In 1939, the great African American physician and surgeon Charles Drew organized a massive blood bank, shipping thousands of pints of plasma from New York City to Britain. The shipment saved lives as German bombs shredded English cities. The Red Cross soon brought Drew on board to coordinate its blood banking efforts, a necessary step as World War II expanded through Europe, the Pacific, and to American shores.

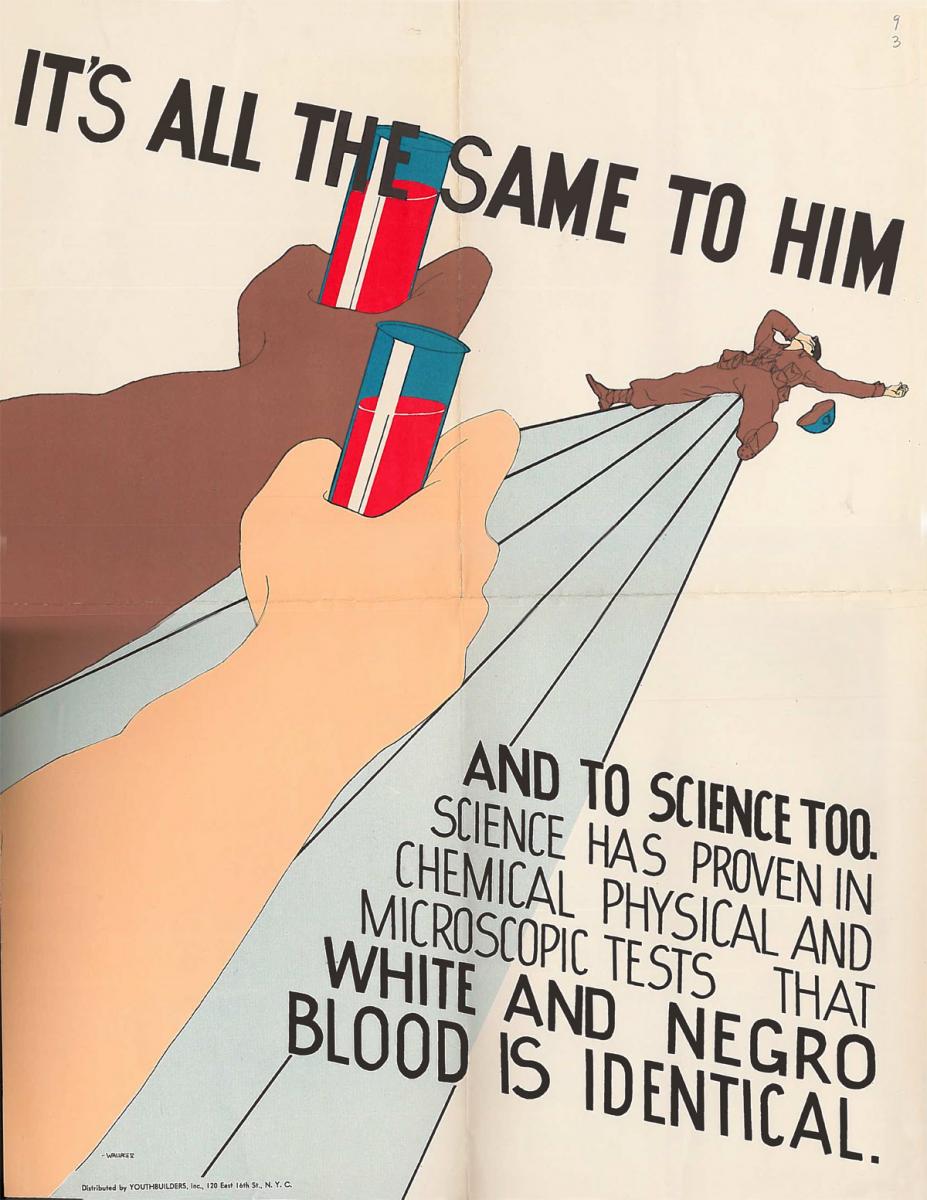

Poster distributed by Youthbuilders, the student group from New York City's PS 43, to protest segregated blood banks. Produced in 1945, reproduced here from the YWCA of the U.S.A. Records, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College. The poster was distributed along with copies of YWCA’s play “Blood Doesn’t Tell."

Poster distributed by Youthbuilders, the student group from New York City's PS 43, to protest segregated blood banks. Produced in 1945, reproduced here from the YWCA of the U.S.A. Records, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College. The poster was distributed along with copies of YWCA’s play “Blood Doesn’t Tell."Ironically, he could not donate his blood to the Red Cross blood bank. (Contrary to a popular myth, however, his death after a car crash was not due to his ironically being refused a blood transfusion.) The Red Cross’s policies initially prohibited donations from African Americans, and later required that donated blood to be segregated by race, a policy which persisted until 1949. (Arkansas mandated it until 1969, Louisiana until 1972). That policy was not regarded as scientifically necessary, but only as politically expedient. The surgeon general of the army explained to Assistant Secretary of War James J. McCloy, in 1941: “For reasons not biologically convincing but which are commonly recognized as psychologically important in America, it is not deemed advisable to collect and mix caucasian and negro blood indiscriminately.”

The idea of racially segregating blood was widely mocked, including by Langston Hughes in his column for the Chicago Defender. In his December 12, 1942 column Hughes wrote about draftees “passing for white” and happily serving in officially all-white units, and went on to observe:

an even better joke on our white folks is that that of colored soldiers in white units, is what is happening to the Red Cross blood bank in some of the Eastern cities. Many light and, to the eye, quite near-white Negroes have of late—so I have been told—given their blood most generously to the Red Cross.

In the process they did not mention the colored race, so naturally, their blood has gone into the white blood banks. Thus, by now, white plasma and colored plasma must be hopelessly scrambled together, and it amuses me to wonder how the Red Cross will ever get it straightened out. Even the charming mulatto ladies of Jim Crow Washington, so Eastern gossip has it, have gleefully added to this confusion, putting on their light makeup and baring their lovely arms to the needle for the sake of a patriotic and harmless little joke on unscientific Nordics.

One creative group of students took aim at the policy as well. A group from New York’s PS 43, “located on the fringe of Harlem” (according to the Defender’s account of 4/24/43), arranged a meeting between themselves and the school’s science teachers and staff from a large blood testing laboratory. Bernice Berthea, president of the school’s Youthbuilders club (a program from the City Board of Education aiming “to educate children for responsible citizenship in a democracy”), and Fred Stern, one of its members, donated blood (hers to represent African Americans, his to represent whites). The tests showed no differences due to race.

Any science student knows that publication is a key part of the scientific process. So the Youthbuilders created slides describing the experiment for use in science classes, and wrote an article about it for the school newspaper. An alumnus of the school designed a poster “showing the foolishness of blood segregation and its danger to the democratic principles of the American nation”; two hundred copies were produced and disseminated.

Moreover, the YWCA produced a play about the students’ effort, “Blood Doesn’t Tell: A Play About Blood Plasma and Blood Donors.” I got a scanned copy from the Sophia Smith Collection at Smith College, which includes instructions on how youth groups can present the play. The script is about what you’d expect, with the protagonist an “attractive young teacher” who breaks up a fight in which a white student mocks a black classmate on the grounds that “they don’t want colored people’s blood! It isn’t good enough!” The teacher takes the kids to a blood bank, where they see that blood types have nothing to do with race. “Could an Eskimo or a Zulu, for instance, have the same blood type as an Englishman or an Indian?,” the teacher asks. When the doctor says they could, actors are instructed to “show surprise and look at each other in amazement.” The students tour the center and see how blood is drawn, separated, and sent off to the front lines, and are inspired to make posters promoting blood donation. When the principal balks at having posters with black and white arms stretched out to donate blood, the teacher prevails by insisting:

I think it is important to let these boys and girls carry the truth about the situation to their community. They have a right to help, as they have been helped, by an honest presentation of the facts. It seems to me that this battle against ignorance is just as important as any battle on the war front. It can mean victory over hatred, division, prejudice and distortion. And that’s a victory we need very much in order to preserve and develop what is worthwhile in this country and in the world. We can’t discourage their honesty! If problems arise, they have a right to know the truth about such problems and to help solve them.

The true story, and the play’s plot, both offer powerful examples of how science education leads to political empowerment and, in time, to social change.

That change was also fomented among the directors of blood centers. One in Boston openly acknowledged defying the segregation order, while one in St. Louis, according to a fascinating paper by Thomas Guglielmo, “offered to throw out all Negro blood if anyone could tell which was which. No one could” (quoted, I think, from an internal Red Cross survey). Medical and scientific societies joined with civil rights groups in protesting the policy. It was lifted after the war, and after the military itself was finally desegregated.

There are a few valuable lessons from that struggle. First, it’s a reminder how science denial operates. Despite ample evidence from leading medical societies down to middle school students showing that blood was blood, and despite the clear awareness of that science by policymakers from the beginning, the policy persisted. Policymakers who could have relied on science instead kowtowed to ideological fears, risking the lives of injured soldiers and the principles of the society they were fighting to defend, all to shield this vicious policy.

Second, it’s a reminder of what we lose when we shut people out of science and medicine. While some people passed for white to thumb their nose at the policy, as Guglielmo observes, “perhaps the most widespread, everyday form of protest came from thousands of ordinary African Americans who decided against donating blood and money to the Red Cross.” Despite making up 10% of the US population, African Americans are recorded as only contributing about 1% of blood donations. It’s not that they were unpatriotic: African Americans enthusiastically served in the (segregated) armed forces, bought war bonds, and took part in other forms of sacrifice for the war effort. But where their contributions seemed to be devalued, they opted out. There’s some sort of lesson there.

Third, it’s a reminder that clever kids with good science teachers can and should raise some hell. When you supply some science and resources, people can do amazing things. The rise of DIYbio, open source lab gear, and the falling cost of gene sequencing all open up tremendous opportunities for our students (and interested hobbyists) if we give them the tools and knowledge they need, and don’t let ideology get in their way.