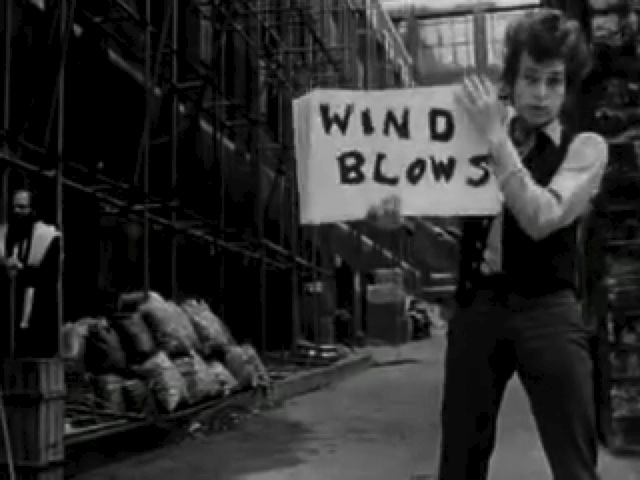

Look out kid

Don’t matter what you did

Walk on your tiptoes

Don’t try “No-Doz”

Better stay away from those

That carry around a fire hose

Keep a clean nose

Watch the plain clothes

You don’t need a weatherman

To know which way the wind blows

-Bob Dylan, “Subterranean Homesick Blues”

I learned about some new research on meteorologists’ views about climate change when Keith Seitter, executive director of the American Meteorological Society, posted a rebuttal to denialist misrepresentations of the research.

The Heartland Institute, a climate change denial group known for mailing pseudoscientific material to teachers, is hardly a credible source, and has a long history of trying to hijack the work of legitimate scholars to advance its agenda. The Union of Concerned Scientists’ Michael Halpern summarizes that history nicely, including the time when the Chinese Academy of Sciences told Heartland to stop misrepresenting its position.

As Seitter reminds us in his blog post, it’s better to go to the source, and he was able to release the paper early, letting us all look over the results.

The researchers surveyed 1854 members of the American Meteorological Society, a scientific society representing a wide range of fields, including weather forecasters (including television weathercasters), oceanographers, and climate scientists. Some are academic researchers, while others serve the public more directly, providing weather predictions and severe weather warnings to mariners, pilots, public health workers, emergency management planners, and the public.

Not surprisingly, the AMS members who work directly on climate (on the long-term patterns, rather than short-term variability) are more likely to accept that climate change is real and caused by humans. About 93% of climate scientists who publish academic research accept that climate change is real and caused by humans. Meteorologists and atmospheric scientists who publish academic research were less accepting, with just under 8 in 10 endorsing the consensus view. The least-accepting group were those who don’t publish, whether they identify themselves as climate scientists or atmospheric scientists/meteorologists (65% and 59%, respectively).

But expertise wasn’t the most important predictor of the survey respondents’ views. Respondents were asked, “To the best of your knowledge, what proportion of climate scientists think that human-caused global warming is happening?” and people who perceived a greater consensus were more likely to agree that climate change is happening and is caused by humans (a finding also true of the general public). Political ideology also played a more important role than expertise, and was only marginally worse as a predictor than perceived consensus. Perceived consensus and personal ideology were equally important in predicting how concerned someone was about climate change. Expertise was the least important predictor for personal concern, and substantially less predictive of acceptance of climate change than either ideology or perceived consensus. Perception of conflict over climate change also reduced acceptance of climate change and concern over its consequences; expertise and perceived conflict were of comparable importance.

What does this tell us? The researchers’ conclusion most important for our purposes:

Fourth, efforts to increase engagement with climate change will have minimal effects if they focus on increasing climate science knowledge alone. Although higher expertise is associated with increased tendency to view climate change as real and harmful, the increase resulting even from major gains in expertise—such as that associated with obtaining a PhD—seems to be quite modest. Increases in knowledge obtained through short-term campaigns are likely to be even smaller. For this reason, engagement campaigns should attempt to deal with other important factors such as consensus and political ideology as well as purely scientific information.

This doesn’t mean that education and expertise are unimportant, of course, but it’s a reminder that education works best when paired with a messenger, and a message, that matches the audience’s cultural context. Conservatives tend toward hostility to climate science, but can be reached by other conservatives, and by figures of authority they trust (including uniformed members of the armed services and business leaders).

Across the board, emphasizing the scientific consensus helps move people to support that consensus. In an educational context, one can easily bridge from “scientists are in general agreement that…” to a discussion of how scientists know what they know. As the researchers emphasize:

The strong relationship between perceived scientific consensus and other views on climate change suggests that communication centered on the high level of scientific consensus may be effective in encouraging engagement by scientific professionals.

Nor is it surprising that Heartland's misrepresentation of the research was aimed at poisoning the well with respect to perception of consensus. Rather than mentioning that 93% of the most expert AMS members agree that climate change is caused by humans (comparable, as John Abraham and Dana Nucitelli observe, to the 97% found in other recent surveys of published climate scientists), the Heartland Institute plucked out the lowest number it could, the finding that only a bit over half of all AMS members agreed that climate change was mostly caused by humans. That figure includes people who don’t study climate science at all and people who have not published in the field. It also ignores the people who say that climate change is real and caused equally by humans and natural processes, or who agree it’s real and caused in part by humans but think there’s insufficient evidence to say how large a role. Explaining why Heartland chose such a misleading number to emphasize, Heartland Institute honcho Joe Bast acknowledged forthrightly, “This is all about ‘spin’”.

In truth, only 5% of AMS members say that climate change is mostly natural, only 7% say they don’t know if it’s happening, and only 4% say it’s not happening at all. Those numbers get even smaller when you get to the most expert group of AMS members, the group whose views shape the expert consensus (rather than reflecting a broader social consensus). While television meteorologists might be the most visible AMS members to much of the public, when it comes to expert opinion on climate change, they don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows.

Image: Still from Don't Look Back (1965), Pennebaker Films. PopspotNYC has a wealth of information on this famous sequence from that tour film.