Last Tuesday afternoon, NCSE’s intrepid (but at the time, flu-ridden) communications director forwarded me an urgent request for assistance. Slate science editor Laura Helmuth was moderating a panel at the annual American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco, and one of her panelists had bailed. Could I step in tomorrow, to talk about opinion journalism for scientists and science journalists?

Luckily, AGU is progressive enough to offer on-site childcare at its meeting, so I was able to accept the offer. And despite relatively short notice, I was able to assemble an argument that I’m sufficiently pleased with that I’d like to share it now, with you.

Dan Janzen, 2009, by Sam Beebe (using a CC-BY license)

I opened with a quotation from Dan Janzen’s 1986 essay on “The Future of Tropical Ecology,” a seminal document in the creation of the discipline of conservation biology, a scientific discipline dedicated to shifting policy. Janzen, in the usually staid pages of Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, wrote:

Whether there is a future for tropical ecology, and of what it will consist, does not lie in the unveiling of yet another intricate animal-plant interaction, in the application of technological marvels, or in the discovery of a crop plant that can be grown with high yield on rainforest soils.…

Engineers build bridges, writers weave words, and biologists are the representatives of the natural world. If biologists want a tropics in which to biologize, they are going to have to buy it with care, energy, effort, strategy, tactics, time, and cash. And I cannot overemphasize the urgency as well as the responsibility. …If the tropics of the world go under, biologists of the world will have no one but themselves to blame. We can see very clearly what is happening, what will be the irreversible consequences for biology and humanity, and how the solutions must be constructed.

I think the same argument could be made about the state of climate science today. Scientists have a depth of understanding of the crisis at hand that few others do, and have a responsibility to share that understanding. Too often, scientists will lay out all that we know about the shape of the crisis before us, and then demur when asked what we should do. Sometimes they do so out of fear, either fear of political attacks (as if staying silent about policy protected NCSE board member Ben Santer or NCSE Friend of the Earth award-winner Michael Mann when their science proved politically inconvenient). Other times, the fear is that speaking about policy, or expressing a personal opinion, will make the scientist seem less credible.

I think that’s misguided for two reasons. First, refusing to answer when asked what we should do sounds like a cop out. If a scientist lays out evidence that there’s a crisis, but then shrugs when asked about solutions, it doesn’t make the audience feel like there’s much of a crisis. And it’s not credible: of course scientists have opinions, and there’s no reason to pretend otherwise.

Second, the public respects scientists and wants to know what scientists think. The biennial Science and Engineering Indicators report from the National Science Board consistently finds that scientists are highly-respected, with only the military enjoying more public confidence. A survey by the Pew Center found the same, with scientists basically tied with teachers, and only slightly lagging the military in terms of which groups contribute a lot to society’s well-being.

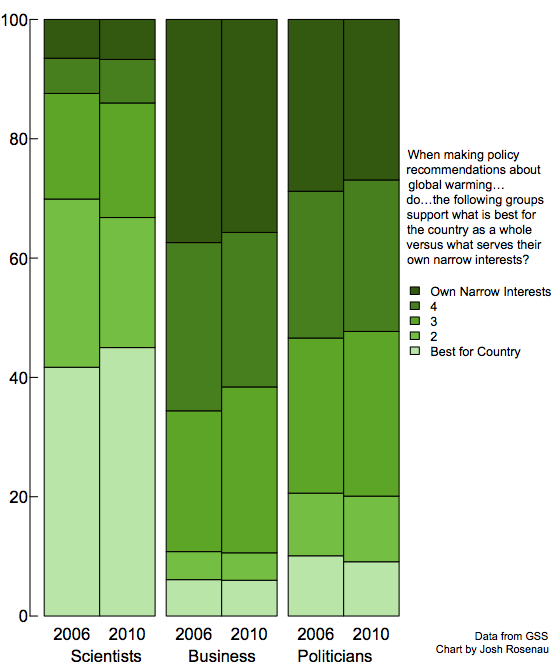

Scientists have the public’s trust by other measures. In 2006 and 2010, when the General Social survey asked (on the National Science Board’s behalf) whether scientists’ recommendations about global warming policy are generally motivated by their own narrow interests or by the greater needs of the nation, people overwhelmingly viewed scientists as impartial, in strong contrast to the perception business leaders and even the politicians elected to represent the nation’s interests. The public trusts scientists, respects scientists, and wants to hear what scientists have to say.

Scientists have the public’s trust by other measures. In 2006 and 2010, when the General Social survey asked (on the National Science Board’s behalf) whether scientists’ recommendations about global warming policy are generally motivated by their own narrow interests or by the greater needs of the nation, people overwhelmingly viewed scientists as impartial, in strong contrast to the perception business leaders and even the politicians elected to represent the nation’s interests. The public trusts scientists, respects scientists, and wants to hear what scientists have to say.

The problem for scientists is that, while they are regarded as highly competent in their field, they are not seen as particularly warm or pleasant. Research by Susan Fiske and Cyndey DuPree shows that the public’s attitude toward scientists is at best technocratic (similar to accountants, for instance) and at worst, in a cluster with lawyers and CEOs, groups known for high rates of psychopathy.

Part of the problem is simply that too few people know a scientist. A 2013 survey by Research!America found that 70% of Americans, asked to name a living scientist, couldn’t. Of those who said they could, most (43%) named Stephen Hawking, with racist, misogynist James Watson and pseudoscientific crank Dr. Mehmet Oz also making the list of common responses. The slide I showed was from 2009, when 5 of the 8 top “living scientists” named were not actually living (Sagan, Salk, Curie, Einstein, Pasteur). Other such surveys often yield names like Al Gore, Bill Gates, or others who, while at least living, are not scientists. If people only know scientists in the abstract, how can they feel a warmth or personal connection to them?

Creating such personal connections matters. As researchers recently demonstrated, even a 20 minute conversation with a stranger from a stigmatized group produced lasting changes in the attitude not only of the person who answered the door, but in the entire family’s outlook on, in that experiment, marriage equality and gay rights. Making a personal connection—letting the audience see the canvasser not just as a stereotype but as a living, breathing human being, and creating a relationship of mutual respect—made a dramatic and lasting difference. As one of the researchers told the New York Times, “Instead of robotically delivering the message, we coached canvassers to be respectful, to listen, to ask questions and dig deeper, and not to judge voters.” For scientists interested in overcoming a perception of being distant and cold, that’s good advice.

Making science personal has other potential benefits. Perhaps counterintuitively, highlighting how science is tentative and deeply human can help cut through people’s resistance and make the science more relatable. Emphasizing that scientists can and do screw up in the lab gives a chance to explore how we correct those errors. Talking about how scientific conclusions are tentative gives a great opportunity to show how some results are actively debated (how high will oceans rise in the next century? which dinosaurs had feathers?), and why scientists are so confident in others (climate change is happening, all life can be traced to a common ancestor). Tracing how scientists move from their acknowledged expertise on the science to form opinions on policy works the same way, by exploring the values and influences that shape those opinions, and how the science informs those opinions. Janzen’s essay is a great example of that dynamic at play.

That human connection is you go from talking about baseball statistics and create a best-selling book about a David and Goliath battle and then an Oscar™-nominated movie starring Brad Pitt, and how Rebecca Skloot turned the story of cells in a laboratory into a best-seller (optioned by Oprah Winfrey for movie production) about a family’s intergenerational struggles and her own detective work to trace the history of Henrietta Lacks and the ubiquitous HeLa cell line derived from her cancerous tumor.

Sadly, being personal in that way is something that we train scientists away from. Scientists are trained not to use the first person singular: they either say “we titrated the solution to…” or worse, phrase it passively, as in, “the solution was titrated to…,” and scientific writing is famously unemotional. That lack of personality is important in reporting science to other scientists, but it’s deadly in presenting to the public. Too often, science is simply presented as a collection of statements about the world, making it easy for science deniers to trot out their own statements in opposition. Scientists can cut through that by explaining where their statements come from, the process of science. The power of science doesn’t come so much from its collection of facts, but from the process scientists use to vet and examine those facts, and that process is all about people being people. It’s a story we should be proud to tell, and to use to share and justify our opinions.