Update: The survey described below reflects the input from a group of self-selected educators, not a randomized sample. A more robust national survey to determine whether, where, and how climate and global change topics are being taught is much needed, but until such a survey is deployed, the "user needs" survey described below provides a snapshot of the interests and practices of many science educators today in the United States.

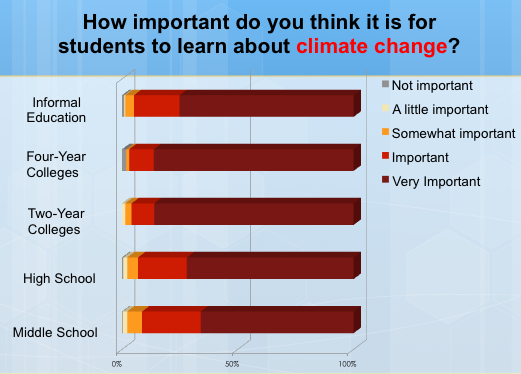

Teaching climate change is considered a major priority for science educators, especially in higher education, where 97% indicated in a recent survey that teaching climate change was "important" or "very important". The survey also found that 90% of the educators responding to the web-based survey have received professional development around climate change or atmospheric science, but have had less support around related topics, such as ocean acidification.

Last week in Denver at the annual Geological Society of America conference, I had the privilege of presenting some of the findings from the survey we conducted with over 1,300 science educators. The aim was to learn whether, where, and how they teach about climate and other global change-related topics, such as biodiversity loss and freshwater pollution.

The survey, a collaboration between NCSE, BSCS, and the University of California Museum of Paleontology, asked fifty questions of educators from middle school all the way up to four-year colleges (and informal educators too!) from across the country. The data is helping us in developing a new website that will be released in 2015 called Understanding Global Change, complementing the popular Understanding Evolution and Understanding Science websites.

Here are a few of the highlights that stand out from our initial slice of the data:

- Strong majorities—more than two-thirds of middle and high school teachers and 87% of four year college educators—agreed or strongly agreed that students were interested in learning about solutions and responses to human impacts.

- 75% (informal) to 92% (two-year colleges) use the Internet to access teaching resources at least once a week; half of all teachers surveyed use it everyday.

- Nearly all (98%) have had professional development on climate or the atmosphere, while fewer than half have had it on freshwater issues and only about a third on urban environmental topics.

- About 90% found that professional development improved their confidence in teaching; professional development also seemed to correlate with whether a global change topic was taught or not, although that may be conjecture at this point.

- Fewer than 10% reported being encouraged not to teach about climate change. When this did occur, it came from parents or administrators, less often from community members, other teachers, or students.

- Two thirds (middle and high school) to three quarters (four year colleges and informal educators) felt that their students were interested in local environmental impacts.

In many respects, the above information is reassuring. We’re making some progress, although we should note the respondents were self-selected and largely very experienced teachers. A more robust survey is needed to drill down into these issues.

It is also worth noting that there was not 100% agreement among all the respondents, especially about climate change. One survey responder wrote:

After looking at the evidence myself, scientists have not shown a convincing link between human behavior and climate change. The earth has been undergoing climate change for millions of years. A 1.5 degree increase over the last 150 years is nothing to freak out about. 60 million years ago the earth's oceans were almost 20 degrees warmer than they are now.

Could human activities heat the ocean and atmosphere beyond the most severe IPCC scenarios? Some scientists think that they could. Meanwhile, the task at hand is doing everything we can to help people understand the implications if not the essentials of the science.

Clearly, there's still work to be done to provide teachers with the background and tools they need to effectively teach about the processes and rates of global change—an essential part of the Next Generation Science Standards.

Meanwhile, we’ll be digging more deeply into the survey data to help inform the development of the Understanding Global Change website. We'll also help the broad climate literacy community fine-tune strategies to provide learners with the knowledge and knowhow they need to tackle our climate and energy challenges.