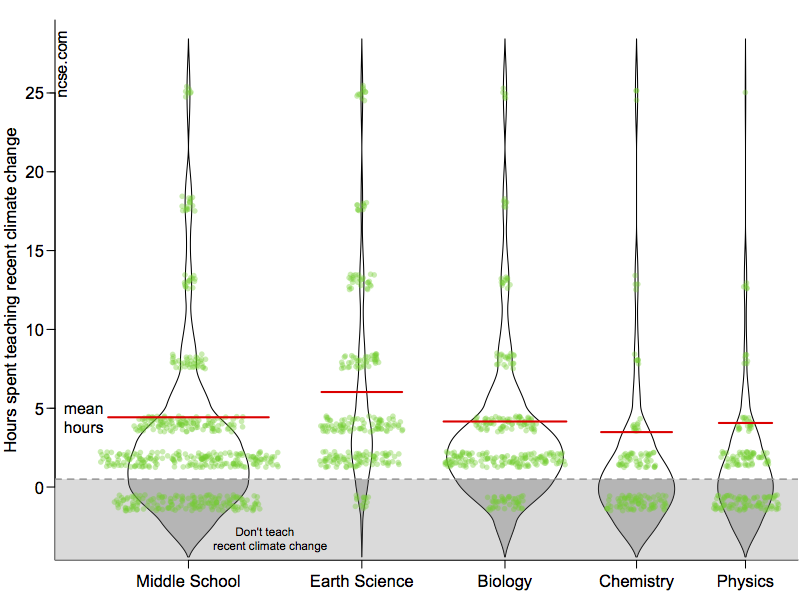

Teachers' responses when asked how much time they allocate to climate change. Widths of the green bars correspond to the relative frequency of each response, and the black lines are a smoothed estimate, with their widths scaled to the true frequencies of each group of teachers in the US at large.

Teachers' responses when asked how much time they allocate to climate change. Widths of the green bars correspond to the relative frequency of each response, and the black lines are a smoothed estimate, with their widths scaled to the true frequencies of each group of teachers in the US at large.To see how our pessimistic predictions fared, we can separate out each subject area. I scaled the widths of the black lines in this graph to match the relative frequency of each group in the public school teaching workforce, while the widths of the green bars still correspond to the relative frequency of each response in our survey. You can see how we oversampled earth science teachers and somewhat undersampled physical science teachers.

As we expected, earth science teachers are by far the most likely to teach climate change, and were the only group where the median teacher spent 3-4 hours on the topic rather than 1-2. Encouragingly, relatively few biology teachers said they didn’t cover climate change at all. Three quarters of middle school teachers say they also cover the topic.

Nearly every student takes middle school science, and almost as many take a high school biology class. Even among physics and chemistry teachers, who we feared might not teach it at all, about half are teaching about climate change.

That’s the good news, and it’s important. Since NCSE started working on climate change, we’ve worried that the greatest challenge to climate education was simply that teachers were skipping the subject. Getting a subject into curricula is a big threshold to cross. This survey shows that the teachers have already crossed that threshold.

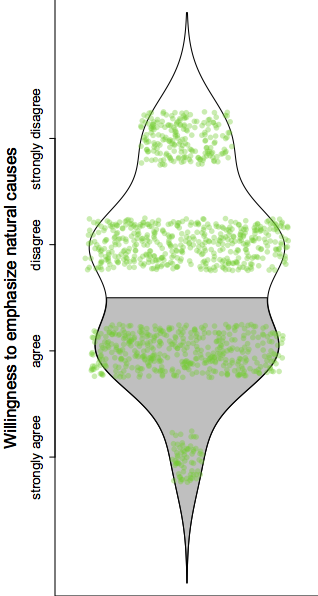

Teachers' responses when asked if they emphasize that modern climate change is driven by natural causes.

Teachers' responses when asked if they emphasize that modern climate change is driven by natural causes.But there’s another big challenge still before us. Climate science is in the classrooms, but that doesn’t mean students are being taught what climate scientists understand.

Asked whether their climate change lessons “emphasize that many scientists believe that recent increases in temperature are likely due to natural causes,” one in three teachers agreed with the statement. There’s virtually no scientific literature making such a claim, and surveys of scientists indicate that fewer than 3 in 100 would endorse it. While far more teachers indicate (on a separate question) that they emphasize the consensus that humans are primarily responsible for modern climate change (about two thirds), many teachers either present only the contrary view (about one in twelve teachers), or say that they teach both ideas (one in four). That mix of contradictory claims can only serve to confuse students.

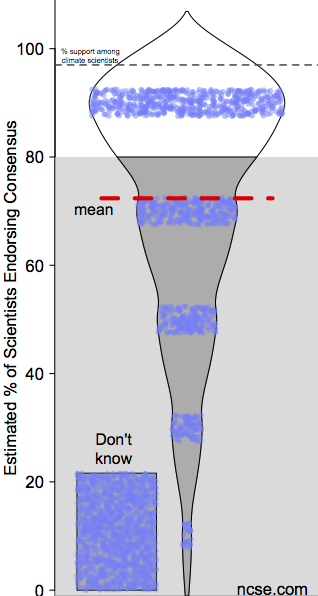

Teachers' responses when asked what percentage of scientists agree that climate change is caused by humans.

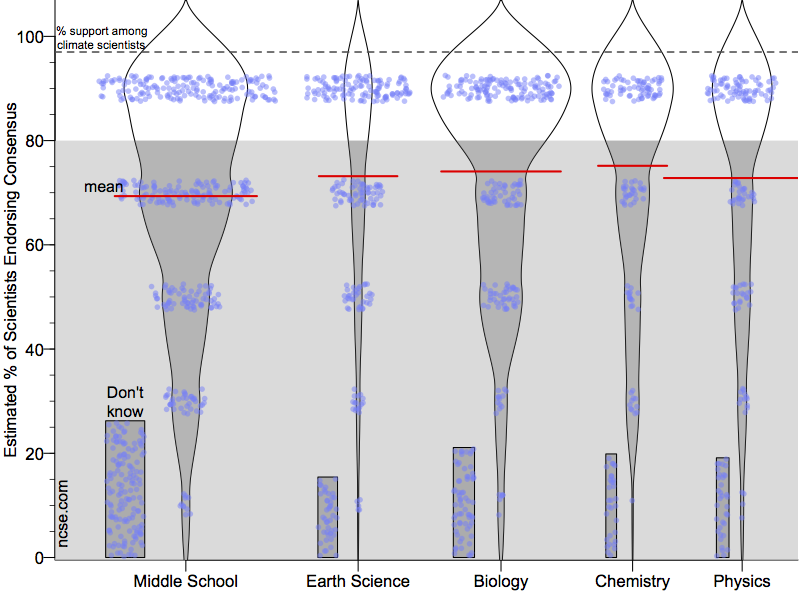

Teachers' responses when asked what percentage of scientists agree that climate change is caused by humans.Why would teachers give so much emphasis to a idea with no scientific merit? Is it political: an intentional effort to undermine the science? Looking at another question from the survey, it's clear that the problem is that teachers have been misled. Asked “To the best of your knowledge, what proportion of climate scientists think that global warming is caused mostly by human activities?,” teachers notably underestimated the consensus. Fewer than half correctly estimated the consensus at over 80%. One in five simply chose “I don’t know.”

As we might expect, earth science teachers were the least likely to select “I don’t know.” By contrast, over a quarter of the middle school teachers said they didn’t know (or left the question blank). Middle school teachers also greatly underestimated how many scientists agree that modern climate change is caused by humans. Given that there are far more middle school science teachers than earth science teachers, and that middle school teachers reach far more students, this misperception of the science is worrisome.

Teachers estimates of the extent of scientific consensus, broken down according to the subject they teach. Widths of the smoothed black lines correspond to the relative frequency of each subject in the national teaching workforce. Heights of the "don't know" bars correspond to the frequency of that response.

Teachers estimates of the extent of scientific consensus, broken down according to the subject they teach. Widths of the smoothed black lines correspond to the relative frequency of each subject in the national teaching workforce. Heights of the "don't know" bars correspond to the frequency of that response.If teachers don’t appreciate how much scientific support climate change has, why would we expect them to teach it as a topic on which scientists agree? If they think the scientific consensus is not widely-supported, why wouldn’t they want to include countervailing views? And if the teachers don’t appreciate the depth of scientific consensus, how can we expect them to guide their students to appreciate this essential context?

There are several possible culprits for this misperception. The first is time itself. The median US teacher is 41 years old, meaning half of the teachers would have graduated college before about 1995. That means they finished their formal education before groups like the IPCC were prepared to confidently attribute climate change to human activities. Unless teachers have been keeping up with the science on their own, or have gotten climate science training as part of their professional development, they could still be carrying those outdated ideas with them. While teachers could (and many do) seek out updated science education, there are few sources routinely provided to teachers on this and other developing topics of scientific interest.

The second culprit is the lack of readily-available continuing education for teachers—and the relative absence of climate science in science textbooks and other resources. Until the last few years, climate science was largely absent from state science standards, meaning it hardly turned up in textbooks or continuing education courses. The Next Generation Science Standards give climate change new prominence, and textbooks and trainings will surely begin to reflect that change soon. But until that push, teachers weren’t getting a clear message about the growth of the consensus. Even now, states and districts that have adopted standards which include climate science often provide little additional content training, if any. In large part, teachers have to fend for themselves.

Which brings us to the third culprit: the climate change denial movement. Every year, NCSE hears reports from teachers being mailed climate change denial propaganda from groups such as the Heartland Institute. Sometimes these are videos that they can show in class, others are slick sciencey-looking reports meant to cast doubt on the science. And if teachers try to find sources online, or vet those mailings with a quick Google search, they are likely to encounter copious denialist misinformation. Even if they succeed in identifying and rejecting the misinformation, the wealth of competing claims can make it seem as if the science behind climate change is in genuine dispute. The denialist strategy has always held that “doubt is our product,” and teachers’ self-reported underestimation of the scientific consensus is a measure of that strategy’s success.

A final culprit is teachers’ experiences outside the classroom. What teachers hear from other parents as they watch their children play soccer, or as they wait in line at the store affects how they teach, as does what they hear on local talk radio, read in the papers, and pick up in conversations after church. If they live in a community where climate change is controversial, it’s understandable that they would incorporate the community’s doubts into their teaching. In the survey, few teachers reported any overt pressure not to teach climate change, but the subtle pressure of everyday experience can be far more powerful than an overt challenge.

All of us live near teachers, and that means we can all help relieve the pressure they experience. A polite, friendly conversation can do wonders to give teachers confidence in how they teach climate change. You might even use the news coverage of this survey to start that conversation, and help change the climate in your local schools by ensuring teachers know their community supports climate education.

Taking on the culprits of denial requires us to work together. That's why NCSE was founded over 30 years ago, and it still motivates our work today. By signing up as a member, you won’t just give us the resources to continue our work (including more surveys), it’ll ensure that you get alerts when textbooks are under attack, and when there’s a chance to bring climate change into your state’s science standards. We’ll do the legwork to find ways to root out science denial, we’ll talk to teachers and find out what they want and need, and we’ll figure out how to get teachers resources to stay on top of new science. But we’ll need you to join your voice with ours if we’re going to make these important changes.