In part 1 of “The Two Woodrows,” I began with Woodrow Wilson’s comment, “of course, like every other man of intelligence and education, I do believe in organic evolution. It surprises me that at this late date such questions should be raised.” Wilson wasn’t himself particularly interested in organic evolution—the references to evolution and to Darwin in his writings, as far as I can tell, are mainly in the service of his analogy of political life to organic life, a guiding principle of his political thinking owing largely to the influence of the eighteenth-century statesman and political theorist Edmund Burke. Wilson’s acceptance of organic evolution, I suggested, was probably due to the influence of his uncle James Woodrow, a Presbyterian theologian who found himself in trouble with the board of directors of Columbia Theological Seminary in 1883 over his suspected acceptance of evolution.

In part 1 of “The Two Woodrows,” I began with Woodrow Wilson’s comment, “of course, like every other man of intelligence and education, I do believe in organic evolution. It surprises me that at this late date such questions should be raised.” Wilson wasn’t himself particularly interested in organic evolution—the references to evolution and to Darwin in his writings, as far as I can tell, are mainly in the service of his analogy of political life to organic life, a guiding principle of his political thinking owing largely to the influence of the eighteenth-century statesman and political theorist Edmund Burke. Wilson’s acceptance of organic evolution, I suggested, was probably due to the influence of his uncle James Woodrow, a Presbyterian theologian who found himself in trouble with the board of directors of Columbia Theological Seminary in 1883 over his suspected acceptance of evolution.

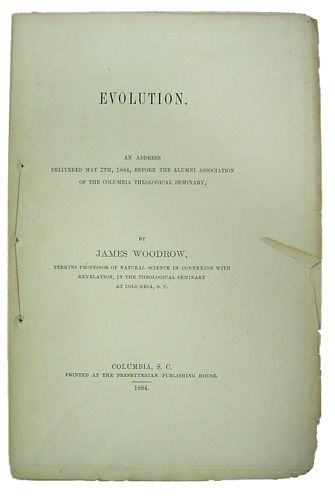

Complying with a request from the board to clarify his views, Woodrow gave a lecture on evolution in 1884, published in the same year. After addressing principles of biblical interpretation in general, he turns to evolution in particular. He emphasizes that, properly defined, evolution “does not include any reference to the power by which the origination is effected,” thus making space for the idea that God works through evolution. Such a definition “necessarily excludes the possibility of the questions whether the doctrine is theistic or atheistic, whether it is religious or irreligious.” Moreover, evolution is irrelevant to the great truths of religion: “[H]ow can either our acceptance or rejection of Evolution affect our love to God, or our recognition of our obligation to obey and serve him?” That might establish the compatibility of evolution and a generic theism, but will it suffice to establish the compatibility of evolution with Christianity in particular?

Acknowledging that the question remains whether evolution contradicts the teaching of the Bible, Woodrow suggests that the point of the Bible’s teachings about God’s relation to the creation is to show that “he is equally the Creator and Preserver, however it may have pleased him, through his creating and preserving power, to have brought the universe into its present state.” Reviewing various interpretations of Genesis, he argues that it is debatable which is correct. “It is said that God created; but, so far as I can see, it is not said how he created” (emphasis in original). Since there are, he holds, possible interpretations that are compatible with evolution, “we are not at liberty to say that the Scriptures are contradicted by Evolution.” The soul, however, he holds to be immediately created, as the Bible teaches, but, he hastens to add, “I have not found in science any reason to believe otherwise.”

If these theological and hermeneutical considerations aren’t to your taste, you’ll like the next section of the lecture. Honestly, if he had used the acronym FAQ, you might have mistaken it for early drafts of pages from the TalkOrigins Archive. He defends a version of the nebular hypothesis of the origin of the solar system before turning to descent with modification. As evidence for it, he cites the fossil record, homologies, rudimentary (or vestigial) organs, embryology, and biogeography. “[I]n view of all these facts the doctrine of descent with modification, which so perfectly accords with them all, cannot be lightly and contemptuously dismissed.” And he piously adds, “the more fully I become acquainted with the facts of which I have given a faint outline, the more I am inclined to believe that it pleased God, the Almighty Creator, to create...in accordance with the general plan involved in the hypothesis I have been illustrating.”

How did the board of directors of Columbia Theological Seminary take it? A resolution condemning the belief that Adam’s body was the product of evolution and enjoining Woodrow not to teach it was introduced, but it failed to pass. Instead, a resolution expressing sympathy and agreement for Woodrow’s acceptance of “the infallible truth and absolute inerrancy” of the Bible was passed. But he wasn’t out of the woods yet. The South Carolina synod of the Southern Presbyterian Church reviewed the case. Clement Eaton, writing in the Journal of Southern History (1962), described Woodrow as defending himself ably before the synod. (Eaton also observed that he there “made a startling distinction between the creation of Adam’s body and of Eve’s body”—Adam’s anatomy was evolved, or could have been, but Eve’s was directly created by a divine miracle, since the Bible clearly insists on it: see Genesis 2:22.)

His able defense notwithstanding, Woodrow lost. The South Carolina synod passed a resolution expressing disapproval of the teaching of evolution “except in a purely expository manner, without intention of inculcating its truth.” The synods of Georgia, Alabama, and South Georgia and Florida also expressed their disapproval, and since those four synods together controlled Columbia Theological Seminary, they were thus able to prohibit the teaching of evolution there. The board of directors then asked Woodrow to resign; when he refused, he was dismissed. He then appealed to the four synods. Georgia and Alabama upheld his dismissal, but South Carolina and South Georgia and Florida didn’t. Without a majority among the synods, the board decided that his dismissal was improper—but requested his resignation again. A few years later, the South Carolina synod demanded his resignation; he refused, and the board dismissed him again.

Woodrow then appealed to the General Assembly of the Southern Presbyterian Church, the court of final appeal, again arguing that his acceptance of evolution was not in conflict with either the Bible or the doctrines of the church. To no avail: the Assembly rejected his appeal by a vote of 139 to 31, and (as Eaton writes) “declared the doctrine of the Church to be that Adam’s body was directly fashioned by God out ‘of the dust of the ground without any natural animal parentage of any kind.’” Fortunately for Woodrow, he was able to work at the University of South Carolina, where he taught geology and mineralogy, and where he was president from 1891 until 1897. He continued to be active in the church, even serving as moderator of the South Carolina synod—the same synod ultimately responsible for his dismissal from the seminary—in 1901. He died in 1907, by which time his nephew Woodrow Wilson was the president of Princeton University.