In November, I attended WGBH’s forum on digital media in STEM learning. The topic: climate education. NCSE’s friends from the Alliance for Climate Education (ACE) were there in force, as were representatives from NOAA Education, NASA, PBS NewsHour Student Reporting Labs, and Young Voices for the Planet. This is in no way a complete list of presenters. I saw presentations on everything from using video game environments to help students learn about anthropogenic impacts on climate, to an incredible demonstration on the power of spoken word poetry to spur understanding and change. It was all inspiring and energizing. I was enthusiastically texting Minda Berbeco, NCSE’s climate education guru, constantly.

Among all the awesome exhibitions was one standout. Juliette Rooney-Varga and Angélica Allende Brisk’s presentation on the Climate Interactive world climate negotiations simulation was mesmerizing. To accompany their talk, they showed a video. In it, Rooney-Varga is at Cambridge Ringe-Latin school presenting a unit on climate change. The kids are totally bored, disengaged, picking their nails, and staring at the floor. This is despite what Rooney-Varga insists was a really compelling lecture! Then, they begin the simulation. Cut to those same kids in a heated discussion about mandatory carbon reductions and reforestation. They were almost yelling at each other! Not in a “Hey stop that!” kind of way, but more of a “whoa, you guys are into this” way. According to Allende Brisk, they played out the simulation over two days. In the night between sessions these formerly apathetic teenagers watched CSPAN to prepare for day 2. CSPAN! What got them so engaged? What was this simulation and why doesn’t everyone know about it?

About a week later, I was very disappointed to learn that my church’s climate advocacy group had run the simulation on Halloween—I’d missed it! But then word got out that they’d be running the simulation for a second time in mid-December. I signed up right away and last Sunday, I got to see what all the fuss was about.

About a week later, I was very disappointed to learn that my church’s climate advocacy group had run the simulation on Halloween—I’d missed it! But then word got out that they’d be running the simulation for a second time in mid-December. I signed up right away and last Sunday, I got to see what all the fuss was about.

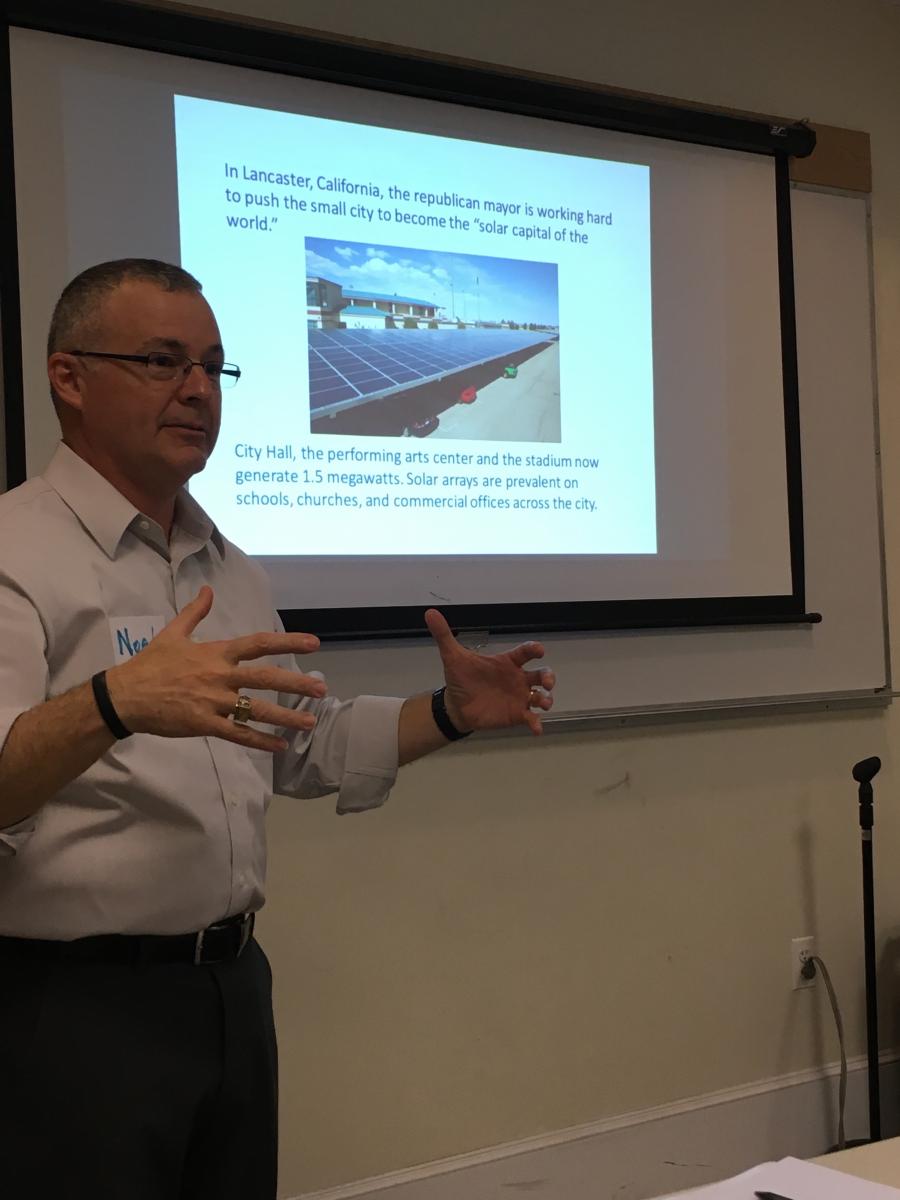

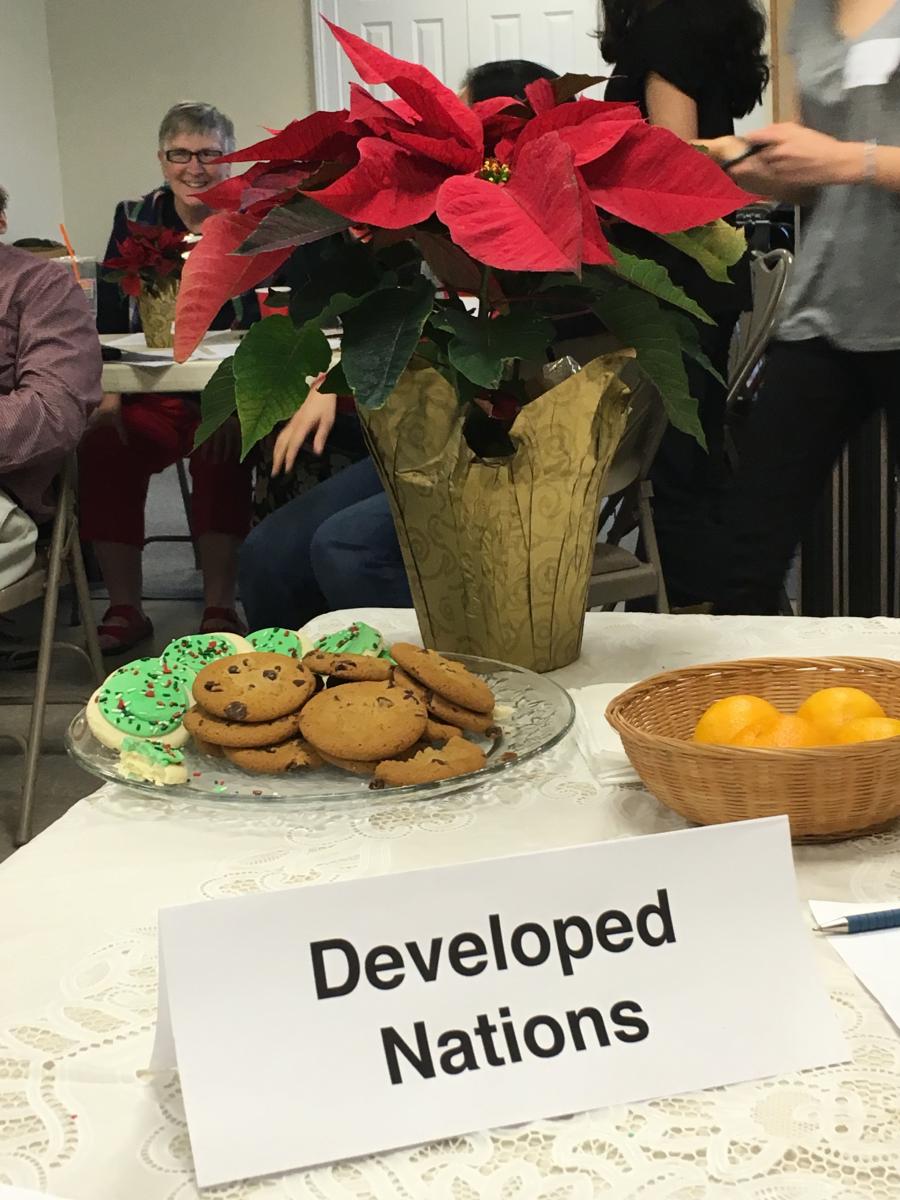

My simulation was run by Noel Zamot from MIT’s Sloan School of Management, one of the organizations that developed the interactive program. The basic set-up is that participants get divided into three groups: “developed nations” (led by the US, EU, Russia, and Japan) “developing A nations” (led by Brazil, India, and China), and “developing B nations” (which includes most of Africa, South and Central America, the Middle East, and small island nations). Once divided up, we experienced immediate stratification. The developed nations got a table with a nice tablecloth, cookies, a big, lovely pointsetta, water, and comfortable chairs. The developing A nations got a table and chairs, but no tablecloth. Cookies, but not such nice ones. A smaller pointsetta. As for developing B representatives, they got cushions on the floor.

I was a member of the developed nations delegation. The cookies and tablecloth made me feel guilty…but also kind of important. Probably the exact intention of these props. Each delegation got a 2-page briefing that included background, data, and considerations. From mine, I learned that, unequivocally, the CO2 emissions that brought on this crisis were our doing. However, lately our emissions had been declining. Now the developing A nations were the top emitters. I also learned that most of the delegation came from countries whose citizens supported climate change action—but that powerful fossil fuel interests were doing their best to oppose meaningful change. Also of note, we have the most money—by a lot. The GDP of the developed nations was roughly 6–7 times that of the other nations.

I was a member of the developed nations delegation. The cookies and tablecloth made me feel guilty…but also kind of important. Probably the exact intention of these props. Each delegation got a 2-page briefing that included background, data, and considerations. From mine, I learned that, unequivocally, the CO2 emissions that brought on this crisis were our doing. However, lately our emissions had been declining. Now the developing A nations were the top emitters. I also learned that most of the delegation came from countries whose citizens supported climate change action—but that powerful fossil fuel interests were doing their best to oppose meaningful change. Also of note, we have the most money—by a lot. The GDP of the developed nations was roughly 6–7 times that of the other nations.

With this information in mind, we huddled and came up with our first round pledges. When would we stop accelerating CO2 emissions? When would we start making emissions decline, and by how much? Would we pledge to plant forests? To stop clearing forests? And how much money would we kick in to help other countries?

Our goal: keep global warming below 2℃.

Find the answer. Save the world.

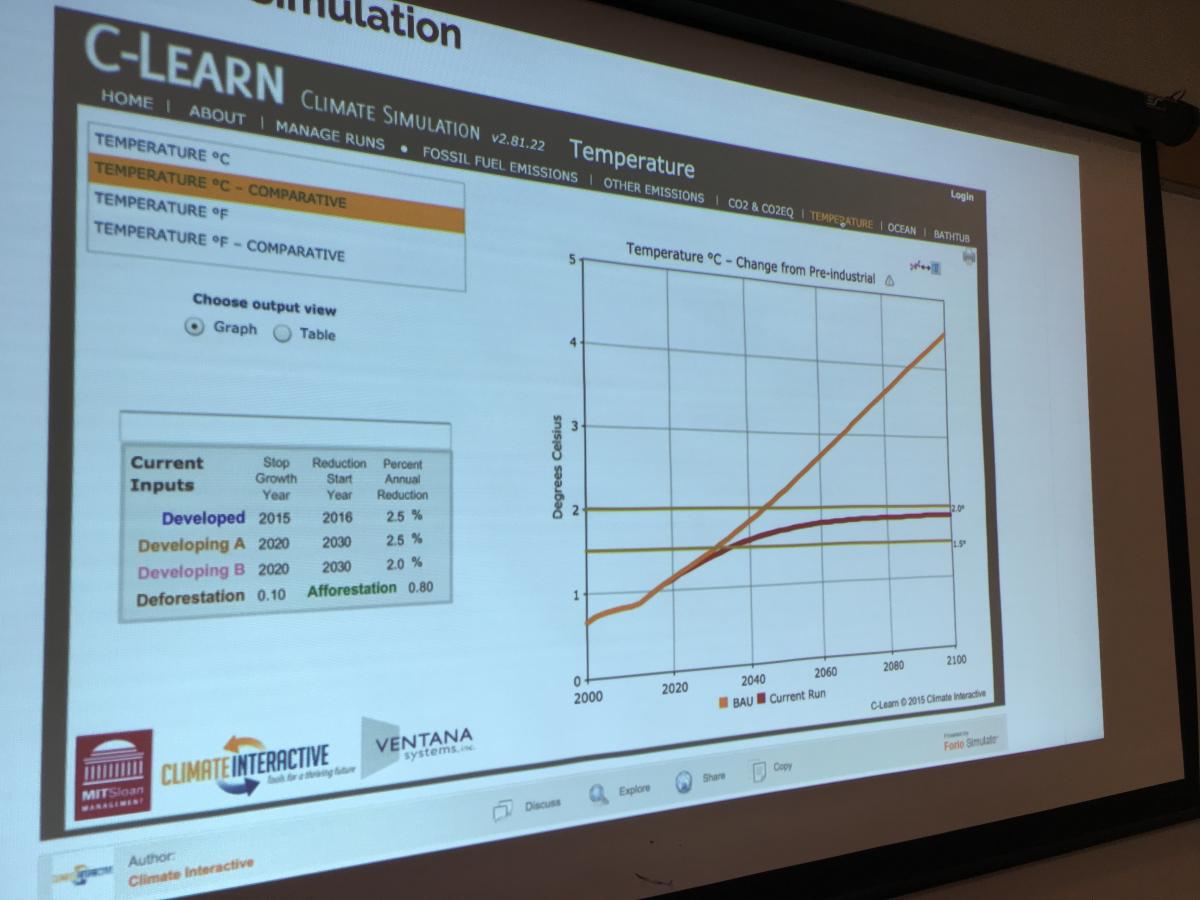

We were flying pretty much blind in this first round. My delegation proposed kicking in $67 billion of the $100 billion goal since we were, at present, emitting about 2/3 of global CO2. We thought that sounded fair. We also thought it’d take about five years to stop accelerating CO2 emissions and another fifteen to make them start to decline. Other groups presented their numbers. When they were put into the simulator we came nowhere near the < 2℃ goal. Sorry Boston, we just put you under water. Things looked bleak.

When we were sent back to the drawing board, our facilitator encouraged us to talk to each other more and to use outside resources (e.g., our phones) to help us make decisions. My group realized that we didn’t have to wait until 2020 to stop accelerating emissions. After all, we were already on a downward trend! Wonderful! We also learned from other delegations that they were going to contribute nothing to the pot. The developed nations were going to be footing this bill in its entirety.

That realization emboldened us. Okay, fine, we’ll pay for it—but in exchange, the other delegations were going to have to make deeper cuts and faster. We started making demands and then the other delegations would shoot back that this was all our fault, so we should back off. I found myself telling a high school student from the developing nations, in my best “strict mother voice,” that if they wanted our money, they had to reduce deforestation even further and start CO2declines by 2030—not 2040. After all, I said, you guys are the problem now. Meanwhile, the poor developing B nations were talking about how they’d really appreciate it if we could solve this so they wouldn’t be under water. Somewhere in there, they also stole some of our cookies. They said it was “the least we could do.”

That realization emboldened us. Okay, fine, we’ll pay for it—but in exchange, the other delegations were going to have to make deeper cuts and faster. We started making demands and then the other delegations would shoot back that this was all our fault, so we should back off. I found myself telling a high school student from the developing nations, in my best “strict mother voice,” that if they wanted our money, they had to reduce deforestation even further and start CO2declines by 2030—not 2040. After all, I said, you guys are the problem now. Meanwhile, the poor developing B nations were talking about how they’d really appreciate it if we could solve this so they wouldn’t be under water. Somewhere in there, they also stole some of our cookies. They said it was “the least we could do.”

I completely understood the passionate high school students now—I was one of them. Even though I knew it was a simulation, the whole thing got very emotional and we were all heavily invested in the experience. When our final negotiations—which came down to the wire—resulted in a warming of “just” 1.9℃, we cheered.

Zamot ended the session by comparing our experience to that of the first group that ran their simulation during Halloween. They had failed to get below 2℃ warming. Most everyone left feeling frustrated and angry, not cautiously optimistic and energized like us. What was the difference, he asked? I offered: Well, we knew it could be done. COP21 was over, the deal was inked. It was possible—we just had to find the way. There were murmurs of agreement.

Zamot ended the session by comparing our experience to that of the first group that ran their simulation during Halloween. They had failed to get below 2℃ warming. Most everyone left feeling frustrated and angry, not cautiously optimistic and energized like us. What was the difference, he asked? I offered: Well, we knew it could be done. COP21 was over, the deal was inked. It was possible—we just had to find the way. There were murmurs of agreement.

COP21 is already having an effect. The impossible is always possible. And, as the medal Zamot showed us as his last slide said, it's not going to be easy, but it's going to be worth it.

Are you a teacher and want to tell us about an amazing free resource? Do you have an idea for a Misconception Monday or other type of post? Have a fossil to share? See some good or bad examples of science communication lately? Drop me an email or shoot me a tweet @keeps3.