What do we know about F. E. Dean? He studied under Winterton Curtis at the University of Missouri; he was the superintendent of the Fort Sumner, New Mexico, public schools for a few years until he was forced to resign in 1922 when he challenged the school board’s adoption of a policy prohibiting the teaching of evolution (see part 4), and he had something of a gift for invective (see part 3). His plight occasioned statements from both William Bateson (see part 2) and Woodrow Wilson (see part 1), thanks to Curtis, who then thriftly used them in the Scopes trial in 1925. In November 1922, when he sought Bateson’s help, Curtis told him that Dean hadn’t found a new position yet. As A. G. Cock wrote in his 1989 article in the Journal of Heredity, which heralded Dean as a hero who deserves to be remembered along with John Thomas Scopes, “at least as far as the sources available to me disclose, he disappears from the record.”

I mentioned earlier (part 2) that it’s not helpful just to use Google to search for “F. E. Dean,” and none of the documents from the Bateson archive said what his initials stood for. (Francis Ernest? Frederick Edward? Fabio Englebert?) I won’t bore you with the twists and turns of my search. The line of investigation that was finally fruitful was as follows. Searching a legal database for “F. E. Dean,” I discovered a case decided by the Arizona Supreme Court in 1940. Someone named F. E. Dean was appealing a lower court’s decision about a dispute over his pension after he retired from the post of Superintendent of School District No. 2 in Coconino County. (He lost.) A school superintendent in the Southwest with the right name: good. The court decision mentioned that he was over sixty years old in 1940, so he would have been born before 1880 and he would have been over forty-two years old in 1922. Was this the right Dean?

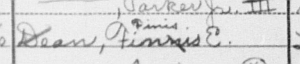

Well, there’s a way to investigate such matters. Off to the U.S. Census for 1940 I went. Poring through the records for Coconino County, Arizona, I discovered, eventually, a line (see above) with “Dean, Finnis [with “Finis” written above] E.,” with his age indicated as 62 (which is not quite right, actually), his place of birth indicated as Missouri, and his occupation indicated as public school teacher. Bingo! Frankly, I would never have thought of Finis as a plausible first name for F. E. Dean. (It was, in fact, Jefferson Davis’s rarely used middle name, reputedly because he was expected to be the last of his parents’ offspring, but there’s a different reason, I suspect, that F. E. Dean was named Finis, which I will mention shortly.) With the first name of Finis in hand, I was able to find Dean’s obituary in the Arizona Independent Republic for April 11, 1941, and to reconstruct the outline of his life on the basis of the obituary and a few further searches.

Finis Ewing Dean—his obituary renders his middle name as “Ewins,” but other sources indicate “Ewing,” and it seems plausible that he was named for Finis Ewing, a prominent clergyman in the Second Great Awakening who founded the Cumberland Presbyterian denomination in 1810—was born on a farm outside Carrollton, Missouri, on April 22, 1876. At the age of eighteen, he started teaching. Later, by 1905 at the latest, he began to attend the University of Missouri, where he presumably befriended Winterton Curtis. He was not finished until 1915, when he graduated with the degrees of bachelor of arts and bachelor of science. His progress was slow or sporadic because he was working; he is listed as a school principal and a newspaper publisher in Palisade, Colorado, in 1905. He later earned a master's of arts degree from the University of Colorado in 1923, with a thesis on “A Study of Religious Mysticism.”

From about 1920 to 1922, of course, Dean was the superintendent of schools in Fort Sumner, New Mexico. In late 1922 or 1923, he moved to Arizona, where he taught in St. David for two years, served as a principal in Benson for seven years, and served as a superintendent of schools in Williams for seven years. He was discharged from the latter job in 1939, apparently because the district lacked confidence in his physical ability to do the job. He successfully sued the district for breach of contract, but was unsuccessful in securing a pension for disability for the 1939–1940 school year; the Arizona Supreme Court reasoned that by suing the district for breach of contract, he was implicitly conceding that he was not disabled. He then engaged in the real estate business and operated a bookstore. He died on April 9, 1941, owing to complications after a fall in which he broke a left thigh bone.

There’s more to be discovered about Dean’s life, clearly. Even on the basis of what’s available, though, I’m inclined partly to dispute Cock’s judgment that “Dean deserves to be remembered, along with John T. Scopes, as an early hero of the continuing fight for the right to teach evolution in U.S. schools.” Scopes, in Cock’s view, was “genuinely a hero, but not in any sense a victim or martyr”; I agree. But while Dean was in a sense a victim, he wasn’t a martyr. Rather than having stayed and fought it out, he allowed himself to be shoved off stage. As a result, he never was able to play the role that Scopes played or to become the iconic figure that Scopes became: in short, he's not a heroic figure. Of course, I don’t fault Dean for not fighting it out; who among us can say with certainty that he or she would have the courage to do so? But I don’t place him alongside Scopes. I agree with Cock, though, that Dean deserves to be remembered, and perhaps by now I’ve helped to ensure that he will be!