“Greenhouse gases” and “the greenhouse effect” are terms used to describe some of the most basic concepts related to global warming. If students learn anything about climate change, they usually learn about these first. This is good in some ways, because these are the fundamental concepts in scientific explanations of how climate change works and why the earth is warming. But the specific metaphor here, comparing the Earth to a greenhouse with carbon dioxide and water vapor cast in the roles of panes of glass, has been criticized on the grounds that it may engender a misunderstanding of the science.

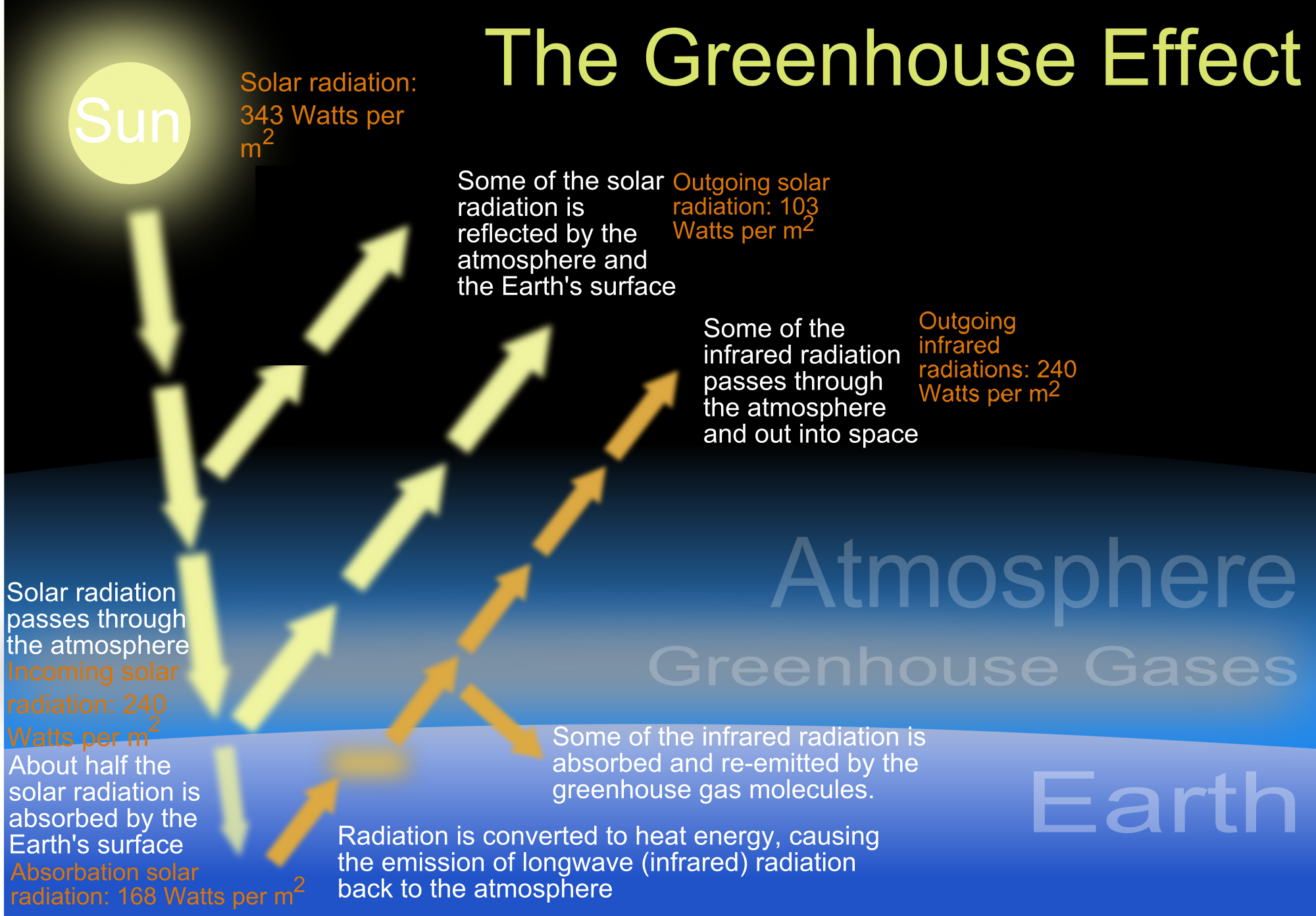

To evaluate the criticism, we need to start with a little background of what scientists mean when they use the term “greenhouse effect,” The image below (from Wikimedia Commons) nicely depicts the conventional model of the greenhouse effect. Solar radiation passes through the Earth’s atmosphere, hits the Earth, is converted to heat energy, and is radiated back to the atmosphere as infrared radiation. Some of that radiation is trapped by greenhouse gases and reradiated back down to the Earth, making the planet warm. Voilà.

Superficially, this seems very similar to a greenhouse: the greenhouse gases in the atmosphere keep it warm under them, just as the panes of glass in a greenhouse do. So what’s the problem?

Well, greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and water vapor are not panes of glass. The panes of glass in a greenhouse work by preventing convective cooling by reducing airflow. How do the greenhouse gases work?

The University Corporation for Atmospheric Research offers a good explanation of this:

There are several different types of greenhouse gases. The major ones are carbon dioxide, water vapor, methane, and nitrous oxide. These gas molecules all are made of three or more atoms. The atoms are held together loosely enough that they vibrate when they absorb heat. Eventually, the vibrating molecules release the radiation, which will likely be absorbed by another greenhouse gas molecule. This process keeps heat near the Earth’s surface.

Most of the gas in the atmosphere is nitrogen and oxygen – both of which are molecules made of two atoms. The atoms in these molecules are bound together tightly and unable to vibrate, so they cannot absorb heat and contribute to the greenhouse effect.

So a greenhouse for plants and the greenhouse effect for the Earth work in really very different ways. Using the same term for phenomena that are actually quite different could be confusing, especially for students who have labored to understand the differences among the forms of heat transfer.

Are we accidentally perpetuating misconceptions by using the “greenhouse” terminology? I posed this question to a number of colleagues in the climate education community. The feedback was interesting.

Some people defended the “greenhouse” terminology by arguing that it is an analogy, and analogies are meant to be suggestive, not exact. Some of them also appealed to the familiarity of the terminology: students are likely to have a good idea about what a greenhouse is like and how it works; wouldn’t it be foolish not to exploit that familiarity to explain how heat is trapped by greenhouse gases? These people agreed that the usefulness of the terminology outweighs the risk of the misconceptions it engenders.

On the other hand, other people argued that the terminology ought to be changed. One reason they cited was the importance of maintaining consistency across the sciences: if it is important in a physics classroom to distinguish among convection, radiation, and conduction as forms of heat transfer—which it is—then it should be important in a classroom where climate science is taught, too.

Another reason cited in favor of precision was the increasing importance of climate science. When the greenhouse effect and greenhouse gases were first identified as such, back in the nineteenth century, they were mainly under discussion by scientists who, presumably, were equipped to resist the misconception that the terminology might suggest. Now, in the early twenty-first century, it is crucial that climate science be accurately understood, not just by scientists but by the public in general and by students in particular.

What do you think? Do you think that “greenhouse gases” and “the greenhouse effect” are okay terms to keep using, even if they may perpetuate misconceptions? Or if you think other terms are needed, what would they be?