Science frequently challenges our intuitive understanding of the world. Even as an adult, I am constantly confronted with new scientific advancements and discoveries that don’t always line up with my preconceived notions. Such ideas are considered counterintuitive because they present themselves in ways that are counter to one's intuitive notions or “gut feelings.”

Counterintuitive concepts have been challenging how we understand the world for ages. As early as the sixth century B.C., the idea that the sun, moon, stars, and visible planets all revolved around the Earth was commonplace. This idea is still shared widely by young children today. When asked to point to Earth when shown an image of the solar system, 69% of American first graders pointed to the sun. However, as students got older and more educated, they shift from this geocentric view (that Earth is the center of the solar system) to a more heliocentric one (that the sun is the center of the solar system).

One of the most challenging and powerful counterintuitive concepts, the theory of evolution by natural selection, also happens to be one of the most rewarding; its ability to explain the complexity of life on Earth, and even (to a certain extent) human nature, is unprecedented. Despite its importance, however, evolution is often labeled as “controversial” and has not achieved widespread acceptance in the United States. Reports suggest that only 60% of Americans believe that “humans and other living things have evolved over time,” and even then only 32% of this group state that evolution is due to “natural processes such as natural selection.” Unwillingness to accept evolution has complex roots in religious and political identification, which I won’t go into here. What I will discuss is how recent cognitive research adds insights into our problem with widespread acceptance of evolution and suggestions on how to improve it.

First, let’s admit that evolution is indeed counterintuitive. The idea that all life (from bananas to blue whales) is related and has resulted from billions of years of evolution beginning with single-celled ancestors is not exactly a superficial or simple idea—but it is correct. So how, then, can we improve an individual’s chances of coming to accept it?

Recent studies lead by Deborah Kelemen strongly suggests that if you start presenting children with counterintuitive concept like evolution early they develop a greater facility for applying analytical thinking when they are presented with something counterintuitive. This strategy may help prevent misconceptions about such concepts from becoming rooted in their minds.

To begin to understand this conclusion, it is important to consider the biases present in how humans view the natural world. For example, regardless of their religious beliefs, adults, and especially children, are inclined to see design and purpose everywhere. Kelemen has documented this way of thinking, termed “promiscuous teleology,” in children as young as preschool, though it is worth noting that teleology—the idea that something exists for a purpose—is an inclination we all share. Children, however, are much more indiscriminate and casual in their application of teleology to the world than adults, ascribing purpose to all kinds of entities—objects, living and nonliving things, and their properties.

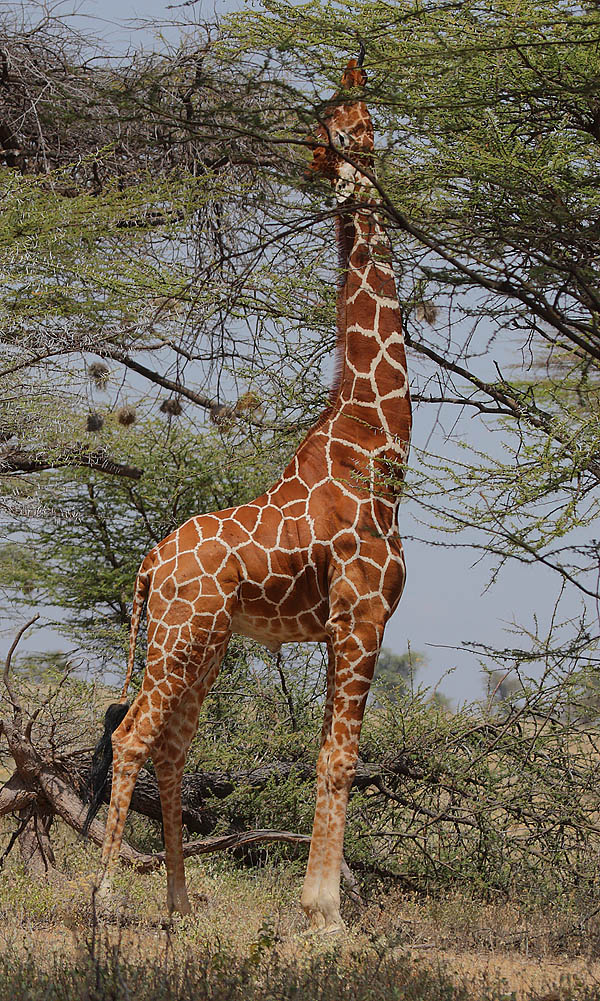

Kelemen has found, for example, that when children were asked “Why are rocks pointy?” they responded with purposeful statements like “Rocks are jagged so animals can scratch themselves.” By elementary school (ages 6–10), kids begin to develop their own “folk biology” theories (that is, how people classify and reason about the organic world) about the world around them, giving explanations for biological facts in terms of intention and design. This can be seen in children’s design-driven descriptions for the purpose for a giraffe’s long neck—so it can reach the leaves at the top of the trees. This suggests that believing in creationism may be a very natural tendency, and that introducing evolutionary frameworks in childhood may help lay the groundwork for balancing promiscuous teleology with analytical thinking.

To see whether young children could understand the mechanism of natural selection before the alternative intentional-design ideas had fully set in, Dr. Kelemen and colleagues presented five- to eight-year-olds with a ten-page picture book that illustrated an example of natural selection with a fictional population of animals called “pilosas.” In the book, the pilosas are described as insect-eating mammals, some with thick trunks and some with thin. The children are then told about a sudden shift in climate that drives all of the insects into narrow underground tunnels. Because of this, the thin-trunked pilosas were the only ones to be able to reach the insects, causing those with thick trunks to die off. Therefore, the next generation of pilosas all had thin trunks.

To see whether young children could understand the mechanism of natural selection before the alternative intentional-design ideas had fully set in, Dr. Kelemen and colleagues presented five- to eight-year-olds with a ten-page picture book that illustrated an example of natural selection with a fictional population of animals called “pilosas.” In the book, the pilosas are described as insect-eating mammals, some with thick trunks and some with thin. The children are then told about a sudden shift in climate that drives all of the insects into narrow underground tunnels. Because of this, the thin-trunked pilosas were the only ones to be able to reach the insects, causing those with thick trunks to die off. Therefore, the next generation of pilosas all had thin trunks.

Before they heard this story, the children were asked to explain why a different group of fictional animals had a particular trait. Most of them, consistent with previous research, gave explanations based on intentional design. However, after they heard the “pilosas” story, the answers they gave were very different. They began to understand the basic tenets of the theory of evolution by natural selection. Even three months later, their understanding and analytical explanations persisted.

This is great news! If we start teaching evolution sooner, with age-appropriate examples, we’ll be less likely to have students reaching high school with misconceptions firmly entrenched. Problem solved, right? Not so fast, additional research—to be described in part 2—suggests that differences in cognitive style may also get in the way of understanding and accepting evolution.

Ashle Bailey-Gilreath holds a Master’s degree in Cognition and Culture from the Institute of Cognition and Culture at Queen’s University Belfast. She currently works as a Research Assistant for both the Institute of Cognitive and Evolutionary Anthropology at the University of Oxford and the Institute of Cognition and Culture. She is also the Web and Social Media Coordinator for the Evolution Institute and This View of Life. This piece was adapted from an earlier version written for Learning & the Brain.