I see that volume 20 of The Correspondence of Charles Darwin is out—and that I’m thanked in the front matter. Why? Thereby hangs a tale, which I told in the print supplement to Reports of the National Center for Science Education 2012;32:3;4–5. But I don’t mind telling it again here at the Science League of America blog.

Working at NCSE, I think that I probably answer as many recondite, recherché, and downright ridiculous questions as anybody, so I usually don’t seek extra opportunities to do so. But in late March 2012, I saw a blog post with the intriguing headline “One of our caricatures is missing!” The post continued:

Help! Can you identify a missing Darwin caricature? All we know is that it was called “The Young Darwinian” and was drawn by the American comic illustrator Thomas Francis Beard. A copy was sent to Darwin in 1872 by his friend Asa Gray but Darwin didn’t keep it.

And while that might not have impelled me to commit any time or energy, the fact that it was posted by Alison Pearn of the Darwin Correspondence Project did.

Thomas Henry Huxley once told Darwin, “You are the cheeriest letter-writer I know.” Cheery perhaps; diligent certainly. Even by the standards of Victorian England, when letter-writing flourished thanks to burgeoning literacy and the Penny Post, Darwin was a tireless correspondent. As David Quammen writes in The Reluctant Mr. Darwin (2006):

Self-sequestered inside both his home and his sense of frail health, he became very dependent on written correspondence and very disciplined in his use of it. He wrote letters for friendship, letters for business, letters for love (to his “dear old Titty” or his “dear Mammy,” as he variously called Emma, when they were apart), letters for good deeds and scientific politicking, letters asking parental advice and (later, with his sons away) giving it, letters for the sheer joy of prattle, and most of all, letters seeking scientific information. He peppered friends, acquaintances, and strangers with questions, requests for data, little assignments of experimentation that they might perform for him if, ahem, it wasn’t too much trouble.

It is estimated that over his life there were more than fifteen thousand letters to and from Darwin. (It’s unnerving to think what he might have done with e-mail or Twitter at his disposal.)

Founded in 1974 by Frederick Burkhardt, the Darwin Correspondence Project is engaged in the task of locating, researching, and publishing all of the extant Darwin correspondence. It’s been described as the greatest editorial project in the history of science and one of the major international scholarly projects of the past half-century. The Project is publishing Darwin’s letters in chronological order—volume 19, covering the year 1871, was the latest volume in print when Pearn posted on its blog—and also steadily adding to its website, which currently contains complete transcripts of all known letters Darwin wrote and received up to the year 1868.

Wanting to help, and having a few moments to spare, I thought a little about Pearn’s request for assistance in identifying the caricature. In her post, she indicated what luck the Project had so far:

We think it was probably drawn in 1871 or 1872 in response to Darwin’s book Descent of Man. Beard was a prolific artist who worked for a number of US magazines and newspapers, including Phunny Phellow, Wild Oats, Budget of Fun, Jolly Joker, Comic Monthly, and Harper’s Weekly.

Well, I thought, if it were as easy as using Google to search for “Thomas Francis Beard AND Darwin” or “Beard AND ‘The Young Darwinian’”, then the Project would already have found it. So perhaps Gray made a trivial mistake in his letter to Darwin: maybe the caricature was entitled “Darwin as a Youth,” say, or maybe the artist was a different Beard. In fact, Gray’s letter, as quoted by Pearn, referred only to “Beard,” and although Thomas Francis Beard was identified as the artist in Frederick Burkhardt and Sydney Smith’s A Calendar of the Correspondence of Charles Darwin, perhaps that was a misidentification, too.

That turned out to be the right approach. A few searches with Google for “Beard AND Darwin*”—where the asterisk indicates that any word beginning with “Darwin” is acceptable—swiftly revealed that William Holbrook Beard, the uncle of Thomas Francis Beard, painted “The Youthful Darwin Expounding His Theories,” a photograph of which was exhibited at the Century Club in New York in 1871, and prints of which were published by the American Photoplate Printing Company in the same year. Beard was famous for his scenes of animals satirizing human behavior: prints of his painting of “The Bulls and Bears in the Market” (1879), showing the titular animals running amok in Wall Street, are still available. And he was interested in, if skeptical of, evolution, too: his 1891 “Discovery of Adam,” for example, shows a group of clothed and civilized monkeys bewildered at their discovery that their ancestor, Adam, was in fact a tortoise.

Now armed with a name and title, I was able to discover that the original “The Youthful Darwin” is now in the possession of the American Museum of Natural History, having been acquired—I don’t know when—by its longtime head Henry Fairfield Osborn. But I couldn’t find a picture of “The Youthful Darwin” at the AMNH website or anywhere else on-line, and although I found a few sources—a catalog of a Beard exhibit in a New York gallery; a review of the same exhibit; a magazine article about Beard—that were likely to describe it in detail, none of them was on-line, either. And desirous though I was to help, I wasn’t really willing to make a special trip to a large enough library to be able to find those sources. So the identification was, if plausible, still not quite conclusive.

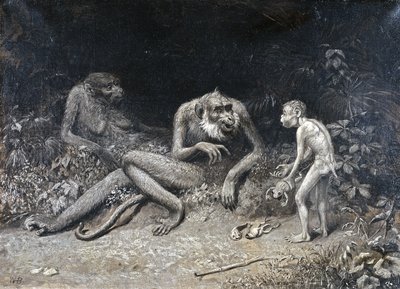

I e-mailed Pearn with my findings, and she agreed with my suggestion that Gray might well have been talking about “The Youthful Darwin.” I was gratified to see, a few weeks later, a follow-up post by her announcing “we found the right image just in time to include it in the next volume of the Correspondence of Charles Darwin (vol. 20) which is about to go to press” and thanking me as well as NCSE member Michael Barton, who also worked on the mystery. Accompanying her post was a small image, provided by the AMNH, of “The Youthful Darwin,” showing, as Pearn writes, “a young humanoid with a nicely vestigial tail, showing a pair of sceptical (and slightly amused) older apes a series of organisms from a fish to an amphibian.”

This wasn’t the most important, or the most extensive, bit of research ever conducted at NCSE, of course. (On both counts, that honor would probably go to the archival work that Nick Matzke and Jessica Moran did in 2004 and 2005, helping to establish the creationist roots of Of Pandas and People and leading to the verdict in Kitzmiller v. Dover.) But it was a pleasure and a privilege for me to be able to contribute, if only in a small way, to such a worthy scholarly endeavor as the Darwin Correspondence Project!

Had you been a member in good standing of NCSE when the foregoing article was published, you wouldn’t have had to wait to read it on the Science League of America blog. So why not take a moment to join NCSE, or renew your membership, right now? It’s only $35, $40 for foreign addresses, and $700 for a lifetime membership.