For the last eight years, Joseph Levine, co-author of one of the most widely used biology textbook programs in the nation, has been teaching professional development courses for high school teachers through the Organization for Tropical Studies at the La Selva Biological Station in Costa Rica. The program, Inquiry in Rainforests, takes educators into the forest to develop their understanding of inquiry-based science in a field-based tropical environment. So when executives from Sony Pictures Entertainment were looking for someone to create an educational outreach website for the Will and Jaden Smith movie After Earth, parts of which were filmed at La Selva, Levine was a natural choice.

The website, Life after Earth Science, was launched with quality science, lesson plans and visually appealing videos. We caught up with Levine at his New England home to chat about the making of the web resource.

The website, Life after Earth Science, was launched with quality science, lesson plans and visually appealing videos. We caught up with Levine at his New England home to chat about the making of the web resource.

Q. What were your goals when creating this site?

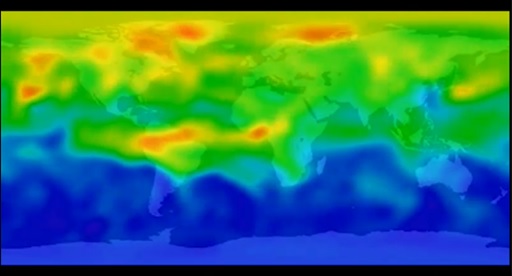

To my way of thinking, the web, particularly for high school students, should be a primarily visually-based experience; they don’t want to sit and read lots and lots of stuff. To find good videos on a bare-bones budget, we relied primarily on resources gathered by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center Science Visualization Service. I curated top picks to illustrate important concepts using NASA’s incredibly powerful, beautiful, and informative animations, which are based on hard data gathered by satellite. We were also generously granted permission to use several visuals by HHMI and by several other educators and researchers. Welcome to the Anthropocene had the best single visualization demonstrating the extent and depth of human impact on the biosphere.

Q. Do you have any concerns about mixing science fiction with real science? Do you think it could be confusing to students?

I was a science fiction fan long before I was a scientist. For me, the best science fiction is future telling; predictions of where science might take us. As educators and communicators, we need to examine as many ways as possible to excite young people about science, because understanding science requires effort; it doesn’t just happen. For a lot of people–especially teenagers–science seems abstract and far removed from their daily lives. But if they see someone like Jaden Smith saying, “you know we are really messing up the planet, and we need to do something about this,” it encourages kids to think about this issue. With that said, the website makes a very clear distinction between science and science fiction.

I was a science fiction fan long before I was a scientist. For me, the best science fiction is future telling; predictions of where science might take us. As educators and communicators, we need to examine as many ways as possible to excite young people about science, because understanding science requires effort; it doesn’t just happen. For a lot of people–especially teenagers–science seems abstract and far removed from their daily lives. But if they see someone like Jaden Smith saying, “you know we are really messing up the planet, and we need to do something about this,” it encourages kids to think about this issue. With that said, the website makes a very clear distinction between science and science fiction.Q. What are the big challenges to having kids understand climate change?

One challenge, of course, is the issue that led NCSE to pick up climate change as part of its purview: the almost unimaginably well-funded climate denialist movement. That movement constantly disseminates misinformation about climate science in a wide range of venues, so people get genuinely confused about what the real science actually says. Because kids are in an environment created by adults around them, they are  exposed to the misinformation too; so are their teachers for that matter.

exposed to the misinformation too; so are their teachers for that matter.

On top of that, the global climate system is fiendishly complex. So understanding that system, and then learning about how the system reacts to human activity, is challenging. Throw in a generous helping of misinformation and disinformation, and the task of educating students and the public becomes a monumental undertaking.

Yet another problem is the way that most of us–myself included–have traditionally taught human ecology. If we portray human interactions with the biosphere as an endless series of unmitigated disasters, people get depressed, rather than motivated. If we want people to make the effort needed to understand climate change, we need to show them how knowledge can empower them to make a difference. That’s why we included the site’s “take action” page. We wanted students and teachers to see that there are ways that individuals can make a difference.

Q. With so many issues that you could have addressed, how did you choose which areas to focus on for the website?

The website focuses on three main topics: global change, biodiversity, and mass extinction.

Global change is broken down into climate change, land-use change, nitrogen deposition, introduced species, and effects of increased atmospheric carbon dioxide other than its greenhouse effects. This structure was based on an article by Osvaldo Sala, which talks about anthropogenic drivers of ecological change. That work is continually being expanded and revised; there are a lot more drivers, and they affect different ecosystems differently. But these five drivers struck me as a useful place to start in a site aimed at a high school audience.

The biodiversity portion of the site tries to introduce the topic in a way that the general public can relate to by emphasizing the importance of ecosystems goods and services and the concept of sustainable development. Functioning, intact, and healthy ecosystems provide important services to human societies, and those services can be at risk if the environment is degraded too much.

The biodiversity portion of the site tries to introduce the topic in a way that the general public can relate to by emphasizing the importance of ecosystems goods and services and the concept of sustainable development. Functioning, intact, and healthy ecosystems provide important services to human societies, and those services can be at risk if the environment is degraded too much.

In the mass extinction section, we examine the background between “business as usual” extinction and mass extinction. Then we examine what paleontologists and other researchers are saying about the relationship between mass extinctions of the past and what many biologists see as an ongoing, human-caused mass extinction today.

The lesson plans were created by Marta Branch, a wonderful master teacher from Orcas Island in the state of Washington. Marta made certain to include lessons aimed at different levels of students, so that as many teachers as possible would find resources they could use.

Q. What has the reception been so far?

Teachers I’ve talked to are using the videos and lesson plans…and love them. The visual emphasis is very effective in encouraging a wide range of students to really pay attention. We also just received funding from the American Embassy in Costa Rica to translate the website into Spanish and disseminate it in Costa Rica and other Latin American countries.

Q. How can biology be used to teach us about climate change?

Climate data, meaning physical measurements of temperature, precipitation, and so on, are complex and very noisy. Climatologists sure have their work cut out for them! As biologists, however, we have a lot of “free” help in figuring out how climate change matters to living systems. Plants and animals in nature act like a huge array of living climate sensors. Each organism monitors its environment in its own way, and responds to changes in its own way. So plants and animals do a lot of measurement and analysis for us, and react in ways we can notice, including range shifts, and changing dates of blooming or breeding. So it’s easier to understand that climate is affecting the biosphere by peering through a biological lens, rather than by just looking at raw climate data.