When we got married, my wife and I set aside part of the cup of wine traditional in a Jewish service, to be finished when marriage was available to everyone. Days before our wedding, Judge Vaughn Walker had struck down marriage segregation in California, but that decision was on hold until last year, when the Supreme Court sustained his ruling. Two years ago, the Court also ruled that same-sex marriages authorized by states had to be recognized by the federal government. Today, my wife and I can finally finish that cup, because, in a 5-4 ruling, the Supreme Court struck down state laws segregating marriage by sex and sexuality (PDF). It’s a sweeping ruling with important consequences, and one that even a few years ago seemed unthinkable.

When we got married, my wife and I set aside part of the cup of wine traditional in a Jewish service, to be finished when marriage was available to everyone. Days before our wedding, Judge Vaughn Walker had struck down marriage segregation in California, but that decision was on hold until last year, when the Supreme Court sustained his ruling. Two years ago, the Court also ruled that same-sex marriages authorized by states had to be recognized by the federal government. Today, my wife and I can finally finish that cup, because, in a 5-4 ruling, the Supreme Court struck down state laws segregating marriage by sex and sexuality (PDF). It’s a sweeping ruling with important consequences, and one that even a few years ago seemed unthinkable.

Judge Walker’s decision in 2010 had invalidated Proposition 8, a California referendum passed the same day Barack Obama was elected President. At the time, Barack Obama did not support permitting same sex marriage. In time, he declared that his position was “evolving.” As he evolved, his administration came to vigorously support extending marriage rights broadly, and he himself endorsed it. He was not alone in that evolution: polls show dramatic shifts in public sentiment, and many churches that initially resisted legal recognition of any same sex marriages now officiate such unions themselves.

And this, more than a passing reference to evolution, is what brings us within the scope of NCSE’s blog. In the late ’90s, it would have been easy to dismiss gay marriage as a matter which religion would necessarily and eternally oppose, just as evolution may seem to be. But within a generation, that equation has changed. The decision to uphold marriage equality was backed by Quakers, a coalition including the California Conference of Churches, rabbis, and Unitarians, Humanists, a coalition of more clergy and denominational groups than I can name, and many others (n.b.: those links all lead to PDFs).

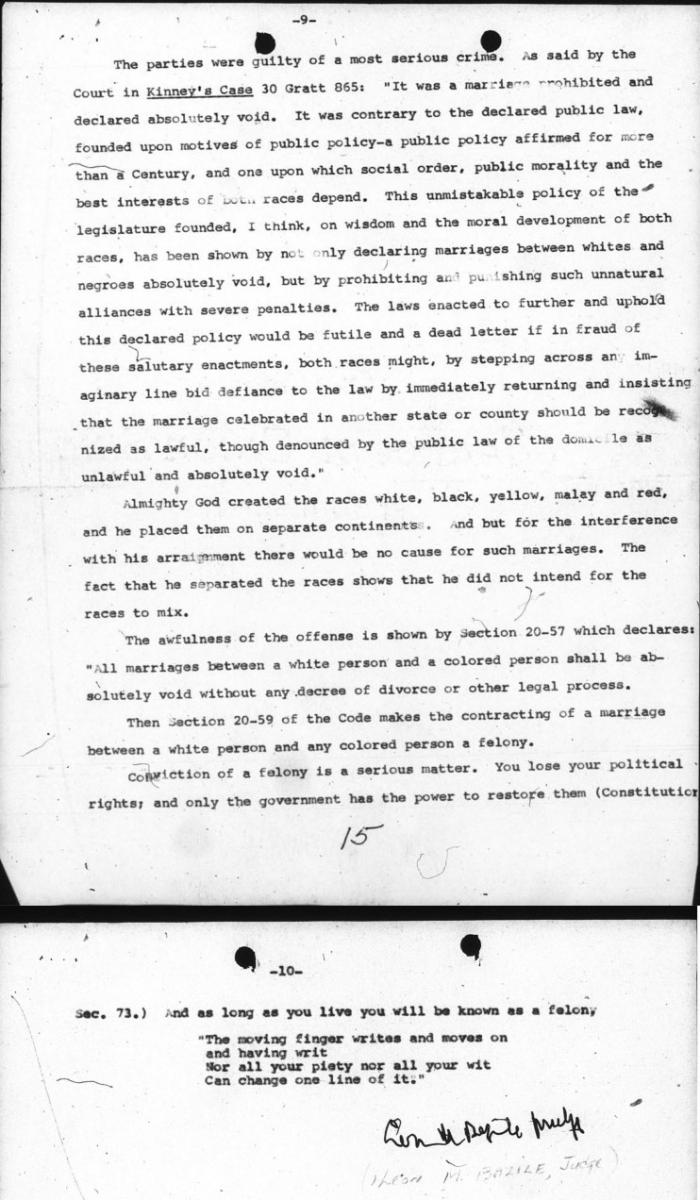

Indictment against Richard Loving and Mildred Jeter for the felony of marrying across racial lines. Click to embiggen. Via Library of Virginia.

Indictment against Richard Loving and Mildred Jeter for the felony of marrying across racial lines. Click to embiggen. Via Library of Virginia.Fifty years ago, racial segregation of marriage was seen as a religious matter, too. The judge who convicted Richard Loving and Mildred Jeter of the felony of miscegenation, a conviction which led to the aptly-named decision Loving v. Virginia, ruled not just based on the law, but on his creationist interpretation of the Bible:

Almighty God created the races white, black, yellow, malay and red, and he placed them on separate continents. And but for the interference with his arrangement there would be no cause for such marriages. The fact that he separated the races shows that he did not intend for the races to mix.

In the end, that judge’s way of reading the Bible did not survive constitutional scrutiny, and few churches remain which would regard interracial marriage as contrary to their own theology. Society evolved, religion evolved, and people evolved.

This is why it’s foolish to accept unchallenged the claim that religion (or some specific religion) must be at odds with science, or with evolution, or to claim that the fact that climate change and evolution are politically contentious now must mean they will be forever. Political evolution and religious evolution are as inevitable as biological evolution is scientifically established. With care and with energy, we can create those changes. That’s how marriage equality won, and it’s how we’ll win the climate battle, the battle against creationism, and the battle for science literacy.

And the marriage fight reminds us how those other battles must be won.

Love wins.

How and why love won is seen readily in the closing lines of Justice Kennedy’s stirring decision:

How and why love won is seen readily in the closing lines of Justice Kennedy’s stirring decision:

No union is more profound than marriage, for it embodies the highest ideals of love, fidelity, devotion, sacrifice, and family. In forming a marital union, two people become something greater than once they were. As some of the petitioners in these cases demonstrate, marriage embodies a love that may endure even past death. It would misunderstand these men and women to say they disrespect the idea of marriage. Their plea is that they do respect it, respect it so deeply that they seek to find its fulfillment for themselves. Their hope is not to be condemned to live in loneliness, excluded from one of civilization’s oldest institutions. They ask for equal dignity in the eyes of the law. The Constitution grants them that right. The judgment of the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit is reversed.

It is so ordered.

Same-sex marriage won because its advocates were standing up for what they loved, and even those who didn’t share that love could understand it. They relied on a fact embedded in many marriage services through a quote from 1 Corinthians:

If I speak in the tongues of men or of angels, but do not have love, I am only a resounding gong or a clanging cymbal. If I have the gift of prophecy and can fathom all mysteries and all knowledge, and if I have a faith that can move mountains, but do not have love, I am nothing. If I give all I possess to the poor and give over my body to hardship that I may boast, but do not have love, I gain nothing.

Love is patient, love is kind. It does not envy, it does not boast, it is not proud. It does not dishonor others, it is not self-seeking, it is not easily angered, it keeps no record of wrongs. Love does not delight in evil but rejoices with the truth. It always protects, always trusts, always hopes, always perseveres.

Love never fails. But where there are prophecies, they will cease; where there are tongues, they will be stilled; where there is knowledge, it will pass away. For we know in part and we prophesy in part, but when completeness comes, what is in part disappears. When I was a child, I talked like a child, I thought like a child, I reasoned like a child. When I became a man, I put the ways of childhood behind me. For now we see only a reflection as in a mirror; then we shall see face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I am fully known.

And now these three remain: faith, hope and love. But the greatest of these is love.

Despite its frequent use in wedding services, Paul was not writing mainly about romantic love here, any more than his reference to faith must be limited to religious faith. It’s the love of the good and right, the love for our fellow humans that gets activists up in the morning, the love for our world that drives environmental campaigners, and the love of truth and knowledge that brings scientists to the lab. When our work stems from that source, no power can stop it. Love wins.