A young person of my acquaintance, reading Scott Westerfeld’s young-adult novel Peeps (2005)—which has a disturbing amount of scientific information about parasitism in it— drew my attention to the following passage:

“Evolution is mostly about mutations that don’t work, sort of like the music business.” She pointed at her boom box, which was cranking Deathmatch at that very moment. “For every Deathmatch or Kill Fee, there are a hundred useless bands you never heard of that go nowhere. Same with life’s rich pageant. That’s why Darwin called mutations ‘hopeful monsters.’ It’s a crapshoot; most fail in the first generation.”

“The Hopeful Monsters,” I said. “Cool band name.”

I assume that you are already shaking your head no. After all, Lifes Rich Pageant (1986)—no apostrophe—wasn’t a band; rather, it was the fourth studio album (as well as the first gold record) of the band R.E.M. Oh, and the bit about “hopeful monsters” is wrong too.

It is, I hope, a matter of general knowledge that it was Richard B. Goldschmidt (1878–1958) who coined the term “hopeful monster” to

express the idea that mutants producing monstrosities may have played a considerable role in macroevolution. A monstrosity appearing in a single genetic step might permit the occupation of a new environmental niche and thus produce a new type in one step. A Manx cat with a hereditary concrescence of the tail vertebrae, or a comparable mouse or rat mutant, is just a monster. But a mutant of Archaeopteryx producing the same monstrosity was a hopeful monster because the resulting fanlike arrangement of the tail feathers was a great improvement in the mechanics of flying.

I quote from his The Material Basis of Evolution (1940), which is the locus classicus for the concept, but he actually coined it a bit earlier.

In Goldschmidt’s autobiography, In and Out of the Ivory Tower (1960), he dates the term to 1933: “I spoke half jokingly of the hopeful monster in my first publication on the subject, a lecture read by invitation at the World’s Fair in Chicago.” The lecture appeared in print in Science, under the title “Some Aspects of Evolution.” There, summarizing his lecture in a final paragraph, he wrote, “I further emphasized the importance of rare but extremely consequential mutations affecting rates of decisive embryonic processes which might give rise to what one might term hopeful monsters, monsters which would start a new evolutionary line if fitting into some empty environmental niche.”

But—and you knew there was a “but” on its way—at the same time that my young acquaintance was reading Peeps, I was reading, or rather rereading, or rather listening to the audiobook of, Robertson Davies’s Tempest-Tost (1951), a comic novel in which a community theater group in the imaginary town of Salterton, Ontario, is mounting a production of Shakespeare’s The Tempest (1610–1611). Like Ferdinand in the play, I began to seem to hear a faint song in the distance: “Where should this music be? i’ the air or the earth? / It sounds no more: and sure, it waits upon / Some god o’ the island. … But ’tis gone. / No, it begins again.”

My memory was good. There’s a different play called The Tempest, or The Enchanted Island, John Dryden and William Davenant’s 1667 adaptation of The Tempest. (Tempest-Tost refers to it obliquely, when the musician Humphrey Cobbler asks the assistant director Solly Bridgetower, who is approaching him about supervising the music for the Salterton production of The Tempest, “I don’t suppose you’d like to revise your plans and do Shadwell’s version of the play, would you? A much tidier bit of playwrighting, really.” Thomas Shadwell adapted The Tempest, or The Enchanted Island into his 1674 opera of the same name.)

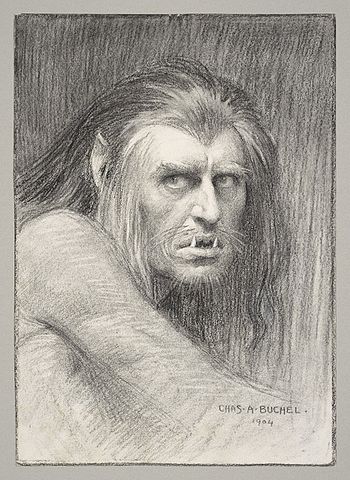

In Dryden and Davenant as in Shakespeare, a group of shipwrecked mariners encounter the savage Caliban, who, longing for a drink from Trinculo’s bottle, kneels in submission. Shakespeare’s Trinculo variously calls Caliban “a very shallow monster,” “a very weak monster,” “[a] most poor credulous monster,” “a most perfidious and drunken monster,” “this puppy-headed monster,” “[a] most scurvy monster,” “[a] howling monster; a drunken monster,” etc.; but Dryden and Davenant’s Trinculo also calls him “a hopeful monster”—hopeful for a tot of wine. There you have it: a hopeful monster sighted in 1667, two hundred and sixty-six years before Goldschmidt’s lecture in 1933.

Am I seriously suggesting that Goldschmidt borrowed “hopeful monster” from Dryden and Davenant? It’s not that he couldn’t have been aware of the play, which was obtainable in 1933—it’s contained in the New Variorum Shakespeare volume of The Tempest (1892), for example. But in none of the versions of The Tempest is Caliban a hopeful monster in the sense of a mutant with prospects. (In fact, he’s the spawn of the witch Sycorax and a devil, according to Prospero, and is generally presented as subhuman.) So despite the phrase occurring in Dryden and Davenant, the difference in meaning militates against the inference that there was any connection.

The phrase is common enough anyhow, occurring, for example, in Aphra Behn’s The Rover, or The Banish’d Cavaliers (1677) (“To fight away a couple of such hopeful Monsters, and two Millions—’owns, was ever Valour so improvident?”) and Joseph Addison’s prologue to Richard Steele’s The Tender Husband, or The Accomplished Fools (1704) (“… the present age; / Breeds very hopeful monsters for the stage”), to cite only the dramatic literature. But I can dream, can’t I? For me, at least, discovering a previously unnoticed source for a famous phrase in the scientific literature is, to coin a phrase, such stuff as dreams are made on.