The mass shooting in Orlando’s Pulse nightclub was the deadliest mass shooting in US history, singling out gay and Latin victims, and committed by a shooter who bought military hardware despite having been investigated for claiming ties to terrorist groups. It was also the 176th mass shooting of 2016 (or the 133rd, or something far less, depending what qualifies as a mass shooting), on only the 164th day of the year.

The mass shooting in Orlando’s Pulse nightclub was the deadliest mass shooting in US history, singling out gay and Latin victims, and committed by a shooter who bought military hardware despite having been investigated for claiming ties to terrorist groups. It was also the 176th mass shooting of 2016 (or the 133rd, or something far less, depending what qualifies as a mass shooting), on only the 164th day of the year.

Thankfully, mass shootings are outside the scope of NCSE’s daily work, but there’s an important lesson in this debate about the dangers of science denial. As I’ve noted before, one of the most blatant forms of science denial is the congressional ban on public health research into guns and gun violence. For two decades, the CDC and other federal research bodies have been restricted from funding research that would investigate fairly basic questions about mass shootings and what we can do about them, and federal law enforcement has been blocked from gathering data which might inform that research. Jay Dickey, the original author of the funding restriction, has since come out against it, telling the Huffington Post, “I wish we had started the proper research and kept it going all this time.”

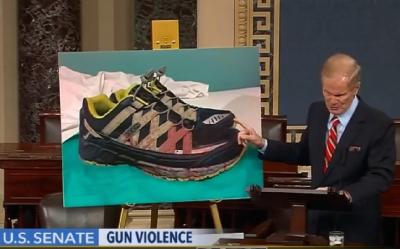

On Wednesday and into the early hours of this morning, Senate Democrats mounted a filibuster to demand a vote on measures to crack down on gun violence. Well into the 15-hour filibuster, Connecticut Senator Chris Murphy addressed the research ban, saying:

We’re not scientists.… When we get into the routine of deciding what’s worthy of research, bad things happen, whether it’s climate change or gun violence.

Worst of all, the ban on gun research doesn’t ban research in explicit terms. It’s a chilling effect due to sustained attacks on the science, including mischaracterizing science as politics. Ostensibly, the Dickey amendment only bans “advocacy” for gun control, even though government agencies aren’t allowed to fund advocacy anyway. But the 1996 bill containing the Dickey amendment also moved all the money from CDC’s injury prevention center to research on traumatic brain injury, and the move came after the NRA’s attacks on a 1993 study (funded by the CDC) finding that a gun in the home was associated with higher homicide risks. CDC leaders and public health researchers were able to connect those dots and understand the Dickey amendment as a ban on research. After the shooting at Sandy Hook, President Obama ordered that the administrative restrictions on research be lifted, but without funding authorization from Congress, there’s been little progress.

Vox’s Brad Plumer helpfully ran down some public health researchers and asked them what sorts of research they’d like to see funded, if Congress would lift the ban and allocate funds to this life-or-death issue. It should be noted that he didn’t have a large pool to draw on: the funding ban has meant that relatively few researchers are able to build a specialization on guns and public health in the US.

Among the questions the researchers want to be able to investigate:

- How are guns used? How often are they used to commit crimes, and how often to stop them? How often are they used for suicides, and how often are people injured in gun accidents?

- How many people are hurt by guns? It’s usually possible to locate information on people killed by guns, but other injuries may not turn up in records researchers can access.

- How do people get the guns used in crimes? The ATF and FBI are largely forbidden from even retaining the sorts of records that might let the chain of gun ownership be traced, even if loopholes didn’t permit private sales of guns without any federal or state records.

- What existing policies have the biggest effect on gun violence?

- What distinguishes mass shooting plans that are carried through from plans which are disrupted(either because of the shooter’s own volition, law enforcement response, or other deterrents by the target)?

As Plumer notes, there’s strong anecdotal evidence about some policies that might reduce gun violence. Connecticut responded to the Sandy Hook shooting by requiring all gun owners to obtain a license first; their gun homicide rate dropped 40%. Missouri repealed their requirement for gun purchasers to obtain a license, and saw a 23% hike in gun homicides. But without reliable data about gun sales and how guns move from legal sellers to criminal uses, it’s hard to definitively show that these policy changes (instead of unrelated social changes) drove the changes in gun homicide rates. But again, Congress has banned the ATF and FBI from maintaining the sort of database that might allow researchers to answer such questions.

America’s gun violence problem is an outlier relative to other nations, and research could show us why, and what we can do to make ourselves safer. The ideologically-driven ban on research has put the public at risk, and represents an ongoing attack on science as well.