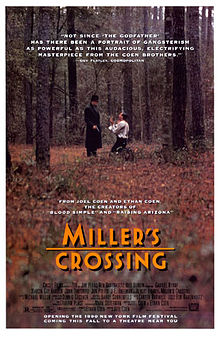

In Miller’s Crossing (1990), one of my favorite movies of all time, the gang boss Johnny Caspar murders his henchman Eddie Dane, on the mistaken assumption (fostered by Tom Reagan) that Dane double-crossed him, and remarks by way of explanation, “I had a theory about this son of a bitch!” In “Speculatin’ about Hypotheses,” I gratuitously quoted Miller’s Crossing before I began to criticize the National Academy of Sciences definition of “hypothesis,” so I may as well take the opportunity to address its definition of “theory” now.

According to the definition of “theory” offered in Teaching about Evolution and the Nature of Science (1998), a theory is “a well-substantiated explanation of some aspect of the natural world.” Similarly, in Science, Evolution, and Creationism (2008), “theory” is defined as “a comprehensive explanation of some aspect of nature that is supported by a vast body of evidence.” I am happy enough with the idea that a theory seeks to explain “some aspect of the natural world,” although I think that the idea that a theory is “comprehensive,” in the latter definition, is important.

It’s the phrases “well-substantiated” and “supported by a vast body of evidence” in these definitions of “theory” that trouble me. Certainly it’s a desideratum in a theory for it to be well-substantiated and supported by a vast body of evidence. Certainly the theories that are generally accepted in contemporary science are well-substantiated and supported by a vast body of evidence. And certainly the topic of these publications—evolution—is well-substantiated and supported by a vast body of evidence.

For all that, I don’t think that it’s a necessity for a theory to be well-substantiated and supported by a vast body of evidence. Consider nascent theories, like string theory (or evolutionary theory circa 1859), and obsolete theories, like caloric theory. As far as I understand the situation, a vast body of evidence is not presently thought to support these theories. Are they therefore not presently theories? Or are they—as I would urge—theories simply in virtue of the fact that they aspire to offer systematic explanations of ranges of natural phenomena?

(Here again I might invoke the Oxford English Dictionary, according to which a theory, in the relevant sense given, is, “A scheme or system of ideas or statements held as an explanation or account of a group of facts or phenomena; a hypothesis that has been confirmed or established by observation or experiment, and is propounded or accepted as accounting for the known facts; a statement of what are held to be the general laws, principles, or causes of something known or observed.” Alas, only the first and third of these clauses clearly support my view.)

Of course, it would be possible to bite the bullet here, to say that string theory is just a wannabe and that caloric theory is just a has-been, but neither is, strictly speaking, a theory. But it’s hard to see what advantages there are to speaking in such a way as to make “this theory is supported by the evidence” a tautology and “that theory is not supported by the evidence” a contradiction in terms. It is noteworthy that Teaching about Evolution and the Nature of Science refers to “the geocentric theory,” which should be verboten by its own definition of “theory.”

The Understanding Science web site more or less agrees with me: “In science, a broad, natural explanation for a wide range of phenomena. Theories are concise, coherent, systematic, predictive, and broadly applicable, often integrating and generalizing many hypotheses. [I’d say that these are desiderata for, not definitive of, theories, however.] Theories accepted by the scientific community are generally strongly supported by many different lines of evidence—but even theories may be modified or overturned if warranted by new evidence and perspectives.”

I suspect that the authors of the National Academy of Sciences definitions may have just overreacted to the familiar creationist charge that evolution is “just a theory.” Unpacked, the charge is that evolution is a matter of conjecture or speculation without any evidence behind it, and it’s all too common a refrain in the creationist literature. It wouldn’t be surprising if the authors succumbed to the temptation to define “theory” in such a way that a theory is necessarily, automatically, by definition, supported by the evidence.

As a reaction to the creationist charge, that wouldn’t really help, of course, since a creationist might accede to the definition but insist that evolution then isn’t even a theory. I’m not just speculating here, either. Witness the young-earth creationist ministry Answers in Genesis, which declares, “Although some Christians have attacked evolution as ‘just a theory,’ that would be raising Darwin’s idea to a level it doesn’t deserve,” relying on a definition of “theory” more or less like the National Academy of Sciences definition.

(Worrying about the National Academy of Sciences definition of “theory” is a little bit of a hobbyhorse with me, I should admit. I last mounted it when I was discussing (PDF) the response of the Kentucky Department of Education to comments from the public on the Next Generation Science Standards: “It is also praiseworthy that the KDE avoided repeating a faulty response from the National Academy of Sciences,” I wrote, citing the same examples of string theory and caloric theory. But what’s a blog for if not obsessively riding hobbyhorses?)

So on neither “hypothesis” nor “theory” am I able to agree with the National Academy of Science definitions. But let me accentuate the positive: the flaws in the definitions of “hypothesis” and “theory” are readily resolved, and pale in comparison to the virtues of the authoritative yet accessible presentations of evolution to be found in Teaching about Evolution and the Nature of Science and Science, Evolution, and Creationism. And really, what’s most important in evolution education is not attaching the correct philosophical labels but understanding the science.