Have you heard the joke about the museum guide who, when asked about the sign explaining that dinosaurs became extinct 65,000,004 years ago, replied, “When we put up the exhibit, the experts told us that dinosaurs had been extinct for 65,000,000 years. That was four years ago!”

Have you heard the joke about the museum guide who, when asked about the sign explaining that dinosaurs became extinct 65,000,004 years ago, replied, “When we put up the exhibit, the experts told us that dinosaurs had been extinct for 65,000,000 years. That was four years ago!”

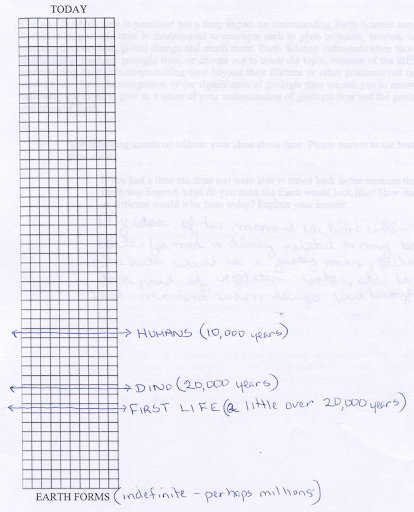

Pretty silly, I know, but it’s no joke that people are really not very good at understanding vast stretches of time. In fact, maybe you’d be willing to test yourself before you read further. On a piece of paper, draw a long, vertical line. This is your Earth timeline. Label the bottom of the line with your best estimate of the age of the Earth. Proceeding upward, add the following events at the approximate time they happened: emergence of life, arrival of the dinosaurs, disappearance of four-legged dinosaurs, and appearance of humans.

Go ahead. I’ll wait.

Research looking at how well people grasp the history of the Earth suggests that you are not alone if your timeline looked something like this:

Wild inaccuracy is rather more the rule than the exception, so don’t feel bad if your timeline is way off. One study of college students found that only 9% of U.S. college students placed the earliest emergence of life between three and 3.5 billion years ago, which was considered correct at the time of the survey—current estimates have pushed that time back to at least 3.8 billion years ago. And a study of middle and high school teachers found that while 16 out of 17 teachers placed the events in the correct order, only seven correctly placed the earliest emergence of life and only one (!) knew when (non-avian) dinosaurs became extinct.

Here’s the correct answer:

So this might come off as a bit of a gotcha exercise. I mean, really, how important is it to remember these dates? Maybe it will surprise you to hear that I don’t care that much about remembering the exact dates. But I do care that we have a general picture in our heads of some basic concepts like how long the Earth has been around compared to when dinosaurs emerged and how long dinosaurs dominated the Earth compared to how long humans have dominated. Why? Because it’s very hard to genuinely understand and appreciate the process of evolution without having a genuine appreciation of How Long It’s Been Going On. And it’s also very hard to appreciate the gravity of recent anthropogenic climate change without realizing that 150 years (roughly the length of time humans have been burning fossil fuels and pumping carbon dioxide into the atmosphere) is not even the blink of an eye compared to the age of the Earth.

When you’re trying to correct an incorrect belief based on a misconception, you need to replace that sticky misconception with a stickier fact. (This is one of the overarching principles of debunking to be found in The Debunking Handbook, by Stephan Lewandowski, John Cook and others, a guide to protecting people from disinformation or correcting people’s misunderstandings if you’re too late to keep them from accepting the disinformation in the first place.) In the case of misconceptions grounded in humans’ inability to genuinely understand vast stretches of time—that is, rooted more in the tendencies of the human brain than in deliberate misdirection (like suggesting that no models can be trusted because all models display some level of uncertainty) or reinforced by sloppy language (like casually describing viruses as agents with feelings)—displacing the misconception requires describing the phenomena in a way that humans intuitively understand.

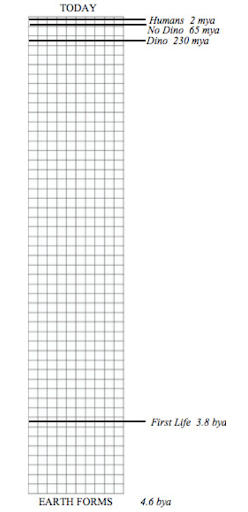

There are some great examples of ways to compare the long history of the Earth to everyday concepts that humans can relate to. For example, here is a clock that shows when the major events of the evolution of life on Earth would have occurred if deep time is compared to a 12-hour span. Life emerges around 2 o’clock but humans don’t appear until just one second before noon.

And here is an animation that shows when major events in Earth history would have occurred in a 24-hour day.

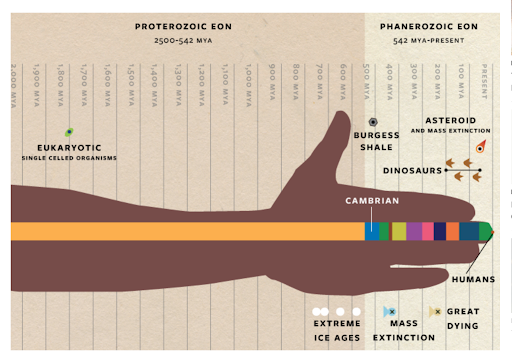

The comparison that I find stickiest is one that places the history of the Earth along the length of a human’s outstretched arm. If your armpit represents 4.5 billion years ago, when the Earth formed, and the tip of your middle finger represents the present, when do you think humans emerged? The answer is “so far along the middle finger of your right hand that if you lightly filed the nail on that finger, you’d file away all of the time since humans evolved.” Here’s a great graphic (from this article by Brooke Borel, illustrated by Katie Scott) that captures this idea well.

I love this illustration, but I wish they’d included the whole arm span. Why? Because, again, the human brain isn’t very good at intuiting the rest of the timeline. There are a lot of examples of graphics and videos that tend to reinforce our natural misconceptions about time rather than replacing them with a more accurate and stickier mental image.

Here is just one example. In this otherwise amazing 90-minute National Geographic film The History of Earth, there are some transitions that made me bang my head against my keyboard. The dramatic formation of the Earth occupies the first 15 minutes of the film. At 15:45, the first single-celled life emerges. So far, the amount of time that has passed in the film is quite proportional to the actual history — about 15% of the history of the Earth in about 15% of the film’s length. But then the narrator says this: “For hundreds of millions of years, nothing happens.” Suddenly, we’re at 3.5 billion years ago learning about the emergence of stromatolites, mounds created by photosynthesizing cyanobacteria using sunlight and carbon dioxide to create sugars and oxygen. Aside from the obvious observation that something must have happened during the 300 million years we skipped over (um, bacteria evolved the ability to photosynthesize — pretty dang important), the condensation of 300 million years into a few seconds feeds right into our human tendency to distribute significant events evenly across all of Earth’s history rather than remembering that most of the events we most care about have happened extremely recently. But wait. It gets worse. After a few minutes spent explaining that the production of oxygen by cyanobacteria will transform the atmosphere and make possible the evolution of multicellular life, at minute 19:29, the narrator informs us that nothing happens for another two billion years! Just a bunch of cyanobacteria, pumping out oxygen! Thanks, cyanobacteria!

Why does this make me crazy? Well, mostly because it’s absurd to suggest that nothing was happening when single-celled microbes were evolving like all get-out, not only becoming capable of photosynthesis but also evolving a huge variety of other genetic tools that would later serve as the building blocks for the genomes of more complex, multicellular organisms. Discounting two billion years of microbial evolution — almost half of the entire history of the Earth — as a time when nothing was happening is not a good way to set the stage for anyone to realize just how long our evolutionary history actually is. (Nor is it a good way to help us appreciate the extreme bad-assery of microbes.)

But back to the film. Twenty-four minutes into The History of Life, we reach 650 million years ago. The last 75% of the film is spent describing just 14% of Earth’s history.

Don’t think that I don’t get it. I get it. It would be a pretty boring film if it spent 40 minutes saying over and over again, “During this time, bacterial life is evolving in complex ways that we cannot see because bacteria don’t leave fossils. Maybe there were some big extinctions. But they didn’t leave a geologic trace. We just don’t know exactly what was happening, but something was.” And then condensing the entire history of multicellular life into the last 12 minutes of the film, with humans flickering on screen in the last few seconds. I see the problem, I really do.

Still. It’s no wonder that our failure to understand deep time lingers on.