Stand on the Congress Avenue Bridge in the evening, and you can watch millions of bats set forth across the Austin, Texas sky, freeing the city of mosquitoes. Walk north, and you’re surrounded by live music. Keep going until you reach the state capitol building, carved from native granite. Ponder the memorial to the Texans who died for the Confederacy. Cowboy hats, boots, and skinny jeans aren’t just for hipsters in this part of Austin. Pass the Chancery of the Diocese of Austin, and the statue of St. Francis commanding “Audite Verbum Dei”—“hear the word of God.” Half a block later, you’ve reached the headquarters of the Texas Education Agency (TEA).

Last Tuesday, at high noon, a few hundred Texans joined an overheated T. rex on the TEA’s front steps to rally in support of science education. These folks could tell you that Austin’s bats are Mexican free-tailed (Tadarida brasiliensis), and that the Capitol’s walls are carved from Town Mountain granite dating back over a billion years. They came to tell the state board of education that Texas students need accurate textbooks, and to urge the board not to let creationists rewrite the books publishers were ready to sell Texas schools. Friend of Darwin recipients Ron Wetherington and Zack Kopplin were there, as were cell biologist Arturo DeLozanne and emcee Kathy Miller, from our friends the Texas Freedom Network.

Last Tuesday, at high noon, a few hundred Texans joined an overheated T. rex on the TEA’s front steps to rally in support of science education. These folks could tell you that Austin’s bats are Mexican free-tailed (Tadarida brasiliensis), and that the Capitol’s walls are carved from Town Mountain granite dating back over a billion years. They came to tell the state board of education that Texas students need accurate textbooks, and to urge the board not to let creationists rewrite the books publishers were ready to sell Texas schools. Friend of Darwin recipients Ron Wetherington and Zack Kopplin were there, as were cell biologist Arturo DeLozanne and emcee Kathy Miller, from our friends the Texas Freedom Network.

Inside the building an hour later, the board gathered to hear public testimony. Former board chairman Don McLeroy was among the first speakers. He followed creationists Royal Smith and Ide Trotter, both of whom have been part of the state’s landscape nearly as long as the Capitol’s sunset red granite. Trotter declared that the textbooks under consideration failed to live up to the board’s 2009 insistence on presenting “all sides of the scientific evidence” on evolution. Moments later, McLeroy proclaimed his endorsement of the books on the grounds that they provide too little evidence for evolution to convince students. “Even the units on evolution support what the Bible says, because, as demonstrated, they don’t even support evolution,” he insisted. Eric Meikle did a nice job dissecting McLeroy’s claim.

After the initial bout of creationist speakers, the textbook’s defenders held sway. A mother brought her daughter, who was missing a day of sixth grade, to ask that the books not be watered down. A ninth-grader perched on one leg as he spoke on his own behalf about the need for great new textbooks that would teach him about evolution. Texas Citizens for Science president Steve Schafersman denounced the flawed review system that let creationists pressure publishers. Scientists and ministers spoke in turn, echoing the message that evolution belongs in textbooks, and creationism doesn’t. I lost count over the four hours of testimony, but it felt like there were three or four speakers in support of evolution and climate change education for every creationist or climate change denier who spoke.

After the initial bout of creationist speakers, the textbook’s defenders held sway. A mother brought her daughter, who was missing a day of sixth grade, to ask that the books not be watered down. A ninth-grader perched on one leg as he spoke on his own behalf about the need for great new textbooks that would teach him about evolution. Texas Citizens for Science president Steve Schafersman denounced the flawed review system that let creationists pressure publishers. Scientists and ministers spoke in turn, echoing the message that evolution belongs in textbooks, and creationism doesn’t. I lost count over the four hours of testimony, but it felt like there were three or four speakers in support of evolution and climate change education for every creationist or climate change denier who spoke.

As tends to happen at these hearings, the creationist board members saved their questions for those who they knew agreed with them, or those they thought could be tripped up. Don McLeroy, a private citizen since the 2010 elections, was allowed to run long, and enjoyed plenty of follow-up questions, while evolutionary biologists, ministers, and teachers were all held to a two-minute statement, and were rarely asked any questions to let them share their experience and expertise further.

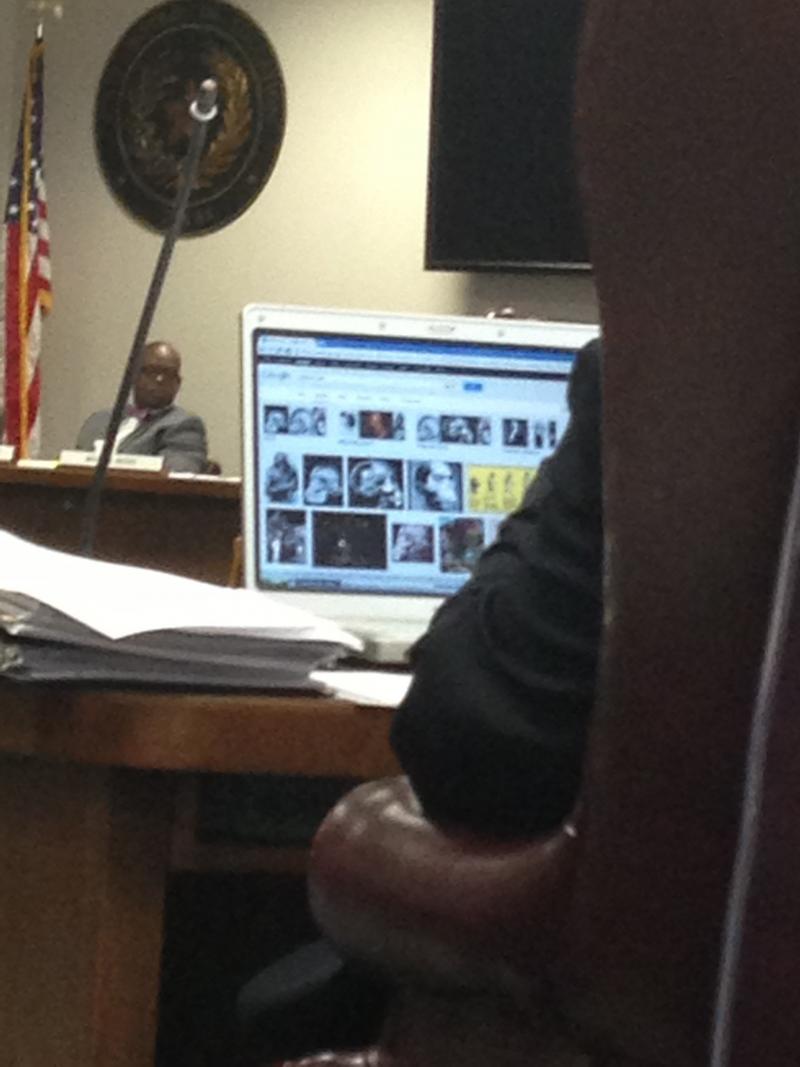

By the halfway mark, board members David Bradley and Ken Mercer—the board’s creationist ringleaders—were feeling punchy. Each dared testifiers to show one place where a book mentioned creationism or any god. Mercer stopped Googling images of the Piltdown Man long enough to offer a bounty: “If you find Jesus, Buddha, Muhammad anywhere in the science TEKS, I’ll give you $500.” Bradley offered to double the bounty, and then offered a bounty for anyone who could point to the phrase “separation of church and state” in the Constitution.

By the halfway mark, board members David Bradley and Ken Mercer—the board’s creationist ringleaders—were feeling punchy. Each dared testifiers to show one place where a book mentioned creationism or any god. Mercer stopped Googling images of the Piltdown Man long enough to offer a bounty: “If you find Jesus, Buddha, Muhammad anywhere in the science TEKS, I’ll give you $500.” Bradley offered to double the bounty, and then offered a bounty for anyone who could point to the phrase “separation of church and state” in the Constitution.

Due to disturbances in past years when audience applause or sign-waving signs disrupting the board’s deliberations in past years, there was a strict rule against applause, boos, catcalls, signs, or other demonstrations. It was a special thrill, then, to hear even a smattering of applause after I told the board, “To ensure that ‘Texas edition’ is a mark of quality, not a warning label, I ask that you assure publishers they won’t have to make revisions to satisfy these flawed reviews.”

After the last speaker sat, we all had a chance to mingle. Don McLeroy came to thank NCSE for giving him the first-ever Up-Chucky Award, back in 2010. Reporters jockeyed to speak with board members (though TV cameras were gone minutes after McLeroy’s presentation ended), while we activists looked for an opening to share our take on the day’s events. At one point, several creationists surrounded the New York Times education reporter, while Steve Schafersman tried to explain where they were wrong. Creationist board members tested out textbook changes (like epigenetics, as Genie Scott pointed out) that might be able to draw support from a majority of board members.

In the end, most of the board seemed to get the message that Texans want textbooks that present evolution the way scientists understand it—as the only viable scientific explanation for life’s diversity. They also understood that Texans worry about a process that lets creationists rewrite the work of legitimate scientists, and a process that will keep publishers’ revisions secret until the board’s final vote. We still have a lot of work to do before the meeting and final vote in November, but this week’s hearing put us in a strong position as we enter that final stretch.