I was recently reading through “The Passing of Evolution,” George Frederick Wright’s contribution to The Fundamentals (1910–1915). Wright (1838–1921) was a minister and self-educated geologist who, under the tutelage of the botanist Asa Gray, became (as Ronald Numbers describes him in The Creationists [1992]) “one of Darwin’s most enthusiastic advocates.” But in the 1880s, when he was a professor at Oberlin College, “the thrust of his efforts shifted from defending evolution and the scientific enterprise against biblical literalists to defending the historical accuracy of the Bible against critics who applied evolution to the making of the Bible itself,” and by the time that A. C. Dixon was recruiting authors for The Fundamentals, he was a natural choice to be asked to contribute a screed against evolution.

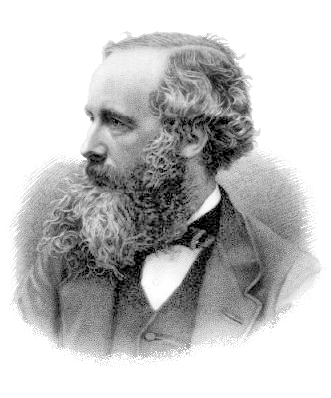

Having recently read Nancy Forbes and Basil Mahon’s book about the nineteenth-century British physicists Michael Faraday and James Clerk Maxwell, I was struck by the following passage in “The Passing of Evolution”:

Of this, as of every other variety of evolution, it can be truly said in the words of one of the most distinguished physicists, Clerk Maxwell: “I have examined all that have come within my reach, and have found that every one must have a God to make it work.” By no stretch of legitimate reasoning can Darwinism be made to exclude design. Indeed, if it should be proved that species have developed from others of a lower order, as varieties are supposed to have done, it would strengthen rather than weaken the standard argument from design.

That might sound as though Wright is going to defend a form of theistic evolutionism, sensu lato, but in fact he continues, “the proof of Darwinism even is by no means convincing,” and so forth. But what about that Maxwell quotation?

The earliest instance of the quotation I was able to find was, as it happens, from a “condensation” of a talk that Wright himself gave to the American Association for the Advancement of Science meeting in Boston in 1898, published in the magazine Public Opinion in the same year:

Lord Kelvin and the late Clerk-Maxwell, two of the greatest physicists of the century, voiced the general verdict when they said, that on examination of systems of materialism every one of them was found to require a God to make it work; thus leading to the opening announcement in Genesis that “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.”

So was it Kelvin or Maxwell (or both in unlikely chorus)? And was it not a verbatim quotation? The fact that the author was credited by Public Opinion as “Frederick G. Wright” suggests the possibility of error anyhow. But when a retooled version of the talk appeared under the title “The Accord of Science with the Bible” in 1902, it contained:

After tracing the protean forms of matter down to the ultimate atom, with which the chemist deals in all his formulae, Clerk-Maxwell affirms that they bear every mark of being “manufactured articles,” and, after having traced to its limits every variety of evolutionary theory, he affirmed with the utmost confidence that every one of them must have a God to make it work. Thus are these philosophers [Kelvin, Faraday, and Maxwell] brought back to almost the identical opening words of Genesis as the statement of their highest philosophy.

The same passage occurs in the entry for “Bible and Science, Accord of” by Wright in The New Standard Encyclopedia (1907). So, judging from the retooled version, it was Maxwell, but not necessarily a verbatim quote, and it may have appeared along with a claim about atoms as “manufactured articles.”

As it happens, Maxwell (above) mentioned atoms as “manufactured articles” in a conspicuous venue: his article on “Atom” for the ninth edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica (1875). The phrase is not Maxwell’s invention, as he explained, but John F. W. Herschel’s, from his Preliminary Discourse on the Study of Natural Philosophy (1830). (It was he who later dubbed the idea of natural selection “the law of higgledy-pigglety [sic],” by the way.) Herschel notes that atoms come “in a very limited number of groups or classes”—elements—“all of the individuals of each of which are, to all intents and purposes, exactly alike in all their properties.” That uniformity calls for explanation; Herschel infers that each atom must be therefore a “manufactured article” (emphasis in original) produced by a single agent intending to produce a uniform set of atoms.

Maxwell was evidently sympathetic to the argument, although not uncritically. In the article on “Atom,” he observed that because there are “three kinds of usefulness in manufactured articles—cheapness, serviceableness, and quantitative accuracy,” it was unclear how the argument was intended to run. Replying to a correspondent (Charles John Ellicott, the Bishop of Gloucester and Bristol, if you must know) in 1876, he seemed to endorse the argument on a reading of “manufactured article” where the uniformity is “a uniformity intended and accomplished by the same wisdom and power of which uniformity, accuracy, symmetry, consistency, and continuity of plan are as important attributes as the contrivance of the special utility of each individual thing.” But what about “a God to make it work”? You’ll see in part 2.