Wouldn’t it be great if you could measurably increase teenagers’ understanding of climate change in just one hour? Well, it turns out you can. A study conducted by researchers at Stanford, Yale, and George Mason Universities, found a single hour-long assembly had the following impact:

Wouldn’t it be great if you could measurably increase teenagers’ understanding of climate change in just one hour? Well, it turns out you can. A study conducted by researchers at Stanford, Yale, and George Mason Universities, found a single hour-long assembly had the following impact:

* Students demonstrated a 27% increase in climate science knowledge.

* More than one-third of students (38%) became more engaged on the issue of climate change.

* The number of students who talked to parents or peers about climate change more than doubled.

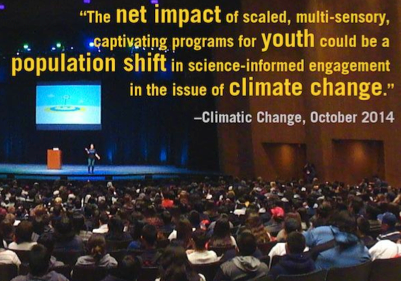

The assemblies, specifically calibrated with high school students in mind, are the work of ACE, the Alliance for Climate Education. The just released study in the prestigious journal Climatic Change details how ACE's hybrid of education-entertainment successfully informs students about the reality and challenges of climate change, and inspires them to think about and act upon its implications in their everyday lives.

Full disclosure. We’re big fans of ACE here at NCSE. ACE is based in Oakland, California and I’ve known their current Executive Director (and new father) Matt Lappé since shortly after ACE was formed some five years ago. ACE's founder, Mike Haas, is the newest member of our board, and we have collaborated in a variety of ways over recent years.

These findings are impressive, no doubt, but consider the context: many if not most students currently learn little or nothing about climate change in school. One hour barely scratches the surface of what they will need to know in order to understand the risks and range of responses to climate change. Clearly, ACE's approach can and should be scaled up to help students gain a baseline understanding of climate and energy issues that can be built on through more in-depth curriculum.

Another study in the same journal entitled "Overcoming skepticism with education: interacting influences of worldview and climate change knowledge on perceived climate change risk among adolescents” by Kathryn Stevenson and colleagues, also suggests that teaching kids about the science behind climate change increases their recognition that climate change is a genuine risk. (Both articles, which are behind paywalls, are summarized by Chris Mooney on his Washington Post blog.) Focused on middle school students in North Carolina, where climate change is only tangentially covered in the state science standards, the authors write:

Overall, students in our study displayed low levels of climate change knowledge, similar to those reported in a national survey of teens (Leiserowitz et al. 2011). Almost 20 % of teens in our study and 46 % of teens in the national survey...either thought global warming was not happening or did not know if it was happening.

So, why is this news? It seems purely intuitive that as students learn more about what scientists know about human impacts on climate, they would come to accept that climate change is real. However, there is a lively debate in the scientific community about whether a person's “belief” in climate change is grounded in their knowledge of the science, or simply a reflection of their cultural and ideological identities.

To put it simply, Dan Kahan's Cultural Cognition research suggests that knowing whether someone is a liberal or a conservative is a better predictor of how they feel about climate change than their level of scientific knowledge.

This seems to be true of adults, but Stevenson’s study examined middle school students, whose worldview may be more evolving, less rigid than adults’. By having students rate themselves on an individualist to communitarian axis used by Kahan and others, she found that the students’ worldview did come into play. She found that communitarians started out with more knowledge and more acceptance of climate change than individualists. But overall acceptance was high.

Communitarians who had low knowledge had about 80% acceptance and those with high knowledge about 90%. For the individualists with low knowledge, there was 55% acceptance of climate change while those with high knowledge accepted the reality of climate change at a rate of about 80%. The surprising finding? Among middle school students, more knowledge has an even greater impact on acceptance among individualists than communitarians.

Suggesting that teens’ worldview hasn’t yet solidified into rigid ideology, the authors write: “Without education specific to climate change, adults may be unable to “connect the dots” provided through general science education.”

In reporting on these studies, Chris Mooney concludes that climate education seems to work “after all”. For those of us who live and breathe climate education, the results of the ACE and Stevenson study are consistent with what we’ve seen in practice: those who know more are more concerned about climate change and take it more seriously than those who know less.

One thing that neither of these studies addresses, but that we at NCSE suspect might be an important issue, is how students’ knowledge of climate science and acceptance of climate change is affected when teachers inappropriately teach climate change as a scientific controversy. If solid scientific instruction can't overcome entrenched identities, how much more destructive might an approach be that presents the science as “debatable”?

We will soon have a much clearer picture of whether and how climate change is being taught, and how often it is presented as scientifically controversial, when we get the results early next year from a survey currently being deployed to middle and high school science teachers across the country. Stay tuned!