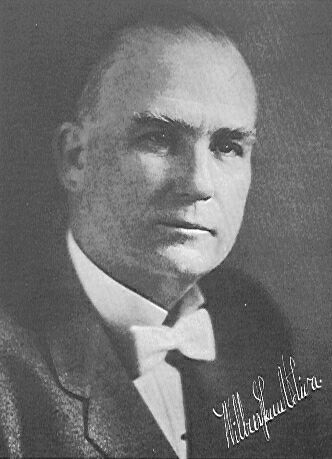

Perhaps I’m channeling Robert J. Schadewald, a former president of NCSE’s board of directors who was a scholar of flat-earthery, but I can’t seem to help myself. While I was reading through old newspapers looking for information about Wilbur Glenn Voliva, the flat-earther who hoped to be called to testify in the Scopes trial (see “Voliva!”), I stumbled across the following challenge in the Ogden Standard-Examiner of September 10, 1922, attributed to Voliva:

1—Why is it that stars are visible in broad daylight just by looking down a well?

2—Why is it that you see stars when you get a severe blow on the head?

3—If you were to dig a shaft straight down through the earth and you were to go down that shaft feet first, at what point during your descent would you have to turn end for end in order to come up in the antipodes right side up, and at what point would the blood rush to your head?

The third of these questions, of course, is supposed to be the doozy, the humdinger, the sockdologer: the question that exposes, for once and for all, the intellectual bankruptcy of the round-earth dogma. The article explains, “One of Voliva’s apostles has answered the two leading questions satisfactorily. No one has answered the third.” Well, honestly, I hesitate to place myself in the same intellectual caliber as Voliva’s apostles, but I think that I can take a stab at answering all three.

Why is it that stars are visible in broad daylight just by looking down a well? They aren’t. If you look down a well, you won’t see much of anything—the walls of the well, maybe the chain of the bucket, perhaps the surface of the water, conceivably the reflection of the sun (which is a star) on the surface of the water. But I’m sure that either Voliva or the Standard-Examiner garbled the question. It should be, Why is it that stars are visible in broad daylight just by looking up a well? Here, too, the answer is that they aren’t, but the misconception that they are—that the stars are visible in daylight when the observer is shaded from the brightness of the sky by the walls of a well or a chimney—is widespread and of long standing. In antiquity, both Aristotle and Pliny mentioned the (supposed) phenomenon, and both Charles Dickens (Hard Times) and Rudyard Kipling (“The Song of the Banjo”) used it for literary effect in the nineteenth century. But theory and experiment and even Snopes.com confirm that the stars aren’t visible in such conditions.

Why is it that you see stars when you get a severe blow on the head? Well, it’s not stars—huge luminous spheres of plasma—that you see. Really, you’re not seeing anything, strictly speaking: rather, you’re having the experience of seeing light without light actually entering your eye. The technical name for such phenomena is phosphenes. (I am charmed to discover that the term “phosphene” was coined by a French doctor named Jean Baptiste Henri Savigny, who, earlier in his career, was a surgeon on board the Medusa, the French frigate wrecked in 1816 and immortalized by Théodore Géricault in “The Raft of the Medusa.”) Phosphenes can be the product of not only a blow on the head but also pressure on the retina (as caused when you rub your eyes), sneezing or coughing, or even a more serious condition, like incipient retinal detachment, so consult your doctor or ophthalmologist if they interfere with your vision or if they’re persistent. Don’t consult your astronomer, especially if he or she is a flat-earther.

If you were to dig a shaft straight down through the earth …, at what point during your descent would you have to turn end for end in order to come up in the antipodes right side up, and at what point would the blood rush to your head? There are two questions here. The answer to the former question depends on how fast you can turn yourself end for end, obviously. Assuming that the tunnel is through the center of the earth and ignoring practical considerations like air resistance and blazing heat and tunnel collapse, the trip would take somewhere between thirty and sixty minutes, according to the physicist Rhett Allain: time enough even for the most ungainly of us to execute a somersault, I would think. The answer to the latter question is, simply, afterward if at all. While traversing the tunnel, you’ll be in free fall, so you won’t experience orthostatic hypotension. Astronauts often experience it when they return to earth, according to NASA, but you probably won’t spend enough time en route for it to be a problem.

It’s easy to answer these questions with the advantage of nine decades of scientific advance, of course, but I think that it would have been easy to answer them even back in 1922. As with the bridgekeeper in Monty Python and the Holy Grail (“He who would cross the Bridge of Death must answer me these questions three”), the first two questions are irrelevant, suggesting that the purpose was not to pose a serious challenge but to attract the attention of the press. Voliva was good at that. But he might have presented a formidable challenge when he was seriously trying to argue for a flat earth, especially to audiences without a clear grasp on the evidence for a spherical earth. In the Morning Tulsa Daily World for April 23, 1922, there’s a report of a talk that Colin A. Scott, a professor of education at Mount Holyoke College, gave to the Kentucky Educational Association. According to Scott, most college students “cannot beat the arguments that Volivia [sic], head of the Zion church, puts forward that the earth is flat.” Are we really doing better today?