A friend e-mailed the other day wondering just how many people in the United States are young-earth creationists.

The answer begins with a question the Gallup poll has been asking since the early ’80s:

Which of the following statements comes closest to your views on the origin and development of human beings: human beings have evolved over millions of years from other forms of life and God guided this process, human beings have evolved over millions of years from other forms of life, but God had no part in this process, or God created human beings in their present form at one time within the last 10,000 years.

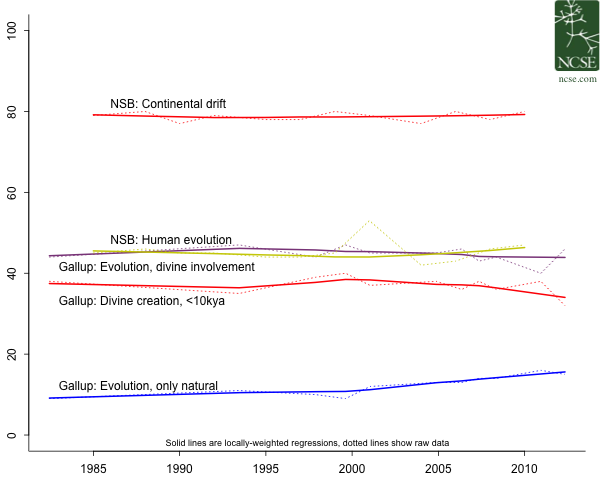

Around 44% have consistently endorsed that last option, a consistent 37% take the middle option (which could cover beliefs in intelligent design, various forms of old-earth creationisms, or theistic evolution), and about 12% back a nontheistic evolutionary account. This breakdown has been remarkably consistent over the decades.

Around 44% have consistently endorsed that last option, a consistent 37% take the middle option (which could cover beliefs in intelligent design, various forms of old-earth creationisms, or theistic evolution), and about 12% back a nontheistic evolutionary account. This breakdown has been remarkably consistent over the decades.

But do 44% of Americans really think human beings (and indeed, the universe) have only been around for ten thousand years? Modest changes in the question’s wording produce different results, which isn’t so surprising: as asked, the question tangles up attitudes toward evolution, theology, and chronology.

Consider a few different poll results:

In 2009, Pew stripped away the religious issues and explicit reference to the age of the earth by asking people if they agreed that “Humans and other living things have evolved over time due to natural processes” or alternatively “existed in their present form since the beginning of time.” Six in ten opted for evolution.

In 2005, when the Harris Poll asked people “Do you think human beings developed from earlier species or not,” 38% agreed that humans did develop from early species, but in the same survey, 49% agreed with evolution when asked: “Do you believe all plants and animals have evolved from other species or not?” So explicitly mentioning human evolution led to 11% of people switching from pro-evolution to anti-evolution. In a 2009 survey, Harris asked a Gallup-like question, in which only 29% agreed that “Human beings evolved from earlier species,” but in a separate question from the same poll, 53% said that they “believe Charles Darwin’s theory which states that plants, animals and human beings have evolved over time.” Placing the issue in a scientific context, with no overt religious context, yields higher support for evolution.

The National Science Board’s biennial report on Science and Engineering Indicators includes a survey on science literacy which, since the early 1980s, has asked if people agree that “Human beings, as we know them today, developed from earlier species of animals.” About 46% of the American public consistently agree with that option, about the same number who back the middle option in Gallup’s surveys.

Clearly, people respond to these subtle shifts in how the question is framed, taking a harder stance toward human evolution than to the idea that animals and plants evolve, and stepping away from evolution if it is pitched in opposition to religion. Pollster George Bishop surveyed the diversity of survey responses in 2006 and concluded: “All of this goes to show how easily what Americans appear to believe about human origins can be readily manipulated by how the question is asked.”

In 2009, Bishop ran a survey that clarifies how many people really think the earth is only 10,000 years old. In survey results published by Reports of NCSE, Bishop found that 18% agreed that “the earth is less than 10,000 years old.” But he also found that 39% agreed “God created the universe, the earth, the sun, moon, stars, plants, animals, and the first two people within the past 10,000 years.” Again, question wording and context clearly both matter a lot.

For more evidence that the number of true young-earthers is fairly small, consider another question from the survey run by the National Science Board since the early ’80s. In that survey, about 80% consistently agree “The continents on which we live have been moving their locations for millions of years and will continue to move in the future.” Ten percent say they don’t know, leaving only about 10% rejecting continental drift over millions of years. Though young-earth creationists often latch onto continental drift as a sudden process during Noah’s flood (as a way to explain how animals could get from the Ark to separate continents), they certainly don’t think the continents moved over millions of years. This question puts a cap of about 10% on the number of committed young-earth creationists, lower even than what Bishop found. More people in the NSB science literacy survey didn’t know that the father’s genes determine the sex of a baby, thought all radioactivity came from human activities, or disagreed that the earth goes around the sun.

In short, then, the hard core of young-earth creationists represents at most one in ten Americans—maybe about 31 million people—with another quarter favoring creationism but not necessarily committed to a young earth. One or two in ten seem firmly committed to evolution, and another third leans heavily toward evolution. About a third of the public in the middle are open to evolution, but feel strongly that a god or gods must have been involved somehow, and wind up in different camps depending how a given poll is worded.