As the creation-science movement attracted greater attention during the early 1970s, many observers expressed surprise at this most recent outbreak of antievolution sentiment. Following as it did the removal of the three remaining antievolution laws passed in the 1920s, creation-science appeared to be an aberration in the intellectual life of the United States. This movement also appeared to be in conflict with the increasingly urban nature of the country, frequently cited as a major reason for the repeal of the earlier antievolution laws during the late 1960s (Nelkin, 1982, p. 34; Larson, 1985, pp. 104-107; Grabiner and Miller, 1974, p. 836). A closer analysis of legislative actions during this period, however, suggests that demographic change represents only a partial explanation of the fortunes of antievolution activity during the late 1960s and early 1970s.

The state of Tennessee represents a particularly good case study of the legislative fortunes of evolution and the significance of demographic change to these fortunes. Tennessee is the only state in which the legislature was responsible for both passage and repeal of antievolution laws. In 1925, as is well known, Tennessee passed the most famous of all antievolution statutes, the Butler Act, which led to the Scopes trial that summer. After significant debate, both the Senate and House passed this bill with overwhelming votes of twenty-four to six and seventy-one to five, respectively (Bailey, 1950, pp. 482-488). Forty-two years later, the legislature repealed this law, in direct contrast to the laws in Arkansas and Mississippi, which were invalidated by court action. Similarly, Tennessee passed the first creation-science law in 1973, which required "equal time" for the Genesis account of creation in biology classes and textbooks. Although this act was struck down in federal courts two years later, Tennessee's action gave an important boost to proponents of such legislation in other states (Larson, 1985, pp. 93-139).

The rural-to-urban shift which has characterized much of American life in the twentieth century also has been clearly visible in Tennessee, as has its impact on the political life of the state. The state was clearly rural in the 1920s, with nearly 74 percent of the population in communities of less than twenty-five hundred. This situation may explain the attraction of Representative George Washington Butler as a focal point in the evolution debate of the 1920s. Butler represented a constituency in the rural north central section of the state which had a white illiteracy rate of 22 percent in 1920, more than twice the state average and nearly ten times the national average. A member of the Primitive Baptist Church, Butler had no more than four years of formal education (Bailey, 1950, p. 476; Fourteenth Census, 1920; Fifteenth Census, 1930).

The census of 1960 indicated a change in the complexion of Tennessee's population. For the first time, more than half the state's residents lived in census-defined urban areas. Since 1920, the rural population had remained largely unchanged while the urban population had more than tripled. At least in part because of the rural-to-urban shift, Tennesseans had become better educated by the 1960s. Among those persons twenty-five years of age or older, the median number of years spent in school was 8.8. Although nearly two years fewer than the nation's median, this was a significant improvement over the situation in 1920 (Eighteenth Census, 1960, part 1, p. 207; part 44, pp. 146-147). At the same time that these changes were publicized, Tennessee's legislative apportionment, which had remained unchanged since 1901, was being challenged in federal court. This situation led to the landmark Supreme Court decision in Baker v. Carr, which ultimately led to more equitably divided districts. The legislature which repealed the Butler Act in 1967 was chosen under this new apportionment scheme, which increased urban representation at the expense of rural representation (Friborg, 1965, pp. 189-207; Murphy, 1972, pp. 384-391).

The decades following the passage of the Butler Act in 1925 witnessed several attempts to repeal Tennessee's antievolution law, none of which met with any success. Therefore, when the House of Representatives began considering yet another repeal attempt in early 1967, few observers were optimistic about its fate. Although the House passed the bill to repeal by a substantial vote of sixty to twenty-nine, it still had to go through the Senate, where more forceful opposition was expected (House Journal, 1967, pp. 553-554). While the Senate was considering the House bill, as well as a bill of its own to amend the Butler Act to allow the teaching of evolution as a theory rather than as a fact, a new variable was added to the debate when a science teacher in rural east Tennessee was dismissed for teaching evolution to high school students. This teacher, Gary Scott, with assistance from the American Civil Liberties Union and the National Education Association, soon brought suit challenging the constitutionality of the Butler Act. Scheduled for the federal district court in Nashville, this suit would feature the famous attorney William Kunstler as Scott's counsel (New York Times, April 15, 1967; Nashville Tennessean, April 15, 16, May 16, 1967; Knoxville News-Sentinel, April 15, 16, May 4, 5, 12, 13, 1967). Faced with the possibility of another evolution case in a Tennessee court, many senators ignored the continued opposition and eventually repealed the Butler Act in mid-May by a vote of twenty to thirteen (Senate Journal, 1967, pp. 862, 896).

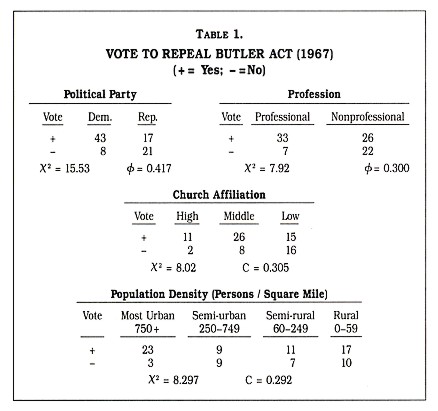

An analysis of the repeal vote in the House of Representatives, chosen because of its greater number of members, provides interesting data concerning the impact of various variables on voting behavior (Table 1, Tennessee Blue Book, 1967). Using chi-square methods to isolate variables for later analysis, no relationship stronger than 0.417 appears in the data. Party affiliation proves to be the strongest predictor of legislators' voting, with Republicans (except those from the most urban areas) more likely to oppose repeal and Democrats more likely to support repeal. This is a curious finding, because at no time was the Butler Act repeal a party issue and because there is no relationship between the rural or urban nature of a representative's district and party affiliation. Analyses of the rural or urban nature of districts, members' religious affiliations, and members' professional status all reveal measures of association near the 0.3 level. This indicates some degree of dependence, to be sure, but hardly sufficient to explain the repeal of the Butler Act in 1967.

The repeal of the Butler Act in 1967 can more convincingly be explained as a response to specific events related to the pending court case involving the statute and the perceived impact this case might have on the state's reputation. During televised Senate debate over repeal, one senator argued that others' perception of Tennessee did not matter. Referring to the sponsor of the Senate repeal measure, Ernest Crouch stated, "Senator Elam says we are being ridiculed in Europe. That doesn't bother me a bit. If those countries over there would pay us what they owe us, we could retire our national debt" (New York Times, April 21, 1967). Although not an isolated sentiment, this disregard for Tennessee's reputation was not shared by the majority of legislators, many of whom were concerned that the negative publicity which Tennessee was generating might jeopardize the state's ability to attract new industry and business. The possibility of yet another Scopes trial, this time with William Kunstler playing Clarence Darrow's role, must have filled many such "boosters" with dread. The best way to avoid the situation and to minimize the amount of bad publicity was to repeal the offending statute.

For the next six years, the evolution debate appeared to be over in Tennessee. When the Supreme Court declared Arkansas's antievolution law unconsti, tutional in Epperson v. Arkansas in 1968, followed by similar action in Mississippi courts in 1970, the place of evolution in the public school curriculum appeared to be secure. Such was not the case. In all but the most urban areas of Tennessee, evolution was largely ignored by public school teachers who were unwilling to overstep community norms which were frequently their own. Of greater ultimate importance, a new aspect of the evolution debate was becoming increasingly visible in the state. Through the work of Russell Artist, a biology professor at David Lipscomb College in Nashville, Tennessee, legislators were introduced to the creation-science movement during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Focusing upon the supposed scientific support for a literal reading of Genesis, Artist presented creationist alternatives to evolutionary explanations of the origin and development of life on Earth. Arguing further that the teaching of evolution in public school classes violated the religious freedom of fundamentalist students, Artist and other creationists campaigned for the inclusion of creationist accounts with evolutionary accounts in biology classes and texts. In this way, students could choose for themselves which version they wished to believe (Nashville Tennessean, April 30, 1973; May 10, 1981).

Tennessee responded quickly to this new antievolution argument. On March 26, 1973, a bill was introduced into the Senate requiring either the simultaneous teaching of evolution and creation or the teaching of neither. Recommended by the education committee and supported strongly by the fundamentalist Church of Christ, the bill appeared to have a very good chance of passage (Senate Journal, 1973, pp. 345, 599, 608).

Perceiving yet another antievolution law in Tennessee, concerned scientists and educators moved belatedly to influence the Senate to reject the creationist legislation. An ad hoc committee composed of professors from the University of Tennessee released a statement on April 17 which characterized the proposed law as "utterly repugnant to the American idea of democracy." Such statements had little impact on legislators, however, as evidenced by the reply of the bill's sponsor, Milton Hamilton of rural Union City. Dismissing the committee's statement, Hamilton said, "This is not a Ph.D. bill. It is a people's bill." Despite opposition from educators, the Senate bill moved toward a rapid passage. Senators quickly accepted two minor amendments and then passed the bill without debate and with only one dissenting vote (Nashville Tennessean, April 18, 1973).

The Senate bill was forwarded to the House, where it replaced a similar bill originally introduced on April 3. Representatives added four amendments to the bill: the first, limiting the restrictions in the act to biology texts; the second, allowing teachers to use supplementary materials to satisfy the requirements; the third, defining the Bible as a reference work; and the fourth, prohibiting the inclusion of occult theories. After a debate of one hour and twenty minutes, the House passed the "Genesis bill" by a vote of sixty-nine to fifteen, with fifteen representatives not voting. Among those who voted for the bill, many undoubtedly shared the sentiments of W. C. Carter of Rhea County, who had opposed the repeal of the Butler Act in 1967 and called the 1973 legislation "a remedy to a bad act" (House Journal, 1973, pp. 533, 844, 898, 1152; Nashville Tennessean, April 27, 1973). With the Senate's approval of the four amendments on April 30, the legislature sent the bill to Governor Winfield Dunn's office, where it became law at midnight, May 8, without the governor's signature (Senate Journal, 1973, pp. 1046-1049, 1301, 1527).

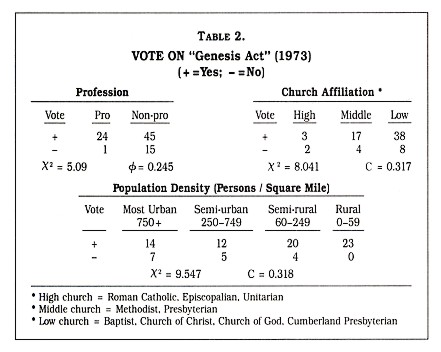

Because of the lopsided vote on the passage of the bill, an analysis of the legislature in terms of voting patterns must be viewed carefully. There are, nonetheless, interesting data to be found in such an analysis. Many variables, such as education and party, show no significant relation to voting behavior (Table 2, Tennessee Blue Book, 1973). Indeed, only professional status, religion, and constituency show any dependence patterns with voting behavior. Professional status shows a low measure of correlation, while rural-urban status and religion display a slightly higher correlation. Despite the uncertain nature of this data, it seems likely that demographic change played no stronger role in 1973 than it had in 1967.

A comparison of those legislators who voted on both bills reveals strong consistency, although only eleven members of the House are included in this group. Eight of the eleven voted in a consistent manner, voting to repeal the Butler Act and against the "Genesis Act" or vice versa. The three who voted inconsistently voted in favor of both bills.

A cursory examination such as this cannot possibly investigate all the possible influences on legislators' voting decisions or the relative strength of the variables isolated. From this study, it nonetheless appears clear that the legislative fortunes of evolution in Tennessee may not be explained solely in terms of the rural-to-urban shift which characterized the state's demography in the decades following Scopes. The increasingly urban nature of the state appears to have had only minimal impact upon attitudes toward evolution. Rather, the repeal of the Butler Act in 1967 is better explained as an aberration in this antievolution sentiment brought about by a number of unusual circumstances. These circumstances included the prospect of another Scopes trial and Tennessee's attempt to build a more favorable image in the hope of attracting new business and industry to improve the state's poor economy. Similarly, the 1973 "Genesis Act" can be explained as a partial return to the old order, with legislators seeing in creation-science a way to record their opposition to teaching evolution in the public schools. Such legislative action appears to support the hypothesis that opposition to evolution displays a great deal of continuity and that this opposition cannot be dismissed as a historical artifact of an earlier rural society.