The New York Times published eight essays as part of its “Week of Misconceptions” series in early April. Some of the ideas for the essays came from posts on the Times’s science Facebook page, but others were inspired by “areas of confusion that reporters on The New York Times’ science desk encounter again and again.” Topics ranged from pop-culture astronomy (“In an asteroid belt, spaceships have to dodge a fusillade of oncoming rocks”) to fairly mundane (“Baby teeth don’t matter”). I was pleased to see that two of the topics were squarely in NCSE’s wheelhouse: “Climate change is not real because there is snow in my yard,” and “It’s just a theory.”

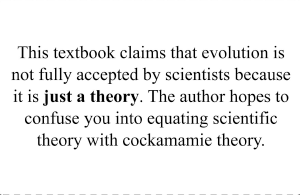

Minda Berbeco and I have both covered the climate change misconception (here and here), but I’ve only briefly talked about the notorious “it’s just a theory” foolishness in my “Hypotheses, Theories, and Laws, Oh My!” post way back in August 2014. This truly is one of the most pernicious and annoying science misconceptions out there, applied to all aspects of science but—of course—mostly and especially to evolution. Browsing through the hundreds of comments on the Times’s science page, I found that it came up again and again—lots of people are frustrated by this one, and I’m excited that the wonderful Carl Zimmer has given me an excuse to talk more about it.

Minda Berbeco and I have both covered the climate change misconception (here and here), but I’ve only briefly talked about the notorious “it’s just a theory” foolishness in my “Hypotheses, Theories, and Laws, Oh My!” post way back in August 2014. This truly is one of the most pernicious and annoying science misconceptions out there, applied to all aspects of science but—of course—mostly and especially to evolution. Browsing through the hundreds of comments on the Times’s science page, I found that it came up again and again—lots of people are frustrated by this one, and I’m excited that the wonderful Carl Zimmer has given me an excuse to talk more about it.

In his discussion of the misconception, Zimmer calls theories “the crown jewels of science,” and the analogy is apt. As anyone in science knows, theories are anything but what’s suggested by the common meaning of “theory”: a hunch or a guess. Ken Miller, quoted in Zimmer’s piece, says, “In science, the word theory isn’t applied lightly … A theory is a system of explanations that ties together a whole bunch of facts. It not only explains those facts, but predicts what you ought to find from other observations and experiments.”

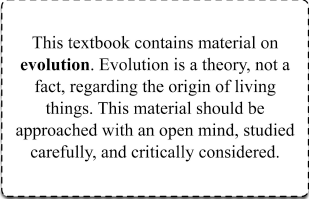

In 2004, Miller spent more than two hours testifying about the meaning of “theory” in Cobb County, Georgia, in a case brought by parents against the school board that had, in 2002, placed warning stickers on all biology books. The plaintiffs won the case and the stickers are no longer spouting their silliness. (Although they won the case, the  decision was vacated on appeal and remanded back to the trial court, where the case was settled without a new trial. Still, no more silliness-spouting stickers in Cobb County.) What did the stickers say? This: “This textbook contains material on evolution. Evolution is a theory, not a fact, regarding the origin of living things. This material should be approached with an open mind, studied carefully, and critically considered.”

decision was vacated on appeal and remanded back to the trial court, where the case was settled without a new trial. Still, no more silliness-spouting stickers in Cobb County.) What did the stickers say? This: “This textbook contains material on evolution. Evolution is a theory, not a fact, regarding the origin of living things. This material should be approached with an open mind, studied carefully, and critically considered.”

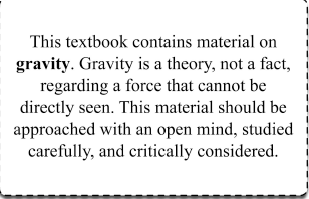

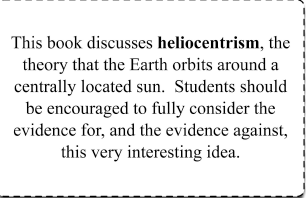

Notice that these stickers don’t target all theories, just evolution. I was working for Pearson on Miller’s high school textbook, in fact, when all of this was happening. I followed the case closely, and compiled a slew of parody cartoons. Particularly  memorable was a page of disclaimer stickers about other theories. “Gravity is a theory, not a fact,” for example. These delightful stickers were designed by Colin Purrington, (formerly a biology professor at Swarthmore College, now a blogger and photographer), who has granted permission to show them here. Aren’t they great? I love them because their complete ridiculousness points out the obvious: nobody feels the need to highlight any theory in science besides evolution as a “theory.” We use up oxygen by saying “the theory of evolution” over and over but rarely bother with “the theory that germs cause illness” or “the theory that the sun is at the center of the solar system.” And this all the bologna about “it’s just a theory” is always in association with evolution. No one ever decries the legitimacy of the periodic table or the structure of the atom. This blatant selectiveness drives me crazy. If you’re going to be wrong about something, at least have the decency to be wrong consistently.

memorable was a page of disclaimer stickers about other theories. “Gravity is a theory, not a fact,” for example. These delightful stickers were designed by Colin Purrington, (formerly a biology professor at Swarthmore College, now a blogger and photographer), who has granted permission to show them here. Aren’t they great? I love them because their complete ridiculousness points out the obvious: nobody feels the need to highlight any theory in science besides evolution as a “theory.” We use up oxygen by saying “the theory of evolution” over and over but rarely bother with “the theory that germs cause illness” or “the theory that the sun is at the center of the solar system.” And this all the bologna about “it’s just a theory” is always in association with evolution. No one ever decries the legitimacy of the periodic table or the structure of the atom. This blatant selectiveness drives me crazy. If you’re going to be wrong about something, at least have the decency to be wrong consistently.

But it would be better not to be wrong in the first place. A better way to think about theories than as guesses or hunches is as maps. That’s the suggestion offered in Zimmer’s essay by the philosopher of science Peter Godfrey-Smith: “To say something is a map is not to say it’s a hunch…It’s an attempt to represent some territory.” Expanding on the suggestion, Zimmer writes, theories are a map: facts are its rivers, hills, and towns. To see how good a map is, we use it to navigate. To test the quality of a theory, we use it to make predictions and test ideas. If you get lost easily following a map, you revise it or dump it (and get a new one). If a theory fails to accommodate new evidence, you modify or abandon the theory (and get a new one).

Through this process of constant testing, modifying, tweaking, testing again, and so  on, we have come to develop some truly foundational theories in science. That is what everyone needs to know. That is what our students must come to understand. I’d love it if teachers included a question on their exams along the lines of: “Explain why this sentence makes no sense: ‘X is just a theory’” (for whatever theory X the exam covers). It would help them to get their students to understand that there are a lot of theories out there and that “theory” in science is not a pejorative term.

on, we have come to develop some truly foundational theories in science. That is what everyone needs to know. That is what our students must come to understand. I’d love it if teachers included a question on their exams along the lines of: “Explain why this sentence makes no sense: ‘X is just a theory’” (for whatever theory X the exam covers). It would help them to get their students to understand that there are a lot of theories out there and that “theory” in science is not a pejorative term.

And when it comes to evolution, by all means talk about it as a theory—but make sure to emphasize what that means. Also, be sure to clarify that evolution is also a fact. As Stephen Jay Gould said: “Evolution is a theory. It is also a fact. And facts and theories are different things, not rungs in a hierarchy of increasing certainty. Facts are the world’s data. Theories are structures of ideas that explain and interpret facts.”

Well saids all around—to Zimmer, Miller, and—of course—Gould. It’s all so obvious, isn’t it? That’s part of what makes this particular misconception so frustrating. But as tempting as it may be to shrug it off when someone says “evolution is just a theory,” it’s imperative that we engage, whether by asking, “what do you mean by ‘just’?” or by directing them to one of Purrington’s stickers.

Well saids all around—to Zimmer, Miller, and—of course—Gould. It’s all so obvious, isn’t it? That’s part of what makes this particular misconception so frustrating. But as tempting as it may be to shrug it off when someone says “evolution is just a theory,” it’s imperative that we engage, whether by asking, “what do you mean by ‘just’?” or by directing them to one of Purrington’s stickers.

Are you a teacher and want to tell us about an amazing free resource? Do you have an idea for a Misconception Monday or other type of post? Have a fossil to share? See some good or bad examples of science communication lately? Drop me an email or shoot me a tweet @keeps3.