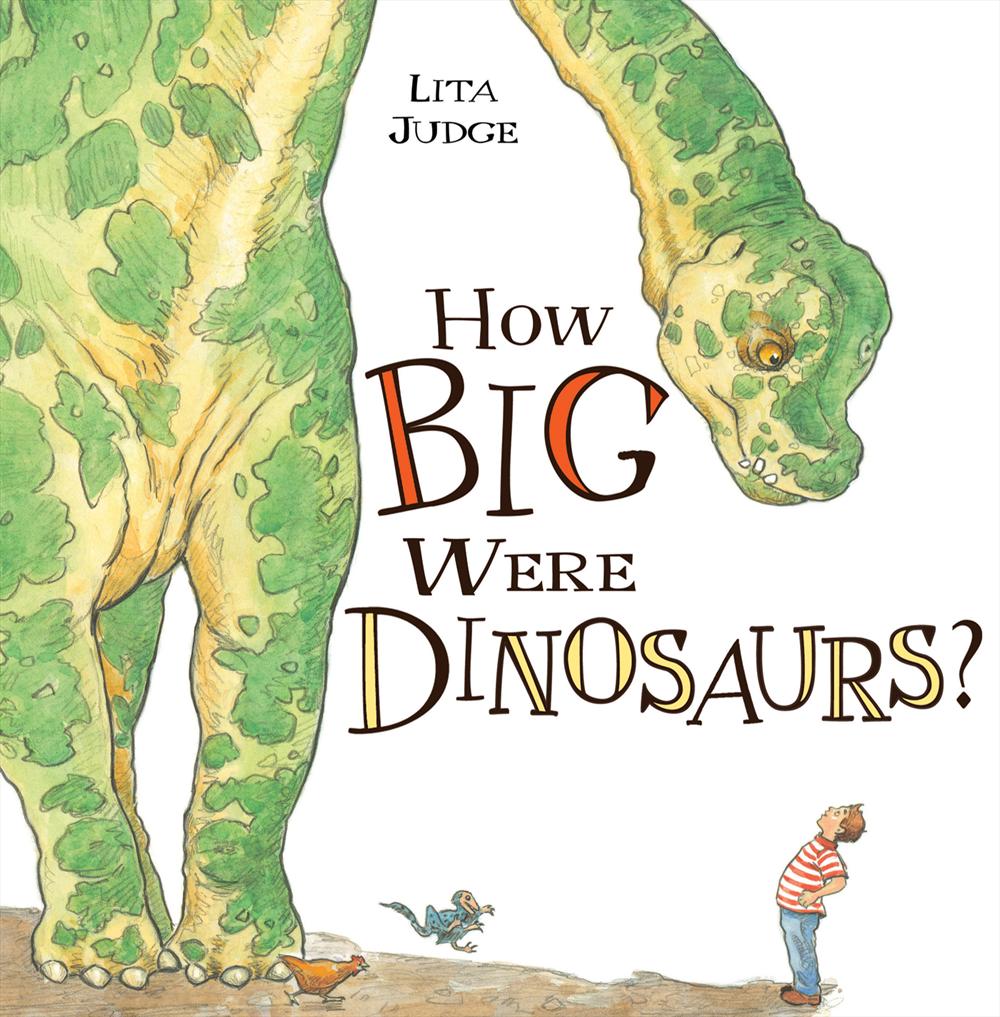

My older daughter’s birthday is right before Christmas, and my younger daughter’s birthday just after. Last year, there was such a glut of gifts that we never even got around to getting some out of their boxes (which was actually quite handy since I was able to re-gift some back to the girls this year in addition to making big donations to local toy drives). Determined not to have a repeat this time around, the majority of the gifts under our tree took the form of the one thing you can’t have enough of: books. Parents out there will understand when I say that these boo ks are also a gift for me, since they offer something new to read come bedtime. The last few nights have been delightful as I’ve gotten to feel the anticipation of reading books I had not yet memorized. Will Peedie find his baseball hat? Will the lonely octopus learn that friends are good to have? If not all princesses dress in pink, what do they wear? You get the idea. It’s also fun because, of course, I can sneak some science onto the bookshelf. One of my picks was How Big Were Dinosaurs? by Lita Judge. And can I tell you? It’s awesome.

ks are also a gift for me, since they offer something new to read come bedtime. The last few nights have been delightful as I’ve gotten to feel the anticipation of reading books I had not yet memorized. Will Peedie find his baseball hat? Will the lonely octopus learn that friends are good to have? If not all princesses dress in pink, what do they wear? You get the idea. It’s also fun because, of course, I can sneak some science onto the bookshelf. One of my picks was How Big Were Dinosaurs? by Lita Judge. And can I tell you? It’s awesome.

Each page in the book introduces a dinosaur and gives kids a modern reference point so they can understand their size: Microraptor could have been stared down by a chicken, Leaellynasaura would have fit in nicely within a waddle* of emperor penguins, Torosaurus had horns as tall as a first grader, Argentinosaurus would have been as long as four school buses and weighed as much as seventeen elephants, and so on.

Now, I could praise the book for its unusual dinosaur picks (not to mention for the fact that they are all actually dinosaurs [not a pteranodon or plesiosaur in sight]), or for the scientifically accurate (lots of feathers!) and funny illustrations, but what brought me out of my post-holiday-sugar-cookie stupor and to my computer was actually the last two pages with the header “How do we know how big dinosaurs were?” There follows four paragraphs, written for children, that show that you do not have to choose between accessibility and accuracy when it comes to writing about science. Is every detail there? Of course not! But nowhere does it read like that’s the intention. Just read this first paragraph:

We can see how big dinosaurs were by looking at fossils of their bones. Sometimes when a dinosaur died, its body was buried quickly by sand or mud. Over millions of years, the mud and sand turned to solid rock. At the same time, water seeped in through the mud carrying minerals that slowly replaced the bone with rock and made a fossil.

She just described permineralization! In a children’s book! How great is that? (But wait! There are other modes of fossilization, you say. True, but does Judge say “this is the one way all fossils are formed”? Nope.) The paragraph goes on,

Scientists uncover fossils in the ground. If they find enough fossils, they can put an entire dinosaur skeleton together. Then they work with artists to draw pictures and make models that show what the dinosaurs might have looked like. If you can see how large a dinosaur skeleton is, you can imagine how this dinosaur compares to animals alive today.

No blowing on loose dust to uncover a perfectly preserved 100% complete skeleton here! It usually takes lots of fossils to get the whole picture! And scientists work with models and artists on reconstructions! Yes we do! The author ends with this: "Microraptor and Argentinosaurus didn’t live at the same time or in the same place, but it is interesting to compare these dinosaurs to get an idea of their range in size."

How great is that? The author goes out of her way to avoid the potential misunderstanding that the dinosaurs in her book all lived at the same time. No one in Jurassic Park ever mentions that Mesozoic Park would have been a better name for an island where both Procompsognathus (Triassic) and Velociraptor (Cretaceous) live, but this children’s book author will help kids come to that conclusion on their own. It didn’t surprise me to learn that Judge wanted to be a paleontologist and went on a field expedition when she was 15. This book demonstrates that even when engaging the youngest learners, you needn’t sacrifice the science.

Well said!

Have an idea for a future Misconception Monday or other post? See some good or bad examples of science communication lately? Drop me an email or shoot me a tweet <at>keeps3.

*I had “flock of penguins,” and Glenn corrected it, leaving this explanation: “At the 4th International Penguin Conference in Chile in September 2000, it was agreed by penguin researchers that they would try to refer to a group of penguins on the land as a ‘waddle’ of penguins and a group in the water as a ‘raft’ of penguins. Or so it is claimed on the internet. Se non è vero, è ben trovato.” I love it when Glenn reviews my posts; I learn a lot.