Eight years ago, the Pew Research Center released a massive survey of American religion. Pew’s researchers surveyed over 35,000 people, a massive sample that was necessary to give representative subsamples of even the smallest of religious denominations. By contrast, most public opinion surveys sample 600-1000 people. This week, they did it again, publishing initial findings from their survey of 35,071 Americans.

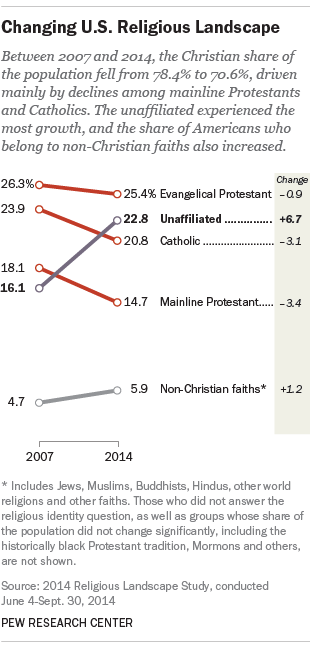

The biggest headline has been a declining membership in conventional religions and the rapid rise in people without a religious affiliation. These include atheists and agnostics, but also people who dropped their religious affiliation but not their beliefs. Most of these Nones believe in a deity or higher spiritual power. They may attend church, pray, or take part in other religious ceremonies. They just don’t see those activities as part of their identity. In this survey, these “Nones” represent the second-largest religious group, after evangelical Protestant Christians.

In the 2007 survey, which I graphed data from last week, Pew’s researchers asked people about their views on evolution, environmental policies, and abortion, but didn’t examine scientific knowledge or attitudes more broadly. If they asked those questions again in the latest survey, the results have not been released yet. But the numbers probably haven’t changed dramatically in the last eight years, so it’s fair to refer to those older results in interpreting the latest findings.

Certainly, the Nones are more accepting of evolution than most other religious groups. Then again, evangelical Protestants are among the least accepting of evolution, yet have done better than most groups at retaining their members. These results alone may be suggestive, but are not enough to test claims about why people might drop their religious affiliations or whether changes in religious attitude may precede changes in attitudes on evolution or other sciences.

That said, there’s reason to think that a religion's approach to science may play an important role in these changes, and that churches which want to retain their membership should pay closer attention to their approach to science. (Not that this is the only issue: the Catholic Church saw the largest decline between 2007 and today, which is probably more attributable to the hierarchy’s failure to confront sexual abuse, to modernize its approach to female leadership, or to adapt to modern society’s approach to homosexuality, birth control, and other issues which force parishioners either to ignore Church doctrine or to feel alienated from it. And this transition surely parallels the broad trend of secularization that we see in other large industrialized nations. Then again, American approaches to religion have always been different from those in Europe.)

To see how religions’ responses to science have shaped the secularization of America, consider the results of a series of interviews and surveys the Barna Group released in 2011. Barna is known for its surveys of evangelicals, but this study looked at Christians more broadly. It explains:

the research uncovered six significant themes why nearly three out of every five young Christians (59%) disconnect either permanently or for an extended period of time from church life after age 15.

Reason #1 – Churches seem overprotective. …

Reason #2 – Teens’ and twentysomethings’ experience of Christianity is shallow. …

Reason #3 – Churches come across as antagonistic to science. …

Reason #4 – Young Christians’ church experiences related to sexuality are often simplistic, judgmental. …

Reason #5 – They wrestle with the exclusive nature of Christianity. …

Reason #6 – The church feels unfriendly to those who doubt. …

Addressing that third item, Barna reports:

One of the reasons young adults feel disconnected from church or from faith is the tension they feel between Christianity and science. The most common of the perceptions in this arena is “Christians are too confident they know all the answers” (35%) [this connects to the 5th and 6th items–JR]. Three out of ten young adults with a Christian background feel that “churches are out of step with the scientific world we live in” (29%). Another one-quarter embrace the perception that “Christianity is anti-science” (25%). And nearly the same proportion (23%) said they have “been turned off by the creation-versus-evolution debate.” Furthermore, the research shows that many science-minded young Christians are struggling to find ways of staying faithful to their beliefs and to their professional calling in science-related industries.

By my reading, 54% of their sample of Christian teens who dropped their affiliation cited anti-science attitudes as part of the reason, with half specifically citing anti-evolution attitudes.

The thing is, most mainline Protestant denominations aren’t anti-evolution, and a growing number of evangelicals are pursuing ways to align their understandings of evolution and their faiths. Tens of thousands of Christian clergy have strongly endorsed the teaching of evolution.

But too often, religious leaders hide their light under a bushel, too fearful of backlash from anti-science parishioners to present their churches’ pro-science views. Pew’s survey shows the consequence: young Christians don’t feel at home in their churches, and drift away.

Now, whether people do or don’t choose to be attached to churches is no deep concern of mine, let alone NCSE’s. If people want to, they should, and all else being equal I’d rather see religious groups speak out in favor of science than against it. In this instance, I think it’s in their interest to do so, too.

American churches have incredibly diverse views on scientific topics, both as a matter of official doctrine and views of the membership. Unfortunately, our national discourse often collapses that diversity down to the most extreme view, usually the anti-science attitudes of the vocal fringe. Creationism (like many of the other issues listed in Barna’s report) is a characteristic of the most theologically conservative churches, the fundamentalist groups that represent a fairly small fraction of Americans. But those groups have come to dominate public discussion of religious attitudes toward science, to the degree that anti-evolution creationism is seen as the default Christian view (not as the fringe position it truly is). As long as the pro-science churches let themselves be defined by the anti-science views of other denominations, it’s little wonder that their ranks are shrinking.