Defining the Problem

Evolution, declares a self-proclaimed "creation-science-evangelist" is "just a pagan religion that has been mixed in with science for nearly a century" (Hovind 1993). A college student responds to a biology lecture on evolution by editorializing in the college newspaper, that "to say that humans evolved from primates is not in accordance with Genesis and is unfriendly to Christian teachings" (Elmendorf 1995). At the same college, another student abruptly leaves a lecture when the human fossil record is discussed.The evangelist, the students, and often the general public, harbor two misconceptions concerning evolution. First, they believe that the theory of evolution was a recent event precipitated by the 1859 publication of The Origin of Species. Second, they see the theory of evolution as solely the work of atheists, and consistent only with a naturalistic philosophy. Young earth creationists exacerbate the situation with their own misinformation; in Men of Science, Men of God, Henry Morris states that in the eighteenth century "geology was beginning to lead people back to the long-age concepts of ancient pagan philosophies" and evolution, "though long out of fashion among scientists, had been advocated by various liberal theologians... and it was beginning to creep back into the scientific literature" (Morris 1982: 51).

While I agree that such rhetoric flourishes in the atmosphere of scientific illiteracy, there is an ignorance of history here as well. The general public knows very little about the theory of evolution beyond the knee-jerk reaction that it makes them uncomfortable. Most are unaware that the theory of evolution has had a long history, and many Christian — often creationist — scientists contributed significantly to the development of the theory of evolution. They are unaware that the entire worldview of unchanging, specially-created species, a creation event lasting six 24-hour days, and a 6000-year old earth had already been abandoned by even religious scientists in the years prior to 1859 — the publication date of Darwin's Origin of Species.

A Possible Solution

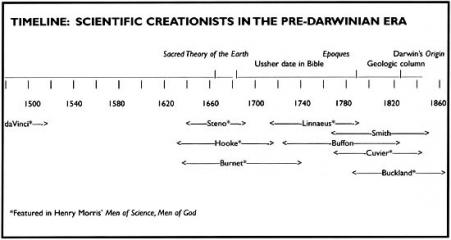

I propose that we can improve the public's perception of evolution by presenting a more complete picture of its development, emphasizing the contributions of Christian — often creationist — scientists from the pre-Darwinian era. I recently presented this information to a general college audience. To assure that the young-earth creationists who attended would agree that I picked "Bible believing scientists", I concentrated on those scientists whom creationist Henry Morris describes as having been a "professing Christian (any denomination) who... believed that the universe, life, and man were directly and specially created by the transcendent God of the Bible" (Morris 1982: 14). To make events and names easier to follow, each person in attendance received a timeline complete with significant dates (Figure 1).

Introduction

Many of the scientists of the 15-1800s adhered to a belief in special creation because there was little evidence to support evolution (Diamond 1985:83). Additionally, because there was no method of determining the age of the earth except from literary sources, and because the Holy Scriptures were thought to be among the most ancient literary sources, biblical chronologies were used as a method of estimating the age of the earth (Haber cited in Glass 1959: 4). The Bishop Ussher date — creation in 4004 BC — was only one of many estimates of the earth's age using biblical chronologies (Dalrymple 1991:14).Difficulties with the Genesis Account

Many hundreds of years before the publication of Darwin's Origin, data that challenged the scientific authority of Genesis began to accumulate in at least four areas that impacted upon the theory of evolution. First, the processes that shape the earth were studied, and scriptural accounts were called into question. Second, exploration of new continents led to the discovery of new animals and plants, many more than were described in ancient texts. Third, it became possible to estimate the age of the earth. Fourth, the geologic column was explored and the fossils were systematically analyzed. New questions arose: Was the earth shaped by catastrophes? Was the Flood of Noah the catastrophe? What were fossils? Was there a relationship between fossils and sedimentary strata? How did modern species originate?Contributions from Scientists Prior to the 18th Century — A Worldwide Flood?

Even today many Christians believe that God once flooded the entire world and that fossils are evidence of life destroyed by this Noachian Flood. Prior to the year 1700, at least four devout Christian men were not convinced by this literal interpretation of Genesis and proposed alternate scientific explanations.Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) observed that the fossil shells in the Alps were frequently found in pairs and rows and stated, "if the shells had been carried by the muddy deluge they would have been mixed up, and not in the regular steps and layers, as we see them now in our time" (quoted in Gohau 1990: 34). Leonardo noted that the Alpine strata showed no evidence of a single violent episode of deposition (Newell 1985: 3&7), and in 1508 rejected the idea of a universal flood (Dean 1985: 95). Though Morris features Leonardo as one of his "men of science, men of God" and discusses his contributions to art, engineering, architecture, anatomy, physics, optics, biology, and aeronautics, Morris makes no reference to Leonardo's theories concernmg fossils or his rejection of the Genesis flood!

Nicolaus Steno (1638-86) described many fundamental geological principles including the process of sedimentation and the law of superposition. Morris asserts that Steno "interpreted the strata — unlike modern evolutionary stratigraphers — in the manner of flood geologists, attributing formation in large measure to the Great Flood" (Morris 1982: 41). In fact, Steno stated that the strata of earth were laid down as sediment from seas or rivers (Geikie 1905: 55). He ruled out the "Great Flood" as a means of depositing fossils although he felt that the Flood was a factor in the folding and disruption of strata (Haber cited in Glass 1959: 22).

Robert Hooke (1635-1703), another of Morris's religious scientists, did not doubt that the Flood of Noah was a real event, but did not believe that it was responsible for the deposition of strata. He thought that the sea would have had to have been in place much longer than the one year implied in Genesis to deposit the thick sedimentary strata seen in England (Geikie 1905:69). Hooke did not consider the Noachian Flood responsible for the placement of fossils either and suggested earthquakes as a possible factor (Haber cited in Glass 1959: 25). A statement from his "Discourse on Earthquakes" portends the concepts of extinction and evolution: "there have been many other species of Creatures in former Ages, of which we can find none at present; and 'tis not unlikely also but that there may be divers new kinds now, which have not been from the beginning" (cited in Faul and Faul 1983:42).

One of the earliest theories of the formation of the earth came from Thomas Burnet (1636-1715) who Morris says, "took the scriptural account of creation and the Flood as providing the basic framework of interpretation for earth history, showing it to be confirmed by known facts of physics and geology" (Morris 1982: 47). In Sacred Theory of the Earth (1681), Burnet depicted the Noachian Flood as the defining event in planetary history (Geikie 1905: 66). However, he realized that the volume of water needed for a universal flood was much greater than that present in the oceans, and his solution was to place much of the water in the atmosphere or under the crust and to dispose of it in underwater caverns (Newell 1985: 37). In Burnet's account, a smooth, sealess, mountainless, paradise world was destroyed as it collapsed into the waters below. The deluge ruined the world, and the earth's axis tilted due to the uneven distribution of debris (Faul and Faul 1983:49). Burnet is important to this historical perspective because he was one of the first scientists whose explanation of the earth's origin and geophysical features abandoned a literal reading of Genesis — a sealess perfect sphere, for example, does not square well with the Genesis creation accounts. His theory was certainly not literal enough for one Bishop Croft, who called Burnet "besotted with his own vain and heathenish Opinions" (cited in Faul and Faul 1983: 50).

At the end of the 17th century the Flood of Noah was considered by many scientists to have been a real event, but was not universally accepted as the defining geological event, and certainly not responsible for depositing fossils. Even the religious scientists of the era proposed theories of the origin of the earth that did not adhere to a literal reading of Genesis.

The 18th Century — A Crowded Ark and an Ancient Earth

The explorations of the American, African, and Australian continents posed severe problems for those who believed that modern species were descendants of those animals rescued from the Flood by Noah. When the kinds of animals were restricted to those found in Europe and the Near East, it was not inconsistent to propose that all of them had fit into the Ark. When the Ark became crowded with koalas, llamas, and bison, scientists of this era were forced further to amend the Genesis account of the origin of species.One of these scientists was Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), the son of a Lutheran minister and one of the founders of modern taxonomy. He is described in creationist literature as "a man of great piety" who "attempted... to equate his 'species' category with the 'kind', believing that variation could occur within the kind, but not from one kind to another kind. Thus he believed in 'fixity of species' (Morris 1982: 49). Other biographers disagree. An investigation of Linnaeus' prolific writings shows that his creation account did not come directly out of Genesis, and his views on the fixity of species changed with time.

Linnaeus proposed that the Garden of Eden was an island near the Equator in the middle of an ocean and that the earth was covered by "the vast ocean with the exception of a single island... on which... all animals could have their being and all plants most excellently thrive" (cited in Hagberg 1953: 198). In time the seas receded and this small Eden became a large mountain with all types of climates . The plants and animals slowly made their way to an appropriate environment first at the time of creation, and again after the Noachian Flood.

Linnaeus believed that fossils were not products of a supernatural flood, but formed naturally in the open ocean. He proposed a unique process to form the sedimentary limestone and shale layers: large mats of sargasso in the ocean prevented wave formation and thus allowed limestone to precipitate. Later on, the sargasso decomposed and was converted to shale, in which fossils were trapped. This was but one of the gradual mechanical processes that Linnaeus thought were responsible for shaping the earth: a "temporis filia, child of time" (quoted in Frangsmyr 1983:143).

Early in his career Linnaeus insisted that each species was a separate creation, stating "We count as many species as there were different forms created" (quoted in Frangsmeyer 1983: 86). Doubts began to arise in 1744 as Linnaeus described a type of toadflax which he called Peloria (malformation). It had been produced from Linaria, but was so extremely different from the parent plant that he assigned it not to just a new species or genus, but to a new class (Frangsmeyer 1983, p 94-5). He was forced to consider the concept of evolution, and by 1751, produced a list of plants, Plantae Hybridae, which were assumed to have two different species as parents, stating, "It is impossible to doubt, that there are new species produced by hybrid generation" (cited in Glass 1959: 149). In Fundamenta Fructificationis (1762) Linnaeus proposed that at creation there were only a small number of species, but that they had the ability to fertilize each other — and did (Frangsmeyer 1983: 97). By 1766 the words "no new species" were removed from the 12th edition of Systemae Naturae. In a comment published posthumously Linnaeus asserted that "Species are the work of time" (cited in Glass 1959: 150). After his death, Linnacus was accused of atheism by the German theologian Zimmerman, to which his son replied "He believed, no doubt, that species animalium et plantarum and that genera were the works of time: but that the ordines naturales were the works of the Creator; if the latter had not existed the former could not have arisen" (citted in Hagberg 1953: 200).

Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (1707-1788), made significant contributions to biology and geology, but perhaps his greatest contributions were a mechanism to determine the age of the earth, and an estimate for the age of the earth that differed significantly from the 6000 years or so calculated from biblical chronologies.

In Epoques de la Nature (1778) Buffon proposed that the earth had cooled from a molten state, and suggested that earth's age might be deduced by determining the time it took to cool to its present temperature. By constructing a series of iron spheres, heating them to a near molten state, then measuring the cooling times and extrapolating these data to a body the size of earth, he deduced that the earth was in excess of 75 000 years old, with an unpublished manuscript proposing a 3 000 000 year age for the earth (Gohau 1990: 94). Buffon's method of escaping the literalism of Genesis 1:11 was to interpret creation "days" as indefinite periods: "The sense of the narrative seems to require that the duration of each 'day' must have been long, so that we may enlarge it to as great an extent as the truths of physics demand" (cited in Geikie 1905: 91).

Lest one suppose that Buffon was increasing the age of the earth to promote evolutionary theories, one has only to look at his contributions in the area of biology to show that this is false. Though by 1753 he considered the possibility of evolution and even saw some supporting evidence, he concluded that "...production of a species by degeneration from another species is an impossibility for nature..." (Lovejoy 1959: 99). Buffon offered three lines of argument against evolution (some of which are still used by young-earth creationists): 1) no new species were known to have occurred within recorded history; 2) hybrid infertility was a barrier to speciation; 3) no "missing links" between groups had been discovered. However, by the 1778 publication of Epoques, Buffon no longer mentioned the simultaneous creation of all species, adopting the notion of gradual appearance instead. (Lovejoy 1959:98-103). Ernst Mayr wrote: "Even though Buffon himself rejected evolutionary explanations, he brought them to the attention of the scientific world" (Mayr 1982: 335).

Buffon's early belief in special creation did not prevent him from getting into trouble with the theology faculty at Sorbonne. In 1751, after studying Histoire Naturelle for two years, the faculty noted the discrepancies between his text and Genesis, and demanded that he retract. Though there is good reason to doubt his sincerity, Buffon replied that he "had no intention to contradict the text of the Scriptures" (cited in Gohau 1990: 93). Twenty-five years later, Buffon found himself in front of the same faculty for his treatment of the age of the earth in Epoques, but he was older, richer, more politically connected, and never did get around to recanting (Faul and Faul 1983: 77).

Before the birth of Charles Darwin, the concepts of a 6000-year-old earth and the special creation of species were being questioned and rejected by scientists who creationists themselves describe as devout Christians.

The 19th Century — Fossils and the Geologic Column

The industrial revolution and the steam engine contributed much to the elucidation of the earth's structure early in the 19th century simply by exposing more of it during mining and the building of canals and roads (Newell 1985: 92). Some contemporary creationists claim that the geologic column was constructed after the publication of Origin to bolster the theory of evolution. In fact, the geologic column was deciphered early in the 19th century, by contributors who were either ignorant of the concept of evolution or opposed to it.William Smith (1769-1839) was a land surveyor and civil engineer who participated in building projects all over England. He constructed a geological map of England in 1799, observing that England was constructed of strata which were never inverted, and that even at great distances "each stratum contained organized fossils peculiar to itself, and might, in cases otherwise doubtful, be recognized and discriminated from others like it, but in a different part of the series, by examination of them" (cited in Geikie 1897: 233). His results, published in 1816 in Strata Identified by Organized Fossils, demonstrated that fossils were not randomly buried, as in a flood, but always occurred in a definite order in the geologic column. Marine species were often found between strata containing terrestrial species — a real blow to flood geology. Smith never formulated a theory of fossil deposition and was, in fact, a literal creationist. "Neither Smith nor [Rev Joseph] Townsend [a publisher of Smith's results] grasped the idea that time was involved in laying down the successive strata, and thought they had contributed support to Mosaic cosmogony" (Haber cited in Glass 1959: 248).

Georges Cuvier (1769-1832), was a French Lutheran anti-evolutionist and founder of comparative anatomy. He is described by Morris as the "chief advocate of multiple catastrophism, believing the Flood to be the last in a series of global catastrophes in earth history" (Morris 1982: 57; italics added). Cuvier was aware of the sequential nature of the fossil record from his own research on the geologic column of the Paris Basin. His paper comparing present day elephants to fossil elephants from Siberia provided evidence that fossils were the remains of extinct animals. Nevertheless, Cuvier was convinced that "species were fixed, immutable and independent" on the basis of scientific observations, not scripture. He examined a number of mummified creatures filched from the graves of Egyptian pharaohs, and found these 3000 year-old specimens to be taxonomically identical to living species (Faul and Faul 1983: 139). To reconcile the obvious changes seen in the fossil record with his belief in fixity of species, Cuvier proposed that the sequential nature of the fossil record was the result of five localized catastrophes. These "revolutions", to use his (time appropriate) word, were caused by the influx of ocean water or transient floods. He further believed that animals were replaced in a flooded area by migration from other areas (Gohau 1990: 131-3). Cuvier never suggested that the floods were global, and it was Jameson's translation into English which suggested that the final catastrophe was the Flood of Noah (Strahler 1987: 190). Out of Cuvier's doctrine of abrupt extinctions and successive "revolutions" his students, especially D'Orbigny, inferred the necessity of up to 27 special creations (Lovejoy cited in Glass 1959: 386).

Cuvier objected to evolution for two reasons. He believed that species were designed for a particular environment, a specific place, until a "revolution" occurred. He also pointed out the lack of transitional forms: "If species have changed by degrees, we should find some traces of these gradual modifications; ...This has not yet happened" (cited in Mayr 1982: 368), and "Fossil man does not exist" (cited in Milner 1990: 105). Both of these statements were accurate during Cuvier's lifetime. The theories proposed by Cuvier and his students were hardly in line with a literal view of Genesis, but instead lent scientific support to both "gap-theory" and "day-age" creationism.

William Buckland (1784-1856) was an Anglican priest and author of the 6th Bridgewater Treatise. He is described by Henry Morris as a "strong creationist" who "did accept the geologic significance of the worldwide Flood" (Morris 1982: 64). Bueldand mounted attacks on earlier evolutionary theorists and was a diluvialist early in his career; his first lecture at Oxford was a defense of the Noachian Flood. His book Relics of the Flood described evidence supporting a universal deluge: fossil bones found in the Andes and Himalayas, river gorges, huge boulders obviously not transported by rivers, and large gravel deposits. Eventually, his own research on the alluvial deposits in caves forced him to reconsider his position on the timing of the Flood. He was disturbed not to have found human remains in caves and so moved the date of the Deluge to before the creation of humans (Hallam 1983: 41-3). By 1840, Buckiand accepted Louis Agassiz' theory of continental glaciation as an explanation of the gravel deposits and "erratic" boulders previously attributed to the Noachian Flood. His proposed 1840 revision of his earlier work was to have had the title Relics of Floods and Glaciers, and all references to the biblical Flood were to have been omitted (Dean 1985: 90). Buckland became one of the early "gap theory" creationists after he gave up flood geology.

Conclusion

Long before Darwin dreamed of publishing Origin, devout Christians made fundamental discoveries concerning the classification of species, the formation and age of the earth, and the geologic column. In 1840 the publication of the book that would rock the belief systems of the Western world was nineteen years away from publication. Nevertheless, Genesis was no longer accepted as a scientific treatise, even by devout Christian scientists. The concept of fixed, specially-created species was laid to rest with the work of Linnaeus. Buffon and others estimated the age of the earth to be greatly in excess of 6000 years. Scientists like Cuvier and Buckland, who opposed the theory of evolution, saw the Genesis Flood as, at most, a regional event. The geologic column was in wide use, not because it supported evolution, but because it was useful in industry. A literal reading of Genesis was, to paraphrase Daniel 5:27, "weighed and found wanting," and like any scientific theory, it was modified to accommodate new evidence.The contributions of these real scientific creationists were pivotal to Darwin as he considered the evidence for evolution. Perhaps if the general public learns more of the history of evolution — that the theory of evolution has Christian underpinnings as well as secular and that it is not tied to a particular philosophy — they will be able to appreciate the science of evolution on a less emotional level.