Which is more amusing: the fact that a geocentrist was actually considered to testify for the defense in the McLean v. Arkansas trial, or the fact that a flat-earther wanted to be considered to testify for the prosecution in the Tennessee v. Scopes trial? True, in the twentieth century, thinking that the Earth is flat is even nuttier than thinking that the Earth is at the center of the solar system, so it’s tempting to give the nod to the flat-earther. But if you look beyond the beliefs to the context, and remember that the Arkansas attorney general’s office took Gerardus D. Bouw seriously enough as a potential expert witness to include him on a list of witnesses submitted to the court (see “In the Orbit of McLean”), while the Scopes trial attracted all sorts of self-publicizing eccentrics not taken seriously by the attorneys involved, then you might be inclined to favor the geocentrist. Well, I’ll tell you about the flat-earther, and you can decide for yourself.

The relevance of flat-earthery to the dispute over teaching evolution was apparent well before the Scopes trial. In 1922, Edwin Grant Conklin, then a professor of zoology at Princeton University, took to the pages of The New York Times to castigate the antievolution crusade recently launched by Billy Sunday and William Jennings Bryan. After sketching the evidence for evolution, Conklin lamented, “If only the theological opponents of evolution could learn anything from past attempts to confute science by the Bible they would be more cautious.” Exhibit A was the shape of the Earth. Despite denunciations of the idea that the Earth is a sphere as opposed to Scripture, Conklin wrote, “Today only Voliva and his followers at Zion City maintain that the earth is flat, and the heavens a solid dome, because this is apparently taught by the Scriptures.” Evidently Voliva was famous enough not to require any introduction then.

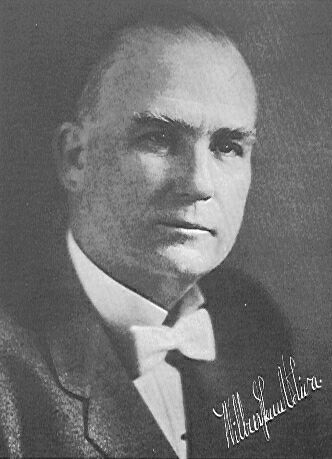

Wilbur Glenn Voliva was born in rural Indiana in 1870. Devoutly religious, he was ordained at the age of nineteen. After studying at a series of Bible colleges, he graduated with a bachelor’s degree from Hiram College and became a pastor in Washington Court House, Ohio. Dissatisfied with his position, he was on the verge of resigning when he was impressed with reports of the work of the evangelist and faith-healer John Alexander Dowie (1847–1907). Eager to become part of Dowie’s work, Voliva was ordained in his Christian Catholic Church, directing its work in Chicago and Cincinnati before emigrating to Australia in 1901 to direct its work there. After Dowie suffered a stroke in 1905, he summoned Voliva from Australia to oversee Zion, Illinois, a theocratic town that Dowie founded in 1900 and in effect personally owned. Arriving in Zion in early 1906, Voliva, with the support of church elders, promptly took over the town and the church.

By 1914, Voliva had consolidated his power in Zion. According to Christine Garwood’s excellent Flat Earth (2007), “Although Dowie had accepted a globular world, Voliva concluded from scriptural study that the earth must be flat and from 1914 he became increasingly focused on destroying what he called the unholy ‘trinity of evils’: evolution, modern astronomy[,] and higher criticism.” In Zion’s schools, students were taught that the Earth was flat—a vast circular plane with the North Pole at its center and a huge impassable wall of ice surrounding its circumference—and globes were banned. Robert J. Schadewald observed that Voliva ordered the church’s hymns to be rewritten: for example, “Let every kindred, every tribe, / On this terrestrial ball, / To him majesty ascribe, / And crown Him the Lord of All” became “Let every kindred, every tribe, / On this terrestrial plane, / To him majesty ascribe, / And praise his Holy Name.”

Voliva’s influence wasn’t limited to Zion, however. In the era of Arctic exploration and trans-Atlantic flights—the Norge sighted the North Pole in 1926; Lindbergh crossed the Atlantic solo in 1927—Voliva was so reliable a source of outrageous pronouncements on geographical matters that he was constantly in the news. It helped, too, that he was alert to the emerging medium of radio: he is credited with being the first evangelist to own a radio station, WCBD, which was so powerful that its signal could be heard in Australia. It’s not surprising, then, to read in the Berkeley Daily Gazette of June 13, 1925, “Just as the fundamentalists of Tennessee are beginning to get a little worried by all the scientific forces arrayed against them, hope dawns in the person of Wilbur Glenn Voliva, overseer of Zion City, Ill. He is galloping south to Dayton to lend his aid in the prosecution of the high school teacher indicted for teaching evolution.”

Voliva was in fact a little disappointed in Bryan, telling the Chattanooga News, “He doesn’t go far enough in his fundamentalist belief…If Bryan repudiates modern theories of biology, he ought to repudiate modern theories of geology and astronomy as we do.” But he probably would have been willing to testify had Bryan asked him to do so. Indeed, Garwood writes that “he reportedly proposed to Bryan that they run for the presidency of the United States [presumably the ticket would be Bryan for president, a position that he sought three times before, and Voliva for vice president] on a joint platform to eliminate the twin heresies of evolution and a spherical earth.” Alas, Bryan died five days after the Scopes trial ended. As for Voliva, his fortunes, both literal and metaphorical, declined with the Great Depression. By 1937, he was bankrupt, losing control of the church and of Zion. After moving to Florida, he died of cancer in 1942.