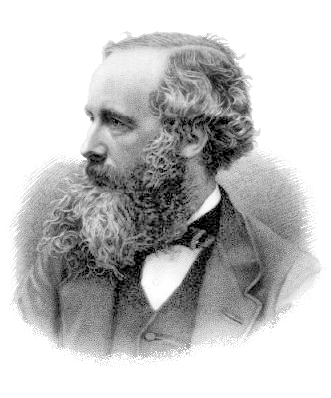

In part 1, I tried to verify a quotation supposedly from James Clerk Maxwell (right), who, according to George Frederick Wright’s “The Passing of Evolution,” said of all systems of evolution, “I have examined all that have come within my reach, and have found that every one must have a God to make it work.” Previous invocations of Maxwell by Wright suggested that it might have occurred along with a discussion of atoms as “manufactured articles,” which points to Maxwell’s article on “Atom” for the ninth edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica (1875). (Also a possible candidate is Maxwell’s “Molecules,” a public lecture published in Nature in 1873; it prefigures and is reflected in the encyclopedia article, so it requires no special treatment here.)

But the phrase “I have examined all that have come within my reach, and have found that every one must have a God to make it work” attributed to Maxwell by Wright is absent from the article on “Atom.” I was about to conclude that Wright confabulated it when I stumbled across the obituary for Maxwell by William Garnett in the November 13, 1879, issue of Nature. There it is claimed:

About three weeks ago he remarked that he had examined every system of Atheism he could lay hands on, and had found, independently of any previous knowledge he had of the wants of men, that each system implied a God at the bottom to make it workable.

Similarly, in Lewis Campbell and William Garnett’s The Life of James Clark Maxwell (1882), Maxwell’s cousin and friend Colin Mackenzie, who was present during Maxwell’s final illness, is quoted as reporting Maxwell as saying, “I have looked into most philosophical systems, and I have seen that none will work without a God.” Mackenzie was probably also the source for the obituary’s version.

As it happens, Wright used the “to make it workable” version in his The Logic of Christian Evidences (1881). But it then evidently mutated in his memory to the “make it work” version, and the types of system in question similarly shifted from atheism through materialism to evolution. Still, granting the accuracy of Colin Mackenzie’s and William Garnett’s reports, the distortions are not overly great.

It is noteworthy that Wright never claimed that Maxwell rejected evolution. (Today’s creationists, e.g., those at the Institute for Creation Research, are not so discerning.) In the article on “Atom,” Maxwell mentions biological evolution in the context of the question of why all molecules of a given type have the same properties. In the course of considering a number of possible types of explanations, he broaches the idea of a more or less evolutionary approach, swiftly rejecting it on the grounds that

a theory of evolution of this kind cannot be applied to the case of molecules, for the individual molecules neither are born nor die, they have neither parents nor offspring, and so far from being modified by their environment, we find that two molecules of the same kind, say of hydrogen, have the same properties, though one has been compounded with carbon and buried in the earth as coal for untold ages, while the other has been “occluded” in the iron of a meteorite, and after unknown wanderings in the heavens has at last fallen into the hands of some terrestrial chemist.

In so doing, Maxwell in effect grants that a theory of evolution can be applied to the case of living things. (He is cagey, I admit, writing only that “it has been found possible to frame a theory of the distribution of organisms into species by means of generation, variation, and discriminative destruction,” without going so far as to endorse the theory here.) He then suggests that the question can be answered in terms of the atoms of which the molecules are composed—but the problem reasserts itself at the level of atoms.

Thus Maxwell was arguably a creationist at least when it comes to atoms. (I generally prefer a stricter definition of “creationism,” as involving a rejection of biological evolution in favor of a supernatural creation, but I couldn’t resist here.) It is particularly visible in the conclusion to the lecture published in Nature, in which he declaimed, with reference to atoms,

They continue this day as they were created, perfect in number and measure and weight [compare here the apocryphal Wisdom of Solomon 11:20], and from the ineffaceable characters impressed on them we may learn that those aspirations after accuracy in measurement, truth in statement, and justice in action, which we reckon among our noblest attributes as men, are ours because they are essential constituents of the image of Him Who in the beginning created, not only the heaven and the earth, but the materials of which heaven and earth consist.

But although Maxwell was a serious Christian, he was leery of trying to support his faith with science, regarding inferences from science to theology as illegitimate and dangerous. And although he was repeatedly importuned to join the Victoria Institute, which was established to combat the pernicious effects of books like Darwin’s Origin, he firmly declined—hardly the decision of a dyed-in-the-wool antievolutionist!