In part 1 of this post, I told you about the game-changing experience I had when I really started listening to how many of my students felt about my beloved language of science—i.e., that they hated it. I promised to tell you how people’s reaction to a hands-on climate change activity triggered another revelatory moment. At our Science Booster Club events in Iowa City about climate science and climate change, I’ve had an opportunity to observe people’s reactions to these topics up close and personal for the first time. Earlier in my life, I know I would not have been able to accept the depth of the negative emotions some people clearly experience when encountering this topic. I would have needed to bluster about it and come up with a reason why their emotional response was simply wrong. Perhaps, at some point, I would have needed to laugh at such people, to distance myself from them. Emotionally comfortable as that reaction may be for those of us who are frustrated by science denial, it doesn’t help solve the problem, does it?

Here’s what happened. Last week, for Halloween, the Iowa City Science Booster Club provided several hands-on climate change activities (specifically on sea level rise) for approximately 1300 people. A fair number of these people were children who were completely jumped up on candy. Of the adults, about 70% responded positively or with curiosity to information about climate change. Slightly less than half of the positive group had heard about the phenomenon and were interested to see it presented more clearly than they had in the past. Slightly more than half of the positive group had never before heard about sea level rise, were surprised by the information, and often took cards to learn more about climate change from our recommended sources.

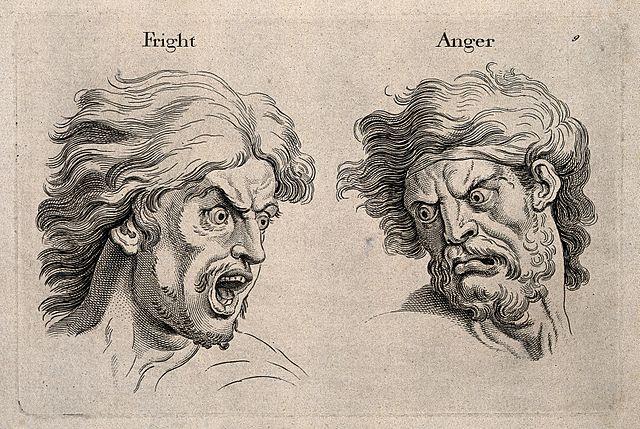

The other 30% reacted negatively to the information. Some of them quite negatively. This is not to say that all members of this group are people who actively engage in science denial. However, their reactions to information on climate change suggested profound psychological denial. Many people closed their eyes as they walked through the exhibit to avoid seeing these things. Some put their hands over their ears so they would not have to hear the presentations. Others wore expressions of despair, or of physical pain. Climate change had punched them in the gut.

Strong emotions, right? Very strong emotions! You can easily see how such profound psychological and emotional denial could find refuge in news sources and “think tanks” that cast doubt on the science of climate change in apparently intellectual language. But perhaps it also gives us some new ideas, another key we can use to reach out to this group of people. I suspect it will be important to understand what exactly about this information is hurting, frightening, or discouraging them, if we want to reach them. Frankly, I’m a ways off from that, but at least I’ve found a place to start.

A place to start is good news. And more good news is that the majority of adult guests who attended our event did experience it positively; did engage with the material, express interest, and often sought out more. Participants visiting from Florida and Louisiana expressed gratitude to see this problem that directly affects them presented in public. People talked about things they could do, and policies our country should take up, in order to combat the serious problem of sea level rise.

It is great that our current methods are reaching so many people. But climate change is a problem that involves everyone. We’ll continue working on new ways to reach people. With a new understanding of the emotional roots to this problem, I think we can brew up some different solutions.