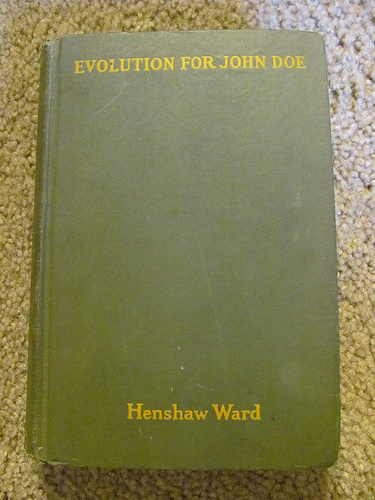

I’m still discussing Henshaw Ward’s Evolution for John Doe (1925), a copy of which I bought over the Labor Day weekend, finding a few of its pages still unopened. In the first chapter, Ward, a teacher of English turned science popularizer, not only lists what he takes to be eight prevalent misconceptions about evolution but also explains how his book attempts to defuse them. I described the book in general in part 1, discussed the first two misconceptions—that “evolution is ‘the doctrine that man is descended from monkeys’” and that “evolution explains the origin of life”—in part 2, and discussed the next three misconceptions—that “evolution has something to do with ‘progress’; that “there is something mystical and awesome about ‘Evolution’”; and that “the theory is materialistic and tends to weaken religious faith”—in part 3. If you find it surprising that I’m going to discuss the final three misconceptions in part 4 now, again describing the misconception, Ward’s approach to it, and whether and if so how today’s popular expositions of evolution approach the misconception, what can I say?

The sixth misconception: “John Doe suspects from head-lines in his newspaper that evolution is a debatable theory, that it is being overthrown every six months, and that it may be discarded before long.” Ward might have been writing today, when Smithsonian magazine is proclaiming that Homo naledi “may change what we know about human evolution,” as if everything were up for grabs. Ward’s solution is just to explain the scientific basis of evolution so clearly that John Doe will come “to understand that evolution is here to stay; there is no more chance that the theory will be disproved than there is that men will some time give up their belief that the earth is round.” That’s the usual solution also of today’s popular expositions of evolution. Indeed, Richard Dawkins’s The Greatest Show on Earth (2009) says that evolution is a “theorum” (his coinage), meaning that it is treated by common sense “as a fact in the same sense as the ‘theory’ that the Earth is round and not flat is a fact.” Short of providing a discussion of media sensationalism in general, it’s hard to know how to improve on the approach.

The seventh misconception: “To the common horse-sense of John Doe evolution appears probable. ‘But,’ he says, ‘it is not to be seen at work here and now, and so it looks dubious to me.’” It isn’t clear what Ward means here, and the remainder of the paragraph—“When he has seen the ‘billion-year movie’ in Chapter XII, he will feel relieved”—isn’t helpful. Turning to the chapter, though, reveals that Ward is thinking of the challenge of understanding deep time. The “billion-year movie” is a hypothetical time-lapse film that collapses a billion years into two hours, 140,000 years into one second. “And man in this picture?” Ward asks. “He was on the globe during the last second or two; civilized man has been here a tenth of a second.” Today’s popular expositions of evolution often ring variations on the theme. In Time’s Arrow, Time’s Cycle (1987), Stephen Jay Gould listed a few, including that of a Swedish correspondent who imagines her pet snail starting at the South Pole during the Cambrian period and steadily oozing toward Malmö—a route that flummoxed Google Maps, by the way (“outside our current coverage area for driving”).

The eighth and final misconception, at long last: “Mr. Doe supposes that evolution is extremely difficult, so that he has small chance of ever finding out about it.” Ward explains, “It is true that most scientific books are highly technical, and evolution is based on several branches at once, and that each is hard to learn about, and that the combination of several in one theory is excessively complicated.” His solution, of course, was “to read a number of the standard works of evolution,” and his book attempts to present a digest of them, “as if I were telling a friend about the knowledge that is so new and imperfect in my mind.” After ninety years of unremitting scientific progress, it’s even harder to acquire a comprehensive understanding of evolution at a professional level. Yet talented expositors of evolution, both working scientists and informed journalists, abound as never before, and have moreover colonized media outside of books and magazines—documentaries, YouTube videos, blogs, and so forth. Thanks to them, it is increasingly unlikely for Mr. Doe—and Ms. Roe—to labor under the last of Ward’s misconceptions.

No doubt any successful author of a popular exposition of evolution bears in mind the misconceptions that the general reader is likely to have and attempts to compose the text in order to defuse them. But I think that Ward deserves credit for doing so explicitly. To be sure, the eight misconceptions listed in the first chapter of Evolution for John Doe aren’t the only eight misconceptions that Ward was evidently bearing in mind. (For instance, when he is talking about acquired characteristics, he is careful to note “there is nothing aggressive in the technical meaning. A plant or an animal does not make any effort to get hold of a character.”) And I don’t agree with all of his ways of attempting to defuse the misconceptions, especially his omission of human evolution. But Evolution for John Doe is a good model, especially when the misconceptions it lists and endeavors to defuse are still prevalent today among the general public. And these aren’t the only misconceptions that are prevalent today among the general public—which is a good thing, actually, since misconceptions are the fodder for Stephanie Keep’s Misconception Monday series!