The latest battle over Texas textbooks is coming to a head. Next week, the state board of education will vote to adopt social studies textbooks, setting the list of books approved for use in history, geography, social studies, economics, and other classes for next decade. Normally we at NCSE don’t spend much time looking at social studies textbooks, but climate change comes up in several of the books and we looked them over to make sure the science was right.

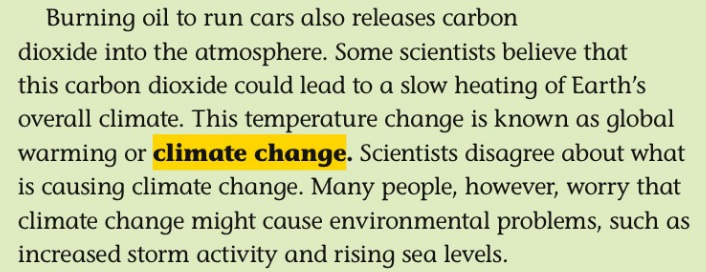

As I discussed before, books from two of the largest publishers were particularly worrisome because they handled the question of what causes climate change as if it were still subject to scientific dispute. A book from Pearson claimed that “scientists disagree about what is causing climate change,” while a World Cultures and Geography teachers' edition from McGraw-Hill contains an extended exercise in which students were asked to judge “which sides evidence is more convincing?,” given an excerpt from the widely-respected IPCC explaining how scientists know humans are causing climate change and another from the climate change-denying Heartland Institute insisting that humans may play no role at all. (I've posted screengrabs of the two excerpts if you'd like more detail.)

As I discussed before, books from two of the largest publishers were particularly worrisome because they handled the question of what causes climate change as if it were still subject to scientific dispute. A book from Pearson claimed that “scientists disagree about what is causing climate change,” while a World Cultures and Geography teachers' edition from McGraw-Hill contains an extended exercise in which students were asked to judge “which sides evidence is more convincing?,” given an excerpt from the widely-respected IPCC explaining how scientists know humans are causing climate change and another from the climate change-denying Heartland Institute insisting that humans may play no role at all. (I've posted screengrabs of the two excerpts if you'd like more detail.)

Both publishers took a stab at correcting those flaws, but only one succeeded.

Pearson’s revision states:

Burning fuels like gasoline releases carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Carbon dioxide, which occurs both naturally and through human activities, is called a greenhouse gas, because it traps heat. As the amounts of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases increase, the Earth warms. Scientists warn that climate change, caused by this warming, will pose challenges to society. These include rising sea levels and changes in rainfall patterns.

Where the old passage equivocated about the state of the science, this passage forthrightly states the major conclusions of the science, and gives students a clear and accurate foundation for discussing climate change’s consequences for society. The original passage held those conclusions at arm’s length, attributing uncontroversial stances only to “some scientists” or “many people.” The new language may need a bit more editorial polishing, but it gets the science right, and that’s key.

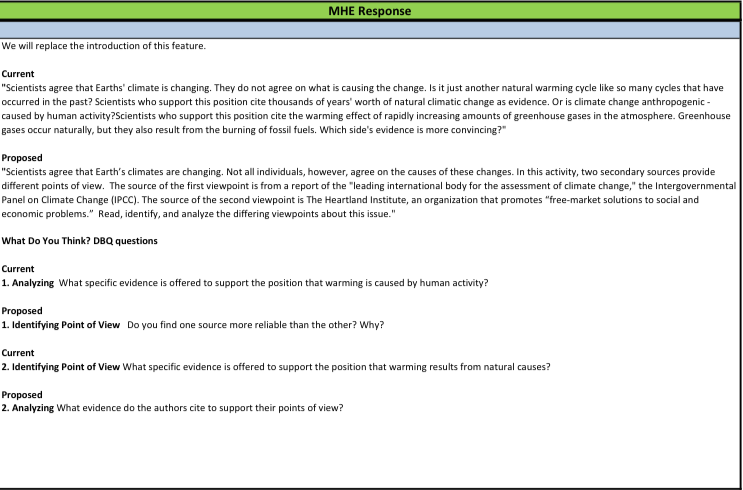

McGraw-Hill’s revisions (click the image at the right to embiggen) are not nearly so thorough, and don’t get to the heart of the flaws in this exercise. The original claims that scientists “do not agree on what is causing the [climate] change,” suggesting that they can’t decide whether it is “another natural warming cycle like so many cycles that have occurred in the past,” or caused by humans. The revision continues to acknowledge that scientists agree that the climate is changing, but states “Not all individuals, however, agree on the causes of these changes.” It now identifies IPCC as “the leading international body for the assessment of climate change,” where it gave no background before, and refers to Heartland as “an organization that promotes free-market solutions to social and economic problems.”

McGraw-Hill’s revisions (click the image at the right to embiggen) are not nearly so thorough, and don’t get to the heart of the flaws in this exercise. The original claims that scientists “do not agree on what is causing the [climate] change,” suggesting that they can’t decide whether it is “another natural warming cycle like so many cycles that have occurred in the past,” or caused by humans. The revision continues to acknowledge that scientists agree that the climate is changing, but states “Not all individuals, however, agree on the causes of these changes.” It now identifies IPCC as “the leading international body for the assessment of climate change,” where it gave no background before, and refers to Heartland as “an organization that promotes free-market solutions to social and economic problems.”

This is progress of a sort. Students need to know who the authors are and how they reached their conclusions in order to evaluate the passages, and this revision provides at least a bit of that context. But the fundamental problem remains that climate change denial is being presented as if it were a credible and accurate take on the science. It isn’t. It doesn’t belong in classrooms.

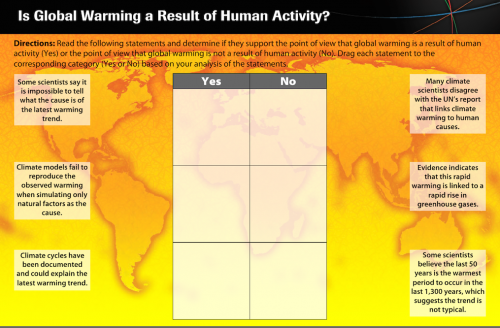

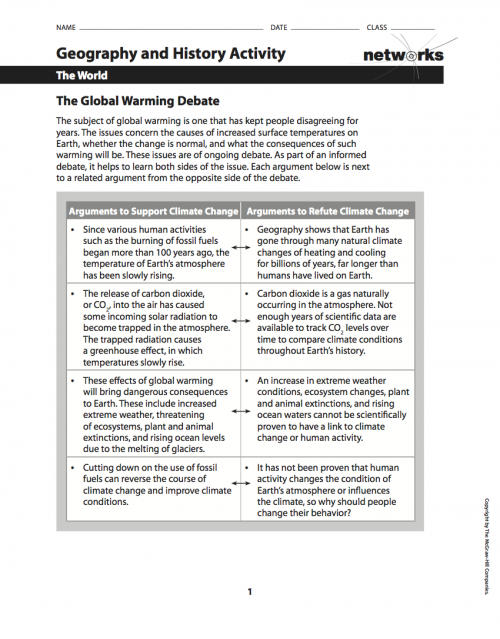

Worse yet, in exploring the textbook further, I located a series of related instructional resources in the textbook (including an interactive web feature which I screengrabbed to the right, and a handout for students, below, click either image to embiggen) which seem to adopt the flawed and error-laden Heartland Institute claims as the textbook’s own view. It’s one thing to present someone’s views in their own words for purposes of discussion, but quite another, as in these handouts and online exercises, to present them without distancing the textbook from the false claims. In both the interactive feature (the top screengrab) and the handout (below), students are given equal numbers of claims that support or "refute" climate change, and students are asked to place them in the right column as if each was of equal validity, relevance, and scientific accuracy. How could students fail to come away from this flawed exercise without the misconception that there is equal evidence for and against the role of humans in climate change? If only the students were asked to check each statement's accuracy against the list of common denialist errors at SkepticalScience.com!

Worse yet, in exploring the textbook further, I located a series of related instructional resources in the textbook (including an interactive web feature which I screengrabbed to the right, and a handout for students, below, click either image to embiggen) which seem to adopt the flawed and error-laden Heartland Institute claims as the textbook’s own view. It’s one thing to present someone’s views in their own words for purposes of discussion, but quite another, as in these handouts and online exercises, to present them without distancing the textbook from the false claims. In both the interactive feature (the top screengrab) and the handout (below), students are given equal numbers of claims that support or "refute" climate change, and students are asked to place them in the right column as if each was of equal validity, relevance, and scientific accuracy. How could students fail to come away from this flawed exercise without the misconception that there is equal evidence for and against the role of humans in climate change? If only the students were asked to check each statement's accuracy against the list of common denialist errors at SkepticalScience.com!

This is not to say that any exercise like this one would be doomed. The exercise could focus instead on an active scientific debate, like how much sea level rise we can expect in the next century. Or if it's necessary to include the Heartland Institute, they've staked out a series of policy positions on how and whether we respond to climate change, which could be contrasted with statements from impartial sources like IPCC or the National Climate Assessment, or from advocacy groups pushing for vigorous responses to climate change. Students could still be asked to evaluate the different viewpoints and examine how sources marshal evidence. But by shifting from a debate about a scientific conclusion to a policy question, the danger of the book reinforcing false scientific claims would be reduced and the book would stay more clearly focused on social studies and how science shapes society, than purely on the science (which is a discussion more appropriate for science classes).

At this point, McGraw-Hill’s textbook stands as the lone holdout. Every other publisher we had highlighted in our initial report has addressed and corrected the factual errors. I believe McGraw-Hill can get the science right in their textbook, too. And if they don’t do that for Texas, I’m sure they’ll have to for adoption in California, Florida, and other states down the line. There’s still time to sign a petition calling on McGraw-Hill to join the other publishers in fixing their textbook, and to contact the board of education and ask them to insist that McGraw-Hill fix these factual errors.