It’s hard to imagine that tree twigs could change someone’s life, but this week’s Thank a Teacher started with just that. And not just twigs, but leafless winter twigs that might seem to shed little light on a tree’s identity. Such were the tools that one teacher used to intrigue a small group of students who would grow up to change the world.

It’s hard to imagine that tree twigs could change someone’s life, but this week’s Thank a Teacher started with just that. And not just twigs, but leafless winter twigs that might seem to shed little light on a tree’s identity. Such were the tools that one teacher used to intrigue a small group of students who would grow up to change the world.

Some people don’t catch fire for science in high school. Some of them don’t even really get the bug in college, at least in the sense of having that “a-ha!” moment when they develop not just a fondness, but a passion for the topic. My next few stories on the blog will be about teachers who made a difference in college and beyond.

Let’s start with F. Stuart Chapin III – he goes by “Terry” – emeritus professor of Ecology at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks. Since coming to Fairbanks in 1973, Terry has carried out groundbreaking research in ecology, focusing on how plants adapt to low temperatures and changing environments. He has also authored a highly regarded textbook on Terrestrial Ecology, mentored dozens, and taught hundreds. His outstanding scientific research resulted in his being the first Alaskan elected to the National Academy of Sciences. In the last decade, Chapin has expanded his ecology research to include human-environment interactions and has been involved in many national and international efforts, including a major National Research Council (NRC) study called “America’s Climate Choices,” focusing on how societies can adapt to a changing climate.

Let’s start with F. Stuart Chapin III – he goes by “Terry” – emeritus professor of Ecology at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks. Since coming to Fairbanks in 1973, Terry has carried out groundbreaking research in ecology, focusing on how plants adapt to low temperatures and changing environments. He has also authored a highly regarded textbook on Terrestrial Ecology, mentored dozens, and taught hundreds. His outstanding scientific research resulted in his being the first Alaskan elected to the National Academy of Sciences. In the last decade, Chapin has expanded his ecology research to include human-environment interactions and has been involved in many national and international efforts, including a major National Research Council (NRC) study called “America’s Climate Choices,” focusing on how societies can adapt to a changing climate.

I recently wrote Terry to ask whether a teacher had influenced his decision to become a scientist, and his willingness to devote his time to working with others to ensure that scientific knowledge contributes to the public good. It turns out that a teacher did indeed have an outsized impact on Terry’s career choice, but he didn’t come across him until his freshman year in college.

After two years of high school in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, and two at the Deerfield Academy in Massachusetts, Terry went off to college at Swarthmore with no idea what he might want to do. His assigned advisor happened to be an economics professor, so he signed up to major in economics. However—in a lucky break for science—his advisor, upon learning that Terry liked the outdoors, suggested that he try Intro Bio. And the rest is history.

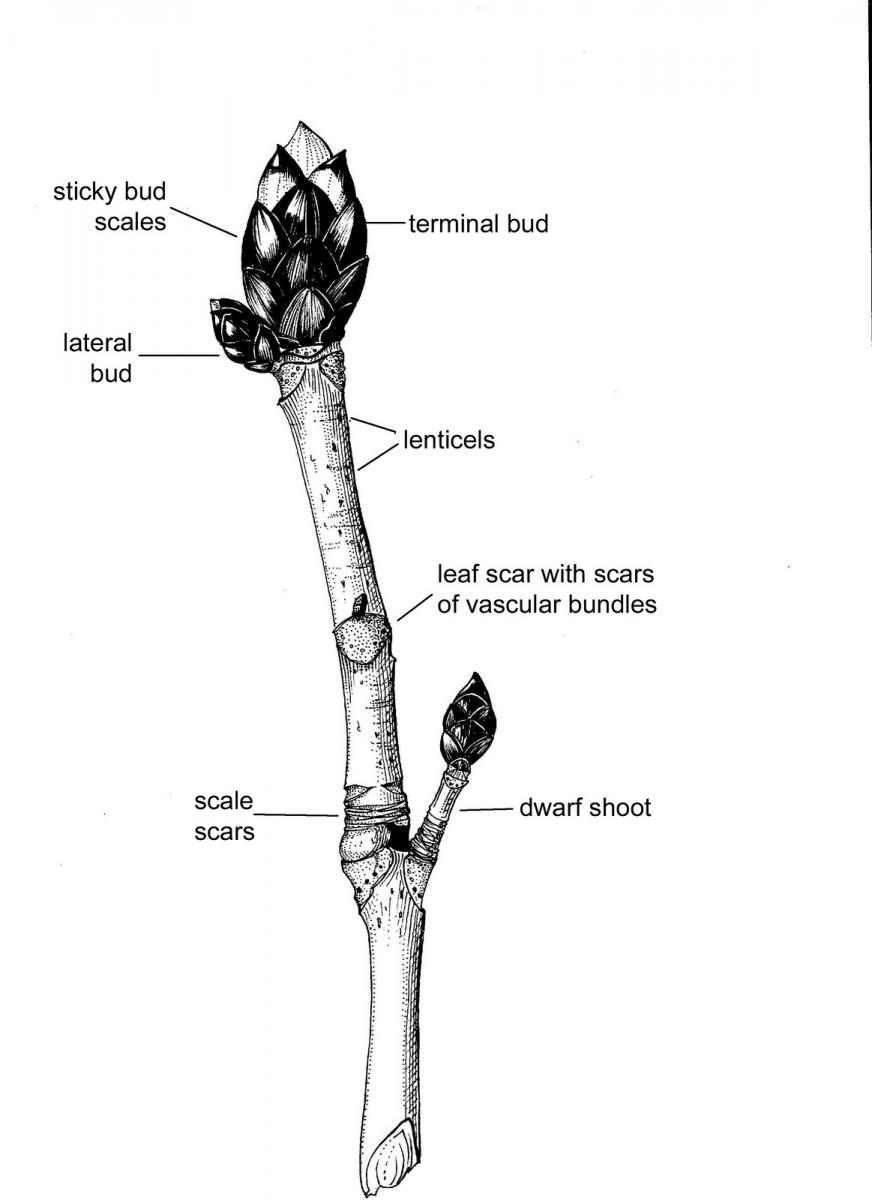

The introductory biology course at Swarthmore was (and is) taught by the entire biology faculty, “each professor taught the unit on their specialty” Terry told me, “so they were passionate about what they taught.” It was the ecology professor, Bill Denison, whose passion captured Terry’s attention. Denison led lots of outdoor field studies and Terry remembers becoming fascinated with a project involving identifying trees by their winter twigs. “Figuring out which trees were there got us into the classical ecological questions like why certain trees are in some places and not others” and a lifelong passion for unraveling ecosystem interactions was born.

The introductory biology course at Swarthmore was (and is) taught by the entire biology faculty, “each professor taught the unit on their specialty” Terry told me, “so they were passionate about what they taught.” It was the ecology professor, Bill Denison, whose passion captured Terry’s attention. Denison led lots of outdoor field studies and Terry remembers becoming fascinated with a project involving identifying trees by their winter twigs. “Figuring out which trees were there got us into the classical ecological questions like why certain trees are in some places and not others” and a lifelong passion for unraveling ecosystem interactions was born.

Terry was not the only student captivated by science under Denison’s tutelage. A group of Terry’s fellow freshman continued studying ecology together throughout their four years at Swarthmore, and each of them went on to earn graduate degrees in the subject.

Denison was also deeply concerned about social issues and that passion rubbed off on his students. As Terry told me, “The fact is that this teacher became a mentor not only with respect to biology but how we were developing as individuals and as professionals. Denison didn’t separate biology from life.”

An influence like that can play out years and years later. When Terry’s ecological studies revealed how quickly Alaskan habitats were changing, it was natural for him to consider the consequences for people. “Those of us who continued in ecology had a strong bent for addressing social issues,” Terry says. “That’s why I got interested in climate change, and how ecological changes have affected Alaska’s native peoples.”

The year after Terry graduated from Swarthmore, Dr. Denison moved to Oregon State, where he continued to transform students’ lives. Terry and his fellow Swarthmore classmates stayed in touch with him until his death in 2005. In Oregon, Denison was one of the pioneers opening up a new habitat to ecological research—the forest canopy. An article, “Treetops Yield their Secrets” published in 1994 in the New York Times Science section describes the “derring-do” that was required to study this previously unseen world. I wonder how many students who came to climb trees stayed to become scientists?

Have a story about a teacher who brought science to life? Tell me about it—reid@ncse.com.