In part 1 of this Q&A, I asked John Mead, a Dallas teacher who befriended Lee Berger, the discoverer of Homo naledi, about how he came to know about the new hominid species in advance, and he answered in detail. Now I’ve got a simple request for him…

Stephanie Keep: Sum up the importance of Homo naledi in one sentence.

John Mead: Besides the discovery of a fascinating new species of hominin, H. naledi offers us a unique look at a well-defined population of hominins as opposed to defining a new species based on a few fossil fragments. [Fossils from at least fifteen hominins were discovered in the same locale.]

SK: What did you tell your students about Homo naledi? What questions did they have?

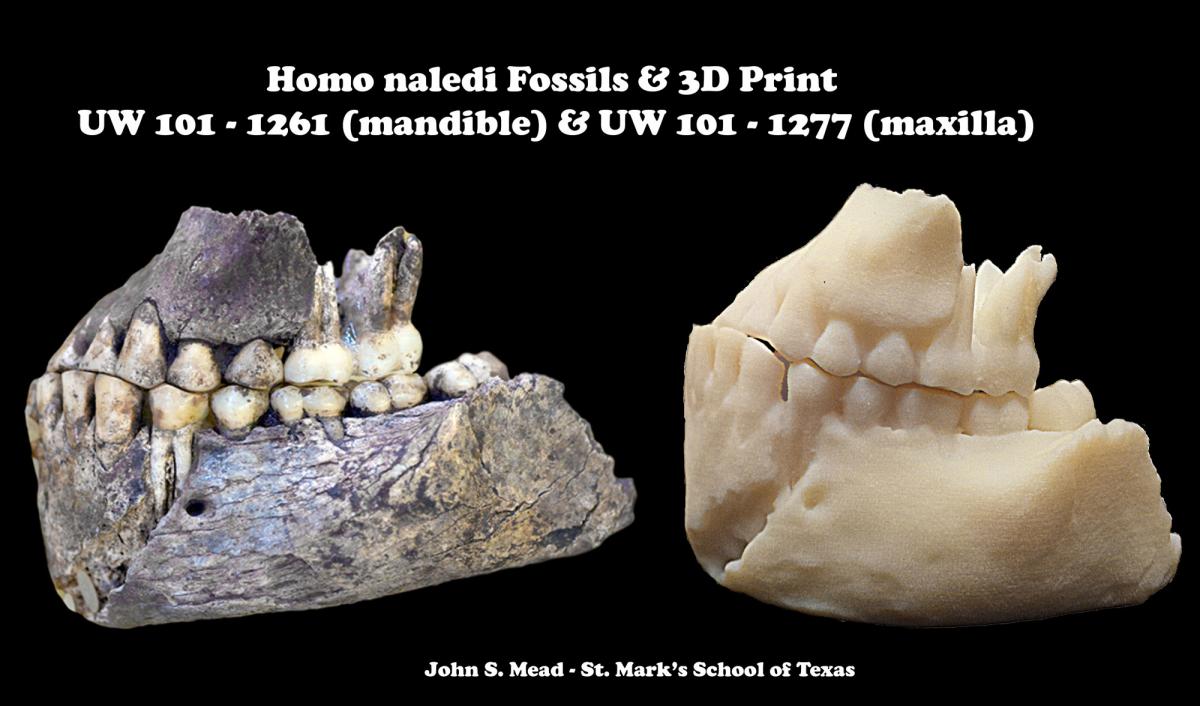

JM: I have been teaching about this project since November 2013, but the details were not made public until September 2015. So mostly what I was telling my students about what we knew had come up from the fossil chamber. This was not detailed, so it was more about the excitement of discovery at first. By the time of Dr. Berger’s November 2014 visit to Dallas, we had seen some photos of some of the fossils, and my middle schoolers were able to begin hypothesizing about what they thought these  fossils might represent. Given we had no dates and only glimpses of the fossils, it was a valuable lesson in looking ahead to what sort of evidence my students wish they had access to. Now that the H. naledi data is available, this year’s group of students has the chance to compare the fossils (some of which I just 3D-printed a few hours ago) to other species and wrestle with the claims of the H. naledi team and its critics.

fossils might represent. Given we had no dates and only glimpses of the fossils, it was a valuable lesson in looking ahead to what sort of evidence my students wish they had access to. Now that the H. naledi data is available, this year’s group of students has the chance to compare the fossils (some of which I just 3D-printed a few hours ago) to other species and wrestle with the claims of the H. naledi team and its critics.

SK: What do you personally find to be the most remarkable part of this discovery?

JM: From the paleoanthropological point of view, I was floored both by the unique nature of H. naledi’s anatomy but even more so by the realization that the fossil chamber was so clean (no other fossil creatures save a modern owl). This of course helped lead to the hypothesis of ritual body disposal by H. naledi.

More personally, I was impressed that I—as a secondary school biology teacher—was welcomed as a member of the team and treated with utmost professional respect, especially since paleoanthropology has not historically been known to be open to “outsiders” (non-senior scientists). In my opinion, this team was so successful because it was open to a range of folks whose skillsets were welcomed and used to get the best out of all involved.

More personally, I was impressed that I—as a secondary school biology teacher—was welcomed as a member of the team and treated with utmost professional respect, especially since paleoanthropology has not historically been known to be open to “outsiders” (non-senior scientists). In my opinion, this team was so successful because it was open to a range of folks whose skillsets were welcomed and used to get the best out of all involved.

SK: How long did you have to keep Homo naledi a secret? Was it difficult?

JM: I first heard details about H. naledi that I could not share in the spring of 2015. These details were under embargo until the announcement on September 10, 2015. As a teacher, I am used to sharing information eagerly, so this was a genuine challenge for me. I felt particularly bad when I returned from South Africa in late July 2015, and my colleagues and students knew I had embargoed information. I was able to share lots of my experiences, but I always felt bad when I had to say, “The answer to that question will have to wait till the announcement.” Giving such responses is simply not a part of my DNA.

SK: One of my critiques of the new NGSS standards is that human evolution is not mentioned at all. Do you think that’s a problem?

JM: It’s absolutely a problem. Evolution ties all of biology together and students find it incredibly natural to wonder about human evolution in particular. To ignore it (in fear of controversy perhaps?) also passes up a chance to do a good job of teaching the nature of science in a meaningful way that will stick with students far better than the standard way most of us approach teaching about the scientific method.

JM: It’s absolutely a problem. Evolution ties all of biology together and students find it incredibly natural to wonder about human evolution in particular. To ignore it (in fear of controversy perhaps?) also passes up a chance to do a good job of teaching the nature of science in a meaningful way that will stick with students far better than the standard way most of us approach teaching about the scientific method.

SK: Why do you think it’s important to teach human evolution? Is it always part of your syllabus?

JM: I’ve taught biology for twenty-six years, and I’ve had human evolution in my curriculum since the start. Since I teach mostly middle school students, I know that their worldview tends to center around themselves. Therefore my course focuses on biology as it relates to them as human beings. As such, gaining an understanding how they biologically arrived here is mission-critical to my course. Once they understand human evolution, I can easily jump into topics like the genetics of skin color with even my youngest students in a way that gives them a broad perspective for their age.

SK: What’s your advice to teachers who say that they don’t have room in their curriculum to teach human evolution?

JM: In my younger days, I was genuinely upset that so few teachers taught human evolution, but over the years I have a better sense of why most avoid it. I believe that many are simply uncomfortable with it. They may have a limited background with human evolution and understandably steer away from the controversy they fear it will bring. While a whole unit on human evolution may be a big jump for many, there are ways to weave it into existing topics that may make it possible to talk about it and steer clear of the “I did not come from a monkey” reaction. Topics that naturally allow for “safe” discussions of human evolution can be the genetics of skin color, the evolution of lactose tolerance in modern humans, and the susceptibility/resistance to malaria in certain populations. When we focus more on the genetic aspects of human evolution, it allows students to be more comfortable with the idea and allows for further exploration into deeper hominin history.

SK: One last question: Did you wear an Indiana Jones-style hat while on site in Africa? Be honest.

SK: One last question: Did you wear an Indiana Jones-style hat while on site in Africa? Be honest.

JM: There was no Indiana Jones hat for me in the field—but the attached image indicates my current preference for cephalic fashion!

Are you a teacher and want to tell us about an amazing free resource? Do you have an idea for a Misconception Monday or other type of post? Have a fossil to share? See some good or bad examples of science communication lately? Drop me an email or shoot me a tweet @keeps3.