I woke up last Thursday morning to an NPR report on a new human fossil find. I’m not in any way a morning person, so not a lot of detail made its way into my sleepy head, but I heard enough to know one thing: I’d be writing a blog on this…after coffee.

I’ve written about human evolution a few times here before, so by now you’re probably all familiar with my stance on it: It’s super cool and everyone should teach it. This latest discovery is so exciting that I can’t imagine any biology teacher not sparing a few minutes from the back-to-school “here’s how science works” introduction to talk about it. In fact, there is a major lesson in this story that plugs right into the introductory narrative—think science is boring? The discovery of Homo naledi involves serendipity, tons of mystery, a dash of controversy…and spelunking.

I’ve gotten ahead of myself, I know, but I’ve spent a good part of the day reading about this and I’m all a-twitter. But, okay, I’ll rewind and start at the beginning.

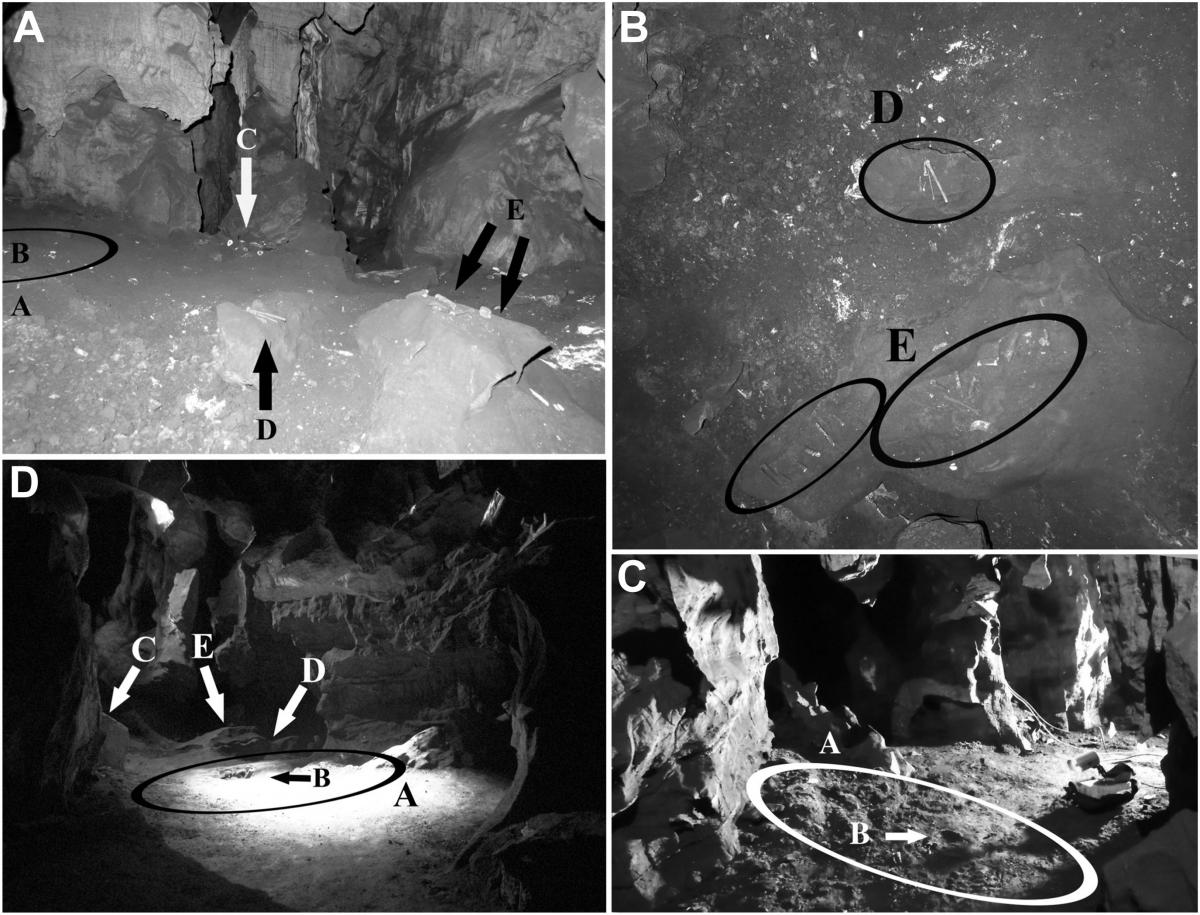

In 2013, a pair of spelunkers—yep, spelunkers—were exploring a popular cave in South Africa called Rising Star, just northwest of Johannesburg. Deciding that they wanted a challenge, the spelunkers took a road-less-traveled, and after squeezing through a 10-inch wide passage known as “Superman’s Crawl” and dropping down a 40-foot vertical shoot, they eventually found themselves in a chamber—a chamber, it turns out, full of bones. Hominin bones.

In 2013, a pair of spelunkers—yep, spelunkers—were exploring a popular cave in South Africa called Rising Star, just northwest of Johannesburg. Deciding that they wanted a challenge, the spelunkers took a road-less-traveled, and after squeezing through a 10-inch wide passage known as “Superman’s Crawl” and dropping down a 40-foot vertical shoot, they eventually found themselves in a chamber—a chamber, it turns out, full of bones. Hominin bones.

Quick reminder that a hominin is anything more closely related to modern humans than to modern chimpanzees. The chimp-human split happened about 5–6 million years ago, so our big bushy, branching hominin tree spans from 5–6 million years ago to the present. The earliest named species of our genus, Homo, is Homo habilis. Homo habilis lived between 2.4–1.4 million years ago in Eastern and Southern Africa. There is still some debate about whether Homo habilis really “deserves” the Homo designation, primarily because its brain was too small. Anthropologists love to talk about and compare brain sizes (or “cranial capacities”) and Homo habilis’ small cranial capacity (about half that of modern humans) makes it more of an Australopithecus than a Homo to some in the field.

Why am I telling you this? Because finding the “root” of the Homo genus is a big juicy bone for the big dogs in paleoanthropology. One of these big dogs is Lee Berger. Berger is of the opinion that Homo habilis shouldn’t really be a “Homo” at all, and has dedicated his career to finding the “true” root of our genus. What makes Berger somewhat unusual is where he looks for the fossils. Berger works in South Africa, which has had its share of remarkable hominin finds, but was not considered a likely location for the earliest Homos—until now. Because what was in that cave, that incredibly difficult to get to cave—were thousands of hominin bones belonging to, most think, an early Homo.

![Comparison of skull features of Homo naledi and other early human species. (Chris Stringer, Natural History Museum, United Kingdom - Stringer, Chris [10 September 2015]. "The many mysteries of Homo naledi". eLife 4: e10627. DOI:10.7554/eLife.10627. PMC: 4559885. ISSN 2050-084X.. Licensed under CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons)](http://ncse.com/files/Comparison_of_skull_features_of_Homo_naledi_and_other_early_human_species.jpg)

I want to pause here to share a little tidbit about how these bones were recovered. The daring spelunkers knew enough to alert a museum in Johannesburg about the bones, which is how Berger found out about them. Berger, however, is not a small man and there was no way he’d be able to get to them himself. So he apparently put out a call—on Facebook—for petite scientists and was able to assemble a team of six super-tiny super-scientists (all women [girl power!]) who could do the field work below while Berger watched on a computer screen from above. Over the course of a few weeks, the scientists pulled out 1,550 bones representing parts of at least fifteen individuals.

In case it isn’t obvious let me assure you that this is an astounding number of remains.  There aren’t close to fifteen well-represented individuals of any early hominin species. Only later hominins, like Homo heidelbergensis and Homo neanderthalensis have a better record, and their individuals have usually been found scattered in many locations, whereas all of Homo naledi (the name given to the new species, naledi means “Rising Star” after the cave it was found in) were found together. And the kicker? Berger’s team is positive that there are way more bones to pull up—the 1,550 they recovered came from a small portion of the cave—there is much more to discover.

There aren’t close to fifteen well-represented individuals of any early hominin species. Only later hominins, like Homo heidelbergensis and Homo neanderthalensis have a better record, and their individuals have usually been found scattered in many locations, whereas all of Homo naledi (the name given to the new species, naledi means “Rising Star” after the cave it was found in) were found together. And the kicker? Berger’s team is positive that there are way more bones to pull up—the 1,550 they recovered came from a small portion of the cave—there is much more to discover.

What happened next is pretty great. Berger assembled a team of more than fifty scientists, from newly graduated PhDs to experienced researchers. Together, they performed a six-week “blitzkrieg fossil fest.” Teams were set up to identify and reconstruct skulls, jaws with teeth, limbs… everyone working to figure out what the heck they had. In the end, what they had turned out to be—well, I’ll quote paleoanthropologist Fred Grine—“weird as hell.”