We humans are natural storytellers. For tens of thousands of years we have told and retold stories around campfires and in royal chambers and religious gatherings, in genres ranging from song to poetry, from performance to film. Many of the stories significant enough to survive history’s winnowing fan wer e about events so huge and traumatic that they became pillars of our world view and self-understanding: stories about great floods, fires, volcanic eruptions, deadly landslides, protracted wars, catastrophic plagues and famines, and more.

e about events so huge and traumatic that they became pillars of our world view and self-understanding: stories about great floods, fires, volcanic eruptions, deadly landslides, protracted wars, catastrophic plagues and famines, and more.

When we don’t make up stories ourselves, we borrow them from other people, cultures, and times. For centuries we have appropriated stories for our own use, reformatting them to fit our age, geography, cultural norms, and literary styles. This appropriation and reuse of stories played a crucial role in the assembling of the Hebrew Scriptures. From many different strands of collective tribal experience during vast migrations into what would become the "Promised Land," scribes or scribal communities drew inspiration from the world around them. Hebrew theology thus reflects a history reaching across many centuries, and stretching from Egypt to Palestine, from Assyria to Mesopotamia.

One of the most dramatic stories from ancient Mesopotamia available to the Hebrew authors was the story of a great flood recorded in the Epic of Gilgamesh (18th century BCE). In this story the gods decided to destroy humanity essentially so they could get some sleep:

In those days the world teemed, the people multiplied, the world bellowed like a wild bull, and the great god was aroused by the clamor. Enlil heard the clamor and he said to the gods in council, “The uproar of mankind is intolerable and sleep is no longer possible by reason of the babble.” So the gods agreed to exterminate mankind.

Utnapishtim was warned by the god Ea to build a boat in which he and his family and animals would survive a fierce storm and a great flood. (Epic of Gilgamesh, Tablet XI)

The Hebrew authors of Genesis adapted this epic story from their Mesopotamian neighbors, elegantly restructuring the episode of random god-authored genocide to serve as an integral element of the story of salvation as told in the Hebrew Scriptures. The multiple gods became one God and the insomniac caprice in Gilgamesh became God’s cleansing of an evil world and his re-creation and re-population of it through the line of Noah. The flood story thus set the Hebrew theological stage for the calling forth and covenant with Abraham, the spiritual patriarch of the Israelite people.

As you can see, the story of Noah was already borrowed and given a new purpose by Hebrew scribes. It has been retold countless times, and the theme is now being used by filmmaker Darren Aronofsky to tell his own idiosyncratic tale of environmental retribution and redemption.

I am sure the Noah story is by now out of copyright. Since it is the patrimony of all humankind, it is curious that so many people are getting their knickers in a twist about yet another Hollywood filmmaker borrowing themes, characters, and plot lines for his own use. To be sure, this portrayal of Noah is substantially different from the Hebrew Scriptures. But let's face it—the biblical story itself took substantial liberties with the ancestral flood story that preceded it. It is largely fundamentalists committed to a literal interpretation of the Bible (when that suits their purposes) who want to hijack the Noah story as their exclusive property. Eric Hovind of Creation Today complains:

Aronofsky is not interested in the Biblical record, fossil record, or hundreds of cultural records that testify to the Flood being a true event. He summed up his view of the Biblical account like this: “I don’t think it’s a very religious story, I think it’s a great fable that’s part of so many different religions and spiritual practices. I just think it’s a great story that’s never been on film.”

Aronofsky would no doubt agree with Hovind that it’s not a very religious story, as he never pretended it was in the first place! Not surprisingly, Ken Ham speaks even more starkly from the Creation Museum at Answers in Genesis:

Ultimately, there is barely a hint of biblical fidelity in this film. It is an unbiblical, pagan film from its start. It opens with: “In the beginning there was nothing.” The Bible opens with, “In the beginning God.” That difference helps sum up the problem I have with the film. The Bible is about the true God of creation; the movie does not present the true God of the Bible.

Again, I don’t think Aronofsky was claiming to represent the true God of the Bible, any more than the Hebrew scribes claimed in Genesis to represent Ea and his pantheon. Other creationists are even less polite in their criticism. Banana/hand design specialist Ray Comfort snidely remarks:

"Maybe they will even consider making a sequel called 'Muhammad,' where they portray him as an evil character as they did with Noah and see if Moslems file in two-by-two to see it. But they wouldn't dare malign Muhammad's character, because they know that there would be serious repercussions. With 'Noah' they have shown that they have no respect for Christians and Jews, by painting Noah as a psychopath."

David Klinghoffer of Seattle’s Discovery Institute wastes no time in connecting Aronofsky’s interpretation to the DI’s perennial bête noire, Charles Darwin:

This is just a totally different way of looking at the world, one with its scientific roots in Darwinian evolutionary theory. If humans are nothing more than animals with an attitude problem, no soul, no image of God, nothing genuinely, meaningfully exceptional about us—then a clean sweep of us from the surface of Mother Earth might make sense. That it produces twisted and ugly sentiments—fantasies of mass human death to make way for the beasts and the plants—is also true.

Perhaps oddest of all—odd because the Roman Catholic Church is not committed to a literal reading of the flood story—is the reaction of a Catholic priest employed (not surprisingly) by Fox News. Father Jonathan Morris warns that "They missed the mark, and they’re going to pay for it dearly," because the film makers didn't start from the point of view of faith.

I plan to see Noah sometime this week, and will post my reflections on the artistic quality and messages of the film. The creationist reviews are a reminder of how parochial, unliterary, and, indeed, illiterate their readings are of texts both sacred and secular. These creationist groups have come to believe that they own Genesis, including Noah. The story of Noah, in Genesis or in movie theaters, is just that, a story not a history. As a story it belongs not only to Jews, Christians and Muslims, but also to people who no longer profess faith in Judaism, Christianity, Islam or any other faith. The Noah story covers three chapters of Genesis, in about as many words as a magazine article. It’s a story that has been borrowed, told, retold, changed, and adapted to the needs and concerns and lessons of many people over many millennia. The creationists' objection to any interpretation of the biblical flood story except their own boils down to “but that’s not how it really happened.” On that point, it seems likely that Aronofsky, Gilgamesh, and I would probably agree, but we also happen to know that that’s not the point.

Noah. The story of Noah, in Genesis or in movie theaters, is just that, a story not a history. As a story it belongs not only to Jews, Christians and Muslims, but also to people who no longer profess faith in Judaism, Christianity, Islam or any other faith. The Noah story covers three chapters of Genesis, in about as many words as a magazine article. It’s a story that has been borrowed, told, retold, changed, and adapted to the needs and concerns and lessons of many people over many millennia. The creationists' objection to any interpretation of the biblical flood story except their own boils down to “but that’s not how it really happened.” On that point, it seems likely that Aronofsky, Gilgamesh, and I would probably agree, but we also happen to know that that’s not the point.

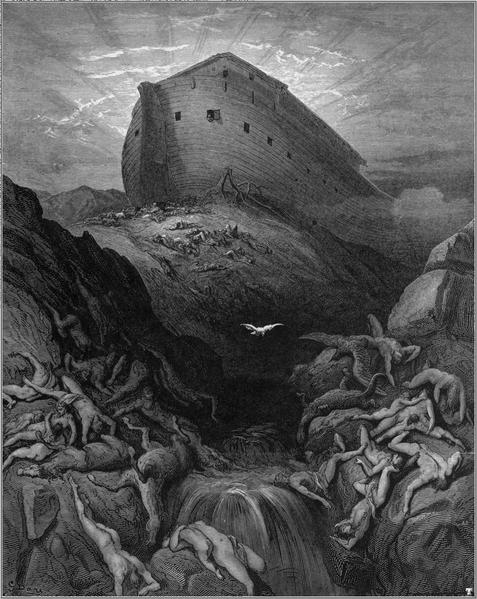

Images: 1. Le Lâcher de la colombe (The dove sent forth from the ark), Gustave Doré (1866-1870). 2. Noah's ark on the Mount Ararat, Simone de Myle, (1570)