Let it be known that I love, love, love Tobin Grant’s work at Religion News Service. The political scientist at Southern Illinois University examines the role of religion in politics (and vice versa) using beautiful and informative data visualizations. I’m particularly enamored of this graphic, showing how members of different denominations fall out in terms of belief that the government should provide more services, compared to the degree to which they believe the government should promote morality.

I love it so much, in fact, that I decided to make my own version, exploring church memberships’ views on evolution and other scientific topics.

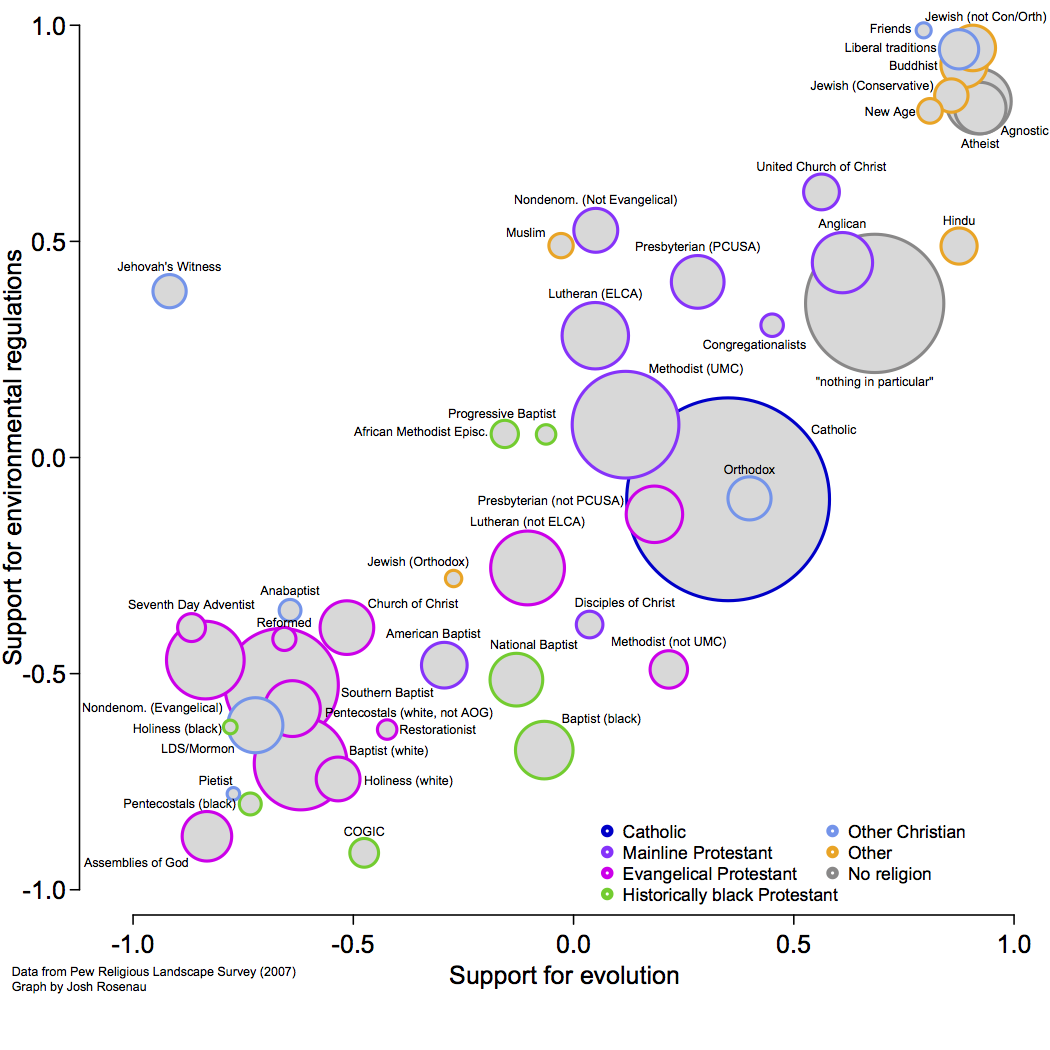

So I downloaded the 2007 version of Pew’s Religious Landscape Survey (a new version of this survey was just published, but the raw data aren’t available, nor have results from any questions on evolution been published), and broke it down the same way Grant did.

I examined two questions. One asked people which of these statements they most agreed with:

I examined two questions. One asked people which of these statements they most agreed with:

Stricter environmental laws and regulations cost too many jobs and hurt the economy; or Stricter environmental laws and regulations are worth the cost

The other question asked people to agree or disagree with the statement:

Evolution is the best explanation for the origins of human life on earth

To get the axes, I standardized the same way Grant did, except I didn’t rescale to the 0-100 scale, since I didn’t want this to seem like a percentage when it isn’t.

The circle sizes are scaled so that their areas are in proportion to the relative population sizes in Pew’s massive sample (nearly 36,000 people!). The circle colors match the groupings in Grant’s graphic, though I used different colors just to be difficult.

In Grant’s version, evangelicals cluster together as advocates for small government in general who nevertheless want government to take a bigger role in promoting morality, while historically black church members cluster together as advocates for greater government action and greater role of government in morality. Mainline Protestants don’t see much role for government on either axis, neither in promoting morality nor in promoting social welfare. The “Nones,” people who don’t identify with any church (even if they believe in God and attend services, as with many of those who told Pew their religion was “nothing in particular”), are secularists, with a wide range of views on the role of government in social welfare, but generally opposing a government role in morality.

Groups’ responses on the two questions I examined were more highly correlated, at least in general. Jehovah’s Witnesses stand out as an outlier, advocating for environmental action while staunchly rejecting evolution (a topic, perhaps, for another day). But mostly, groups that support evolution also support environmental action. And indeed, the groups most likely to support environmental action and evolution are also the least likely to support a role for government in promoting morality (I tried adding that data to the graph above, but it got confusing). By contrast, there was not a clear relationship when I tried to include the question on government social welfare spending; this is surprising in that environmental spending would seem to be a form of social welfare spending, but not surprising in light of Grant’s chart.

So what does this tell us?

First, look at all those groups whose members support evolution. There are way more of them than there are of the creationist groups, and those circles are bigger. We need to get more of the pro-evolution religious out of the closet.

Second, look at all those religious groups whose members support climate change action. Catholics fall a bit below the zero line on average, but I have to suspect that the forthcoming papal encyclical on the environment will shake that up.

Third, the evangelical Creation Care movement had a ways to go in terms of motivating grassroots support, at least in 2007. It’ll be interesting to see how much these results change in the more recent version of the Religious Landscape Survey, after eight years of hard work by those evangelical advocates for environmental stewardship.

Fourth, this chart makes clear that orthodox Jews are more like evangelical Christians than they are like other Jews. Part of the reason Israel is so creationist is because there are lots of orthodox Jews there.

Finally, creationism has a solid hold in African American churches. There’s important outreach to be done on that front, and it’ll have to be accompanied by an acknowledgment of racism in science, both historically and in its current practice. While science is not itself racist, and neither is evolution, both have been tainted by and abused for the benefit of racism, and the African American community has cause for its ambivalence. Those of us who love evolution, love science, and want to share that love with our brothers and sisters of all races and religions need to find better ways to bridge these gaps.

Similarly, there’s a clear need (or was in 2007) to make clearer the connection between social welfare policy and environmental policy. Members of historically black churches support social welfare spending but not environmental policy, yet many advocates for environmental action would consider that a form of social welfare policy. There’s been a lot of work on environmental justice in recent years, building those bridges, so perhaps the results from the 2015 version of the survey will show some change as well.

Update: An earlier version of this image omitted the legend explaining the colors of the circles.