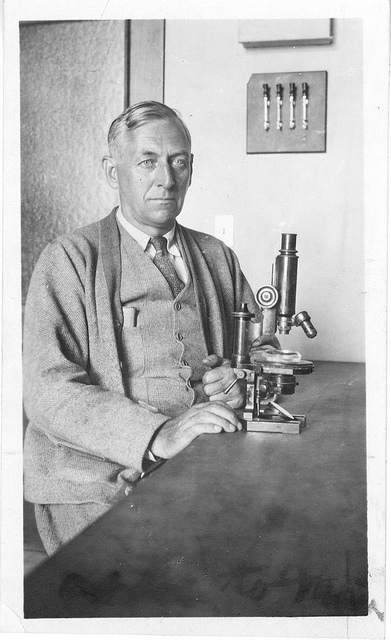

“Reluctant as he may be to admit it, honesty compels the evolutionist to admit that there is no absolute proof of organic evolution” (emphasis in original). That’s a passage from H. H. Newman’s essay “Is Organic Evolution an Established Principle?” published as chapter 4 in his 1921 collection Readings in Evolution, Genetics, and Eugenics. In the preface, Newman (right) explains that he has “for sixteen successive years presented in lecture form to large classes of students the subjects of evolution, genetics, and eugenics,” but he was never able to find a single book that covered the topics together to his satisfaction. But his collection of readings was intended not only for the college student but also for the general reader: “Apart from a few of the more technical details,” Newman promised, “the text seems to us very readable.”

It will not come as a shock, I trust, to learn that among the general readers who perused Newman’s collection were creationists. Without any effort to assemble a comprehensive list, I see that the quoted passage above appears in at least three Scopes-era creationist books: William A. Williams’s The Evolution of Man Scientifically Disproved (1925), with “we” mistakenly substituted for “he” and with the emphasis omitted; Charles Spurgeon Knight’s Both Sides of Evolution (1925), with the emphasis omitted; and Alonzo L. Baker and Francis D. Nicol’s Creation—Not Evolution (1926), again with the emphasis omitted. It’s not unheard of even today: a letter to the editor of the Walla Walla Union-Bulletin quoted the passage, with the emphasis omitted and with the year given as 1932, in 2013.

So was Newman skeptical about evolution? Not hardly. Born in Alabama in 1875, H. H. Newman—the initials are for Horatio Hackett—received his Ph.D. in zoology from the University of Chicago in 1905. After stints teaching at the University of Michigan and the University of Texas, he returned to become a member of the faculty at the University of Chicago. He published numerous articles and six books, including the widely used Readings in Evolution, Genetics, and Eugenics as well as Twins: A Study of Heredity and Environment (1937, with Frank N. Freeman and Karl J. Holzinger), a classic study comparing identical twins reared together, fraternal twins reared together, and identical twins reared apart. Newman retired in 1940, moving to Clearwater, Florida, where he died in 1957.

Although Newman’s obituary in Science describes him as “one of the outstanding pioneers in the development of the science of human genetics in America,” it is silent about his views on evolution. Newman himself was far from silent. “There is no rival hypothesis to evolution,” he wrote in his Outlines of General Zoology (1924), “except the out-worn and completely refuted one of special creation, now retained only by the ignorant, dogmatic, and the prejudiced”—shades of Richard Dawkins’s famous description of those who claim not to believe in evolution as “ignorant, stupid or insane (or wicked, but I’d rather not consider that)” comment in 1989! Moreover, Newman was among the scientific expert witnesses slated—but ultimately not allowed—to testify for the defense in the Scopes trial in 1925.

In his testimony, Newman discussed lines of evidence for evolution from comparative anatomy, taxonomy, serology (“the science of blood tests”), embryology, paleontology (focusing on horse and human evolution), geographic distribution, and genetics. On the status of evolution in general, he wrote, “The principle of evolution stands in the first rank among natural laws not only in its range of applicability, but in the degree of its validity, the extent to which it may lay claim to rank as an established law. It is the one great law of life. It depends for its validity, not upon conjecture or philosophy, but upon exactly the same sorts of evidence as do other laws of nature.” The talk about evolution as a law is misguided, I think, but clearly Newman is not suggesting that evolution is in a bad way with regard to the evidence.

It would be surprising if, in the four years since Newman’s “Is Organic Evolution an Established Principle?” was published, he changed his mind significantly about the status of evolution, especially when the same seven lines of evidence appear in the 1921 essay (although in a different order: paleontology, geographic distribution, classification, comparative anatomy, serology, embryology, and genetics). And in general, the overall shape of the arguments in the 1921 essay and the 1925 testimony is more or less the same, suggesting that Newman returned to the former in composing the latter. Looking at the passage from “Is Organic Evolution an Established Principle?” with the reference to “absolute proof” in context, three facts about Newman’s discussion are noteworthy.

First, Newman is certainly willing to talk about organic evolution admitting of proof. “The nature of the proof of organic evolution,” he writes, consists in the fact that “using the concept of organic evolution as a working hypothesis it has been possible to rationalize and render intelligible a vast array of observed phenomena” (emphasis in original). Second, he offers almost no indication what “absolute proof” would be. There’s a hint that direct observation would constitute absolute proof, which strikes me as dubious, but the thought is undeveloped. Third, he is careful to minimize the significance of the lack of any “absolute proof” of evolution, noting, “there is no absolute proof of anything that depends on records of past events” or on unobservables—so history, geology, physics, and chemistry are all in the same boat.

None of those facts seems to have been acknowledged by the creationist writers to quote the passage from Newman that I’ve inspected. A lot quote the passage in isolation, giving no sense of the context. A few, such as William A. Williams in his The Evolution of Man Scientifically Disproved, seem at least to have read the original, since they quote one sentence or another from later in the article. But if any have accurately and completely conveyed Newman’s meaning, they have escaped my notice thus far. Doubtless the passage was so popular among creationist writers because of Newman’s (undocumented) suggestion that the evolutionist was only reluctantly compelled, by a sense of honesty, to acknowledge the lack of any “absolute proof” of evolution. It would have been nice if those quoting him had felt a similar compulsion.