Each year, in May, I have the distinct pleasure of serving as a volunteer judge for the Massachusetts State Science & Engineering Fair (MSSEF). The event, which takes place at MIT, is one of my favorite days of the year. I spend most of my days alone in my home office immersed in some of the less appealing aspects of science education—the politics, the standards, and of course, the denialism that worms its way into far too many classrooms. MSSEF is like a booster shot of morale—an inoculation against despair and frustration. Nothing can make you feel better than talking to bright, motivated, and creative high school science students! This year’s fair, which took place on May 1, was the most outstanding one yet for me. Each of the six projects I judged were stellar—one both figuratively and literally.

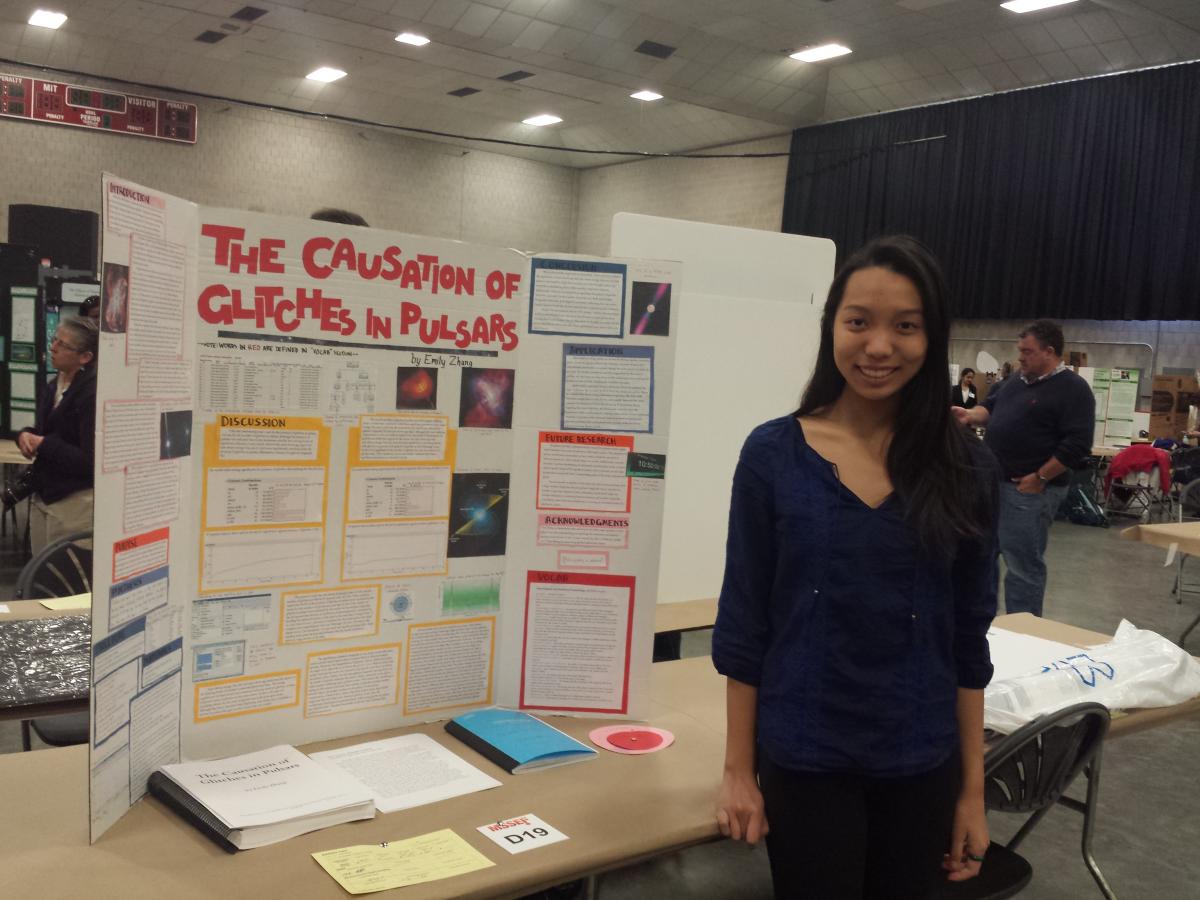

When I walked up to 15-year-old Emily Zhang’s poster, “The Causation of Glitches in Pulsars,” I was wary. Why? Because—I confess—I don’t get space. Space, along with electromagnetism (I consider my radio the closest thing to magic in my day-to-day life), is the big science topic that just seems to be beyond my capacity to figure out. I can answer basic questions about space correctly, but I just can’t internalize the concepts. When I saw The Martian, I knew, intellectually, that it takes ten months to get to Mars, but in my head, I kept thinking, “why the heck is this taking so long? It’s right there! It’s, like, the next planet over!” Thus I was in a bit of a panic as I approached Emily’s station. I needn’t have feared. From moment one, Emily had my rapt attention. She was clear, engaging, and accessible without being either pedantic or patronizing. After about a half hour with her, not only did I know about pulsar glitches, but I also knew that I’d met a student with a natural talent for science communication.

When I walked up to 15-year-old Emily Zhang’s poster, “The Causation of Glitches in Pulsars,” I was wary. Why? Because—I confess—I don’t get space. Space, along with electromagnetism (I consider my radio the closest thing to magic in my day-to-day life), is the big science topic that just seems to be beyond my capacity to figure out. I can answer basic questions about space correctly, but I just can’t internalize the concepts. When I saw The Martian, I knew, intellectually, that it takes ten months to get to Mars, but in my head, I kept thinking, “why the heck is this taking so long? It’s right there! It’s, like, the next planet over!” Thus I was in a bit of a panic as I approached Emily’s station. I needn’t have feared. From moment one, Emily had my rapt attention. She was clear, engaging, and accessible without being either pedantic or patronizing. After about a half hour with her, not only did I know about pulsar glitches, but I also knew that I’d met a student with a natural talent for science communication.

Although the awards are handed out the weekend of the fair, it takes months for MSSEF to release the winners list to the public. I checked back periodically, but it wasn’t until August that I found out that Emily had taken the top prize. I was absolutely delighted and wrote an e-mail to the science department chair at Lexington High School in Lexington, Massachusetts, to offer my congratulations and to request that my contact information be passed along. Emily, now a junior, wrote me back in September and agreed to be interviewed for the blog.

Stephanie Keep: Tell me about how you came to be at the state science fair. How did you think up your project and what other fairs had you won to get there?

Emily Zhang: Last year, my sophomore year, I was taking AP Biology. Participation in the science fair was required of all students taking AP science classes in my high school—but the topics were up to us. I was looking for an exciting project that would keep me absorbed for a long time. I’ve always loved astronomy, so I talked through my ideas with the astronomy teacher at my school (Kelly Kilts). Although some topics had already been extensively researched, I found that pulsars were relatively unexplained, and decided to make them my focus! One of the categories in an on-line pulsar database was “Number of glitches,” which completely mystified both Ms. Kilts and me. As I looked more into what glitches were—and realized there wasn’t that much research out there—I grew more and more excited about them!

After finishing my project, I attended my giant school science fair (over 200 projects) in February. I advanced from there to the regional fair at Somerville, then to the state fair.

SK: Did you ever think you’d win? How’d that feel?

EZ: I wasn’t even expecting to go beyond the school science fair, to be honest! Getting first place at the state fair was a huge, huge surprise. I was grinning like crazy.

EZ: I wasn’t even expecting to go beyond the school science fair, to be honest! Getting first place at the state fair was a huge, huge surprise. I was grinning like crazy.

SK: One of the things that impressed me most about your project was how genuine and self-guided it was. Were you intimidated by projects that had been done in professional lab settings?

EZ: I admit, those projects were scary at first. However, I had some friends who explained their intimidatingly-named projects to me, and I realized that if you substitute familiar words in place of the fancy scientific names (a common one was “fruit flies” instead of “Drosophila”), the projects become much more understandable and much less daunting.

For my project, I wanted to avoid a lab setting because I was a little reluctant to keep my research in some kind of set space. I’m very happy with the independence I had in doing an astronomy project. Working with a computer, paper, and pen gave me the freedom to work on my project whenever I could and implement ideas as soon as I thought of them!

SK: An NSF-funded study is under way to assess whether science fairs are “worth” the time and cost. I read that story with dismay because I love going to fairs, but I know that for many students and their parents, the science fair is considered a major and stressful hassle. What suggestions would you make to teachers trying to inspire their students, and to make fairs a more positive experience for everyone?

EZ: Many students used to complain about the science fair being boring because they were only allowed to do a certain type of project (often biology) by their teachers even though they didn’t find it interesting. I think choosing a topic is one of the most important parts of science fair. Once the line between science fair work and free time blurs, you know you’ve picked the right topic. I think teachers should really emphasize that point, and be more involved in the selection process to help kids find something they truly enjoy.

My school (Lexington High School) used to require students in AP science classes to submit a science fair project. That policy was changed this year, and I think it’s for the better. This year, the fair is optional, and students of any level science class can do a project! Anyone who participates receives school credit.

SK: You are probably the best communicator I have ever come across at the fair. Do you have any idea how rare it is to find a good science communicator? How did you come by those skills at such a young age?

EZ: Thank you so, so much! I’m honestly not sure—it may be because I’ve always been encouraged to share and explain my ideas at home, especially since so many of my experiences growing up in America (and the twenty-first century) are new to my parents. [Emily’s parents emigrated from China to attend graduate school in the United States.] Along with this at-home practice, I genuinely love speaking to others, and I try to let that enthusiasm show in my conversations.

SK: What tips can you offer scientists? (They need tips!)

EZ: I think the most important part is using clear, easy-to-understand language and explaining everything. (Even if I thought a concept I used in my project was well-known, I still explained it as a refresher and to help the listener find their footing in the presentation). I definitely used analogies, as well as lots and lots of relatable examples. I also varied my tone and spoke at different rates to draw attention to certain points, which may seem insignificant, but I think nothing kills a presentation quicker than a monotone.

EZ: I think the most important part is using clear, easy-to-understand language and explaining everything. (Even if I thought a concept I used in my project was well-known, I still explained it as a refresher and to help the listener find their footing in the presentation). I definitely used analogies, as well as lots and lots of relatable examples. I also varied my tone and spoke at different rates to draw attention to certain points, which may seem insignificant, but I think nothing kills a presentation quicker than a monotone.

SK: Tell me how your teachers have influenced you. Is there a teacher or other educator that has served as a mentor?

EZ: I’m really lucky to have had passionate and dedicated teachers throughout my life. The best teachers I’ve had were creative enough to utilize their students’ interests in teaching them concepts, and flexible enough to go beyond the class lessons for their students.

For my science fair project, Ms. Kilts was my mentor, and her knowledge of astronomy and the research process was invaluable. She gave me so much freedom in my project while also helping me orient myself at the start of the process and home in on a topic.

SK: What do you want to be “when you grow up?”

EZ: All I know for sure is that I want to do something that involves working with people and traveling!

SK: Will I see you at the fair this year? More pulsars?

EZ: Hopefully! I was actually thinking about a partner project this year in order to do more in-depth research. I may continue with astronomy, or I might try engineering!

Postscript: Emily just told me that through the Massachusetts Junior Academy of Science, a competitive symposium that took place last weekend, she’s been invited to present her science fair project at a conference in Washington D.C. this February! So, according to Emily, “Pulsars will be sticking with me for a little longer, it seems :)”

Are you a teacher and want to tell us about an amazing free resource? Do you have an idea for a Misconception Monday or other type of post? Have a fossil to share? See some good or bad examples of science communication lately? Drop me an email or shoot me a tweet @keeps3.