It's like the ultimate movie monster: invisible, slowly creeping until it rears its ugly head, suddenly lashing out, disguised as dramatic extreme events, growing more powerful and destructive over time. It strikes fear and terror in the populace, causing some to deny its existence and others to weep and wail as they try to warn their friends and neighbors.

It's like the ultimate movie monster: invisible, slowly creeping until it rears its ugly head, suddenly lashing out, disguised as dramatic extreme events, growing more powerful and destructive over time. It strikes fear and terror in the populace, causing some to deny its existence and others to weep and wail as they try to warn their friends and neighbors.

The clincher: the monster is fed by the people themselves, fueled by their daily activities, especially those involving burning buried solar energy. And the monster will be alive, thriving for generations to come, causing untold suffering for future humans and other species. Central casting couldn't come up with a more diabolical and deadly monstrosity.

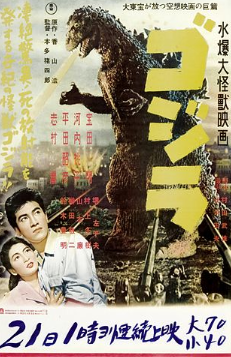

Ever since Mary Shelley wrote "Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus" in 1818, writers and, more recently, movie-makers have riffed on variations of the theme of monsters/threats that humans create, often as unintended consequences of their actions. Three generations ago, facing the monsterous potential of thermonuclear war, the monsters were The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms and Godzilla.

Today, the monster is climate change and related human impacts on the planet: biodiversity loss and extinctions, massive alteration of the Earth's system and cycles. And, according to a new Six Americas survey, this very real, very serious phenomenon is triggering many negative emotions. The majority of Americans who are already alarmed or concerned about global warming report feelings of being afraid, sad, angry, and disgusted thinking about it.

Even some who are dismissive of the human-produced monster admit to feeling angry and disgusted, likely because what they consider to be a hoax is being taken seriously by most Americans. The survey also found that while roughly one in four people don't think global warming is happening, some two thirds of Americans admit they'd like to know more about it, suggesting most are willing to be more climate literate.

But some say that the real monster isn't climate change. Claiming that scientists and activists deliberately gloss over probabilistic details, leave off error bars in their graphs, and otherwise take advantage of the public's shallow understanding of climate change, they say the Uncertainty Monster is what we should really worry about.

This approach is nothing new. For decades, efforts to sow doubt and uncertainty about climate science have succeeded in derailing and delaying efforts to confront it. Certainly, poorly communicated science, which is inherently complex, is an ongoing issue. And no doubt data literacy needs improving. But suggesting that the uncertainties of climate science are so significant and important that we can't really make informed decisions to reduce impacts and risks amounts to a diversionary or stall tactic. The Heartland Institute's contention that "science is never settled", as they suggested in the packet of materials recently sent to teachers is perhaps the most egregious example of the Uncertainty Monster running amok, but there is something of a cottage industry feeding that particular troll. Our friends at Skeptical Science helpfully suggest uncertainty is really an Ewok, and certainty of climate change is indeed the monster.

It's been said that in life the only certainties are death and taxes (unless of course you are a corporation with a good tax attorney, in which case you may be able to bypass the certainties mere mortals must contend with). But the monster of global climate change brings with it many certainties. Humans are a force of nature, especially the 20% of us who live large (relatively speaking) and are responsible for 80% of the fossil fuel emissions that are disrupting the Earth system, altering the climate and ecosystems that sustain life as we know it. And certainly we are woefully unprepared to address the changes that are already underway and will continue, whether quickly or slowly, over time.

Yes, there are and always will be uncertainties about climate change or any other risk we face. But just as the heros in the movies sooner or later have to confront the monster—and their own uncertainty—face to face, we, too, need to put aside our doubts and fears and look at the monster head-on.

In their book The Science and Politics of Global Climate Change: A Guide to the Debate, Andrew Dessler and Edward A. Parson compare managing human disruption of the climate system to "piloting a supertanker through dangerous waters," only there's no one at the wheel and the crew are below arguing whether there are rocks ahead or not. (There appears to be no irony intended in their choice of supertanker as metaphor for our current climate conundrum, but it is apt.)

Their solution?

In view of how long we have waited already, it is far more important to do something serious than to worry about getting the first step precisely right. Indeed, given the remaining uncertainties and political barriers to effective action, the first steps are sure to be imperfect, and will need to be assessed and adapted over time.

Given the facts that climate, energy, and related global change topics have long been missing or skimmed over in education and our overall literacy is low, the most serious thing we can do now is to promote much deeper and wider knowledge and know-how throughout society about the causes, effects, and risks of, and responses to, the monster we've created. While this is one monster that we may not completely banish, perhaps we can learn to somehow tame and live with it.