"My understanding is that all the assertions in the Bible which pertain to science would be true."

-Robert V. Gentry

Cross-examination

McLean v. Arkansas, 1981

With the demise of the Paluxy River "mantracks," creationists lost a major portion of their already limited hard evidence for "creation science." As if to make up for that loss, they have been devoting increasing attention to Robert Gentry's writings on polonium halos. Gentry's work is of particular importance because, unlike typical creation "science," it involves actual field and laboratory work followed up by papers appearing in refereed scientific journals. This offers the kind of credibility sorely needed in the field of "creation research."

There is, however, a serious weakness in Gentry's work. It has been devoted almost entirely to the physics of the polonium halos, thereby neglecting the geological setting of the samples in which the halos are found. Because of this neglect, Gentry makes unwarranted generalizations about the nature of the world's Precambrian rocks.

The purpose of this article is to explain, as simply as possible, the geological setting of three of Gentry's sample sites and to show how each setting discounts Gentry's claims about the origin of Earth. I do not intend to discuss the physics side of the issue here. That subject would be more appropriate for another article taking into account the geological evidence outlined herein. Furthermore, a more detailed and technical treatment of the geological evidence has been submitted to the Journal of Geological Education.

Gentry's Basic Premise

Polonium halos are small spherical "shells" of radiation damage that surround radioactive inclusions within certain minerals in rocks. Gentry has described his work on and interpretation of these halos in a series of papers and in a 1986 book entitled Creation's Tiny Mystery. How these halos form is not difficult to understand. They are formed by alpha particles released during the decay of an isotope. As an alpha particle nears the end of its path and slows, it causes disruption of the crystal structure, leaving a small damage track. Over time, repeated decays from the parent isotope will leave a spherical halo of discoloration. The distance that an alpha particle travels depends upon the energy of the decay and that, in turn, is a function of the particular nuclide that decays. Theoretically, then, the radii of a series of halos that surround a radioactive inclusion permit identification of the specific decaying nuclides.

Gentry has claimed that certain of these halos indicate that the granite "basement rocks" of Earth are "the primordial Genesis rocks" and were created instantaneously about six thousand years ago. Essentially, Gentry has found that in certain samples of Precambrian biotite (a mica) the inner ring halos for uranium and other nuclides in the decay chain which should be producing Polonium 210, Po214, and Po218 are missing; only the polonium rings for these three isotopes are present. In addition, Gentry observed little or no uranium in the radioactive inclusion. His conclusion is that the polonium must have been primordial and, because of the short half lives of the polonium isotopes (138.4 days, 0.000164 seconds, and 3.04 minutes, respectively), the granite, therefore, must have been created in the solid state in "only a brief period between 'nucleosynthesis' and crystallization of the host rock" (Gentry, 1975, p. 270).

In his scientific literature, Gentry has avoided making direct creationist statements, but from the above and other statements one gets the distinct impression that Gentry is trying to link the rocks of the Precambrian to the rocks that existed right after Earth's formation—or creation. For example, Gentry states: "It is also apparent that Po halos do pose contradictions to currently held views of Earth history" (1974, p. 63); "The Question is, can they be explained by presently accepted cosmological and geological concepts to the origin and development of Earth?" (1974, p. 66); and "Do Po halos imply unknown processes were operative during the formative periods of the Earth?" (Gentry, Hulett, Cristy, McLaughlin, McHugh, and Bayard, 1974, p. 564)."

His book, however, is far more bold than are his refereed papers. Comments such as the following are common in Creation's Tiny Mystery:

Were tiny polonium halos God's fingerprint in Earth's primordial rocks? Could it be that the Precambrian granites were the Genesis rocks of our planet?

[p. 32]

. . . polonium halos in Precambrian granites identify these rocks as some of the Genesis rocks of our planet-created in such a way that they cannot be duplicated without intervention of the Creator.

[p.133]

In the young-Earth creationist perspective, this puts Gentry in essential agreement with John Whitcomb and Henry Morris (The Genesis Flood, p. 228) in claiming that the Precambrian is the created rock and of granitic composition. This is an overly simplified view of the complex Precambrian terrains of the world, and it is simply not true that Precambrian rocks are those left from Earth's formation. Far from it! They are rocks formed by the same or similar process that formed the post-Precambrian rocks. The only significant differences are: (1) fossils are rarer in Precambrian rocks, and (2) many Precambrian rocks have had more complex histories because they are much older.

Geology of the Canadian Sites

The Precambrian is divided into two main eras: the Archean, containing the oldest Earth rocks, from 3,800 million years ago to 2,500 million years ago; and the Proterozoic, from 2,500 million years ago to 700 million years ago. Before knowing Gentry's specific sites, I imagined that he had taken his Canadian samples from the area geologists call the "Superior Province," located in northern Ontario. I thought this because the Superior Province is of Archean age and contains the oldest rocks in North America. You can therefore understand my surprise when I learned that Gentry's sites were in the much younger (as dated both radiometrically and structurally) late Proterozoic Grenville Supergroup of the Grenville Province. Louis Moyd of the National Museum in Ottawa brought this point up when Gentry visited the area in 1971 to collect samples (Moyd, 1987). Because Gentry lumps most of the Precambrian rocks into one unit—the created one—it is apparent that he knows little about Precambrian geology.

The reason my first assumptions on the location of Gentry's sites were wrong was because he has not been as clear as he should be in his writings. In his book, Gentry specifically names only one site, the Silver Crater Mine. Other sites are discussed in a general way as being in Madagascar, New Hampshire, and Norway, but this is unsatisfactory. He should have given exact and formation names for each sample. This lack seems strange in a book whose avowed purpose is to explain and to justify his claims. This tendency toward generalized descriptions of his sites appeared also in his 1967 article in Medical Opinion and Review, in which he mentioned halos he found "in the Wolsendorf (Bavaria) fluorite."

For more specificity, I had to turn to Gentry's papers in Nature (1974) and Science (1971), in which he mentioned the Silver Crater Mine and the Faraday Mine. I then discovered that both are only a two-hour drive from my home. The location of a third site, the Fission Mine, I found by asking Louis Moyd. Nowhere does Gentry describe it, but, like the other two, it is also within the rocks of the Grenville Supergroup. All three sites are near Bancroft in southern Ontario.

The Grenville Supergroup is a very complex succession of metasediments (cooked sedimentary rock), metavolcanics, alkalic intrusive rocks, mafic intrusive rocks, and granitic intrusive rocks. It is located in a region of low-grade to very high-grade metamorphism that has altered many of the igneous, sedimentary, and volcanic rocks into recrystallized gneisses. However, many original igneous, sedimentary, and volcanic features are preserved. Hydrothermally altered rocks are also common as well as metasomatic rocks (wall-rocks that have been included into and altered by intrusive melts). The metavolcanics, the lowermost rock units in the Supergroup, consist of pillow lavas (indicative of underwater extrusion), breccias (fragmented lavas), tuffs, and pyroclastics (similar to what came out of Mount St. Helens) altered to varying degrees by metamorphism. The intrusive rocks consist of quite varying types, such as gabbros (a dense rock high in the mafic minerals which contain iron and magnesium), granites (light-colored rocks low in mafic minerals but high in potassium and sodium silicates, such as feldspar and quartz), diorites (intermediate in composition between the former two), syenites (poor in quartz), nepheline syenite (like syenite but higher in alkali metals), and pegmatites (any of the above in small dikes with large to very large crystals). Many, but not all, of these intrusive rocks have been altered by low-grade metamorphism.

The minerals in which Gentry found polonium halos are biotite and fluorite. Biotite, of the three types of mica, is a hydrous-potassium-mafic-aluminum-silicate which forms sheets in the crystals. It is a very common rock-forming mineral and is found in many of the different Precambrian rock types of Ontario and elsewhere. Fluorite is calcium fluoride. It forms various colored cubic crystals and is a common vein mineral. Let's examine the specific geology of the three sites.

The Fission Mine

The Fission Mine (also known as the Richardson Mine) is located two kilometers east of Wilberforce on lot four, concession twenty-one, of Cardiff Township. It consists of a single abandoned tunnel driven into a hill. This site is a common mineral-collecting locality for apatite, biotite, radioactive minerals, and fluorite. From Gentry's description, it appeared that his fluorite and some of his biotite samples came from this mine. But in a phone conversation he told me that the fluorite samples came from Germany. Nevertheless, Moyd indicated to me that samples from the Fission Mine were sent to Gentry. The following geological description of this site is from the International Geological Congress Guidebook Field Excursion A47-C47:

The country-rocks are variably syenitized biotite-gneisses and amphibolites, underlain by a thick series of partly silicated marbles. The altered gneisses are of many types. . . . The main deposit consists of a series of closely spaced vein-dikes. . . . Most of the vein-dikes are more or less conformable with the structures of the enclosing gneisses, but some transect these structures. The bodies are extremely irregular in shape, thickness, and extent. Some of the individual vein-dikes exceed 300 feet in length, with maximum thickness of more than 10 feet.

Last in this sequence [of rock units] are the vein-dikes, in which the core zone constitutes a substantial proportion of the whole mass. The bodies are generally more or less tabular, with crystals projecting inward from the walls. Some of the crystals are partly cavernous and enclose semi-isolated masses of the core-materials. Others may be more nearly euhedral, but contain completely isolated, rounded pellets of core-minerals . . . calcite, fluorite, or mixtures of both.

The composition and structure of these vein-dikes indicate origin by hydrothermal "fluxing" and recrystallization of wall rocks along bedding planes, joins and other fractures. The abrupt termination of the vein-dikes . . . strongly favours such an origin—the hanging wall [top of dike] curving around to become the foot-wall [floor of dike].

Uraninite occurs as cubic crystals and also as irregular masses. It is very erratic in distribution and can be found in various associations. . . .

Most fluorite is the deep purple variety, antozonite. . . . smells of fluorine and ozone when crushed or abraded, all of which reflect radiation damage. The depth of colour of the fluorite is an indicator of the proximity of uraninite.

[Hogarth, Moyd, Rose, and Steacy, 1972]

From this description, it is clear that we are dealing with intrusive calcite vein dikes (rocks containing mostly the mineral calcite and other minerals, such as mica) that are small in length and width and cut metasedimentary rocks which still retain bedding planes. Radioactive minerals abound in this locality. Percolating water from the hill the deposit occupies is strongly radioactive and was sold in the 1920s for therapeutic purposes. Hornblende crystals two meters long, biotite thirty centimeters across, apatite thirty centimeters long, feldspars one meter long, and zircons five centimeters long have been seen in this deposit.

The Silver Crater Mine

The Silver Crater Mine (or Basin Mine) is located twelve kilometers west of Bancroft and three kilometers north of the settlement of Monck Road on lot thirty-one, concession fifteen, of Faraday Township. Like the Fission Mine, it also consists of a single abandoned tunnel driven into a hill. This is where the mica, like the one that contains Gentry's "spectacle" halo which "exhibits true radiohalo characteristics," came from.

This site is related to the Fission Mine, and it, too, is a calcite intrusive of the same origin. Here are some quotes from the Ontario Department of Mines (now the Ontario Geological Survey) report for 1957, written by D. F. Hewitt, on the geology of the site:

The [calcite vein dike] body consists of a coarse-grained calcite (1-5 inches in size), containing accessory black mica (lepidomelane [high mafic biotite] ) in books up to 2 feet in diameter. . . .

This deposit has some features characteristic of the metasomatic replacement deposits in marble, of the hydrothermal calcite-apatite-fluorite vein deposits, and of intrusive carbonate deposits. Its mode of origin is in dispute.

The coarse pegmatite crystallization of the calcite, black mica, hornblend, and albite suggest crystallization from a fluid medium, rich in volatiles. . . . The wall-rock alteration, involving addition of fluorine, carbon dioxide, and soda into the surrounding wall-rock, favours crystallization of the [calcite vein dike] body from a fluid state, such as a carbonate intrusive or hydrothermal solution. . . .

. . . The irregular replacement of the wall-rock gneiss and the long relic bands of biotite amphibolite in the [calcite vein dike] indicate metasomatic replacement of the wall-rock gneiss by [carbonatite].

The author believes that the [calcite vein dike] has originally been largely derived from marble but that it has been assimilated or desolved and recrystallized from hot solutions rich in fluorine and soda. This would account for the extensive wall-rock alteration and the metasomatic type of replacement of wall-rock gneiss, without disturbance of relic mafic gneiss bands. Such relict bands are incompatible with an origin of the [calcite vein dike] body involving tectonic movement of a marble bed in a plastic state. The author feels that the deposit is therefore best classed as a special variety of the hydrothermal deposit in which the solutions have carried out extensive metasomatic replacement of the wall-rocks.

[pp. 77-78]

From this we learn that the calcite vein dikes are intrusive into and thus formed later than the country rock that makes up the formation. They have also altered the country rock.

But now something needs to be made clear. The Silver Crater and the Fission Mines are not granites. The composition and mode of origin is totally wrong for a granite. In identifying them as granites, Gentry has made a major error. In his book he erroneously criticizes Dalrymple for making a comparison between the textures of basaltic lava and granite (p. 130); yet, he himself cannot tell the difference between granite and calcite vein dikes.

There is a consensus from more recent research about the origin of the carbonatite material that formed these dikes and on the origin of the biotite and other large minerals in the dikes. Because of the presence of rounded calcite in the minerals themselves, it is thought that the biotite grew as a replacement within the solid calcite vein dike matrix. This process occurs when the solid calcite vein dike, which was hydrothermally deposited or injected as a molten liquid, is reheated enough to cause the evenly distributed minerals of biotite, hornblende, betafite, apatite, and so forth, in the wall rock and calcite vein dike to start to migrate and form larger crystals in the carbonatite.

Gentry made the claim that "halos occur in many mica samples which have not undergone metamorphism of any kind" (1986, p. 299). However, these micas were indeed formed during metamorphism under the load of moderate-depthed overburden, which has since been eroded off. Let me state it another way—the biotite was metamorphically derived.

The Faraday Mine

The Faraday Mine (now called the Madawaska Mine) is located five kilometers west of Bancroft on Highway #28 on the northeast end of Bow Lake. The mine was opened for the high uranium content in a granite pegmatite which cuts a gabbro-metagabbro intrusive body which itself cuts metasedimentary rocks, including marble. Jack Satterly mapped the Bancroft area for radioactive minerals in the early 1950s. Here are some quotes from Satterly's Ontario Department of Mines report for 1956 on the geological setting of the Faraday Mine:

The radioactive minerals occur in bodies of leucogranite, leucogranite pegmatite, and pyroxene granite (or syenite) pegmatite, cutting metagabbro and gabbroic amphibolite. The metagabbro and amphibolite form the western part of the Faraday metagabbro, a metamorphosed basic intrusive body about 6 miles in length and up to 3/4 mile wide, which cuts the Grenville metasediments, chiefly marble, amphibolite, and paragneiss, in this area. Inclusions and relict bands of marble and metasedimentary amphibolite occur in the metagabbro. The Grenville metasediments and the Faraday metagabbro are intruded by nepheline syenite, syenite and granite. . . . the metagabbro itself is strongly affected by dynamic metamorphism and shearing.

Structurally, the granitic [pegmatite] bodies of the Faraday mine intrude the metagabbro, which lies in the mixed hybrid gneiss zone that forms the hanging wall of the Faraday granite sheet. These bodies may be related genetically to the latter intrusive.

[p. 110]

In other words, material was eroded from some preexisting rock, deposited as a sedimentary rock, then deformed and recrystallized by high-grade (high temperature and high pressure) metamorphism, which altered the rock to what is called gneiss. This, in turn, was intruded by the gabbro, which later underwent another metamorphic episode. Finally, these rocks were intruded by the granite pegmatite. Gentry's biotite came from this pegmatite, which he acknowledges.

S. L. Masson and J. B. Gordon note of the pegmatites of the mine:

They generally conform to foliation but locally cross-cut it. Pegmatites masses are 91.5 to 915 m long, 3 to 46 m wide and some extend down dip more than 300 m. . . . The pegmatite is composed of feldspar, hornblend-chlorite, quartz, calcite, magnetite, and zircon. Main accessory minerals are [biotite] mica, titianite, apatite, allanite, tourmaline, uraninite, uranophane, and uranothorite.

[p. 60]

A. R. Bullis, writing on the geology of the pegmatites of the mine, concluded:

It is obvious that both injection and metasomatic processes have taken place during the intrusion of the pegmatites. Chilled edges are rare or nonexistent. Magmatic stoping, or the engulfing of the country rock has taken place on a large scale; there are many blocks of paragneiss and pyroxenite within the pegmatite. Most of the inclusions are fresh looking, but many are highly altered and ghost-like in appearance.

[p. 717]

The Faraday Mine pegmatites have been dated at between 992 million years to 1,088 million years by several methods (Easton, 1986a; 1986b). Though no dating of the Faraday gabbro has been done, other gabbros in the area of similar composition, such as the Tudor Gabbro, have been dated at 1,240 million years (Easton, 1986a). The Silver Crater deposit has been dated at 1,000 million years (Galt, 1987) and the Fission Mine is closely related in age.

The interesting thing about Gentry's work is his claim that there is no uranium or thorium in the nucleus at the center of the polonium halos:

Application of [special acid technique] to regions of mica near polonium halos showed only evidences of trace amounts of uranium (a few parts per million) that exist throughout all mica specimens—there was no concentration of uranium in or near the halo centers in the clear areas.

[1986, p. 31]

This is very difficult to accept since the Faraday pegmatite was mined for uranium. A total of some four million tons of U3O8 ore were mined for a total of 7.3 million pounds of uranium oxide up until the mine's closure in 1984. The average concentration consisted of 0.1074 percent uranium oxide. The most common radioactive mineral is uranothorite, hence lots of uranium and thorium. These minerals are very small (less than one-tenth of a millimeter) and scattered throughout the pegmatite, becoming ore grade in the quartz and magnetite regions of the pegmatite.

The Silver Crater and Fission Mines are lithologically different, but they, too, contain abundant radioactive minerals—especially betafite, a radioactive variety of the mineral pyrochlore, which is a complex calcium-sodium-(uranium)-niobate-tantalate-hydroxide. It was noted by Satterly that "Betafite [at the Silver Crater]

is often found in close association with clusters of mica books and apatite crystals. Small crystals of betafite have been found within the books of mica" (p. 130; emphasis mine). In my phone conversation with Gentry in February, he admitted the betafite was with his samples. Why did he leave that observation out of his papers? Why is it, with so many radioactive minerals and so much groundwater at these sites, that there is very little uranium in the halo centers? Or is there? Did Gentry err? Clearly, there is something complicated going on here, considering the nature of the host intrusive rocks, the low-grade metamorphism that the intrusive rocks have undergone, the high-grade metamorphism of the surrounding wall rock, the hydrothermal activity and the metamorphic replacement by the biotite within the calcite vein dikes. Gentry noted that "the great majority of minerals containing polonium halos show no evidence of high temperature episodes" (1975, p. 270). Gentry also noted in that same paragraph that "halo coloration disappears within minutes in [the 300 degree Celsius] temperature range" for fluorite. He continued:

An equally strong objection to the uranium-daughter hypothesis in uranium poor (p.p.m. or less) minerals is that many Po halos (such as the `Spectacle' halo [from Silver Crater]) are located in the interior of large pegmatite crystals as well as in small granitic mica flakes where they are often more than 10 cm. and sometimes much less than 100 cm. away from a significant uranium source.

[1975, p. 270]

This is quite an extraordinary claim to make for four reasons: (1) it contradicts Satterly's observation of betafite within some of the biotite; (2) it shows that he knows it is a pegmatite body and therefore must be intrusive; (3) it admits that heat, such as that from a metamorphic event, erases halos; and (4) it acknowledges the proximity of radioactive minerals.

In our phone conversation in March, Gentry claimed that the sedimentary rocks cut by the dikes and pegmatites are "pristine"—that they were created during creation week—and that some of them were later reworked during the Flood. He gives us a time-frame for all this to occur in his book:

The Creator, after calling the chemical elements into existence, might well, in the next instant of time, have formed those elements into a liquid, and then immediately cooled that liquid so that it crystallized into the granites containing the polonium halos. These granites would have been created instantly and yet still show the characteristic of rocks that crystallized from a liquid or melt.

[1986, p. 129]

Was then, the halflife of 218Po—just three brief minutes—the measure of time that elapsed from the creation of the chemical elements to the time God formed the granites?

[p. 32]

The question I ask is why did Gentry choose Po218's halflife of 3.04 minutes for this "measure of time" and not Po210 at 138 days or Po214 at 0.000164 seconds? Was this choice rationally, arbitrarily, or biblically based? Regardless of which one, this is an Omphalos argument. In fact, a look now at the whole shield will indicate how much must have been created with the appearance of age.

Precambrian Geology and Instantaneous Creation

A great deal of work has been carried out on the Precambrian Canadian Shield. The shield is made up of seven distinct geological provinces—the Bear, the Slave, the Churchill, the Superior, the Southern, the Grenville, and the Nain—west to east from the Northwest Territories to Quebec in an arc around Hudson Bay. Ontario, where Gentry's samples came from, has three of these provinces. The Superior, situated in northern Ontario, is the oldest (all isotopic ages are greater than 2,500 million years and hence is Archean) both radiometrically and structurally and consists of many types of metasediments and several types of metavolcanics intruded by a variety of igneous bodies. The Southern province, which rests unconformably (with fossil soil) on the Superior, is mostly folded metasediments intruded by some granites and is middle to early Proterozoic (all isotopic ages are between 2,500 and 1,800 million years) in age. The Grenville, located in southern Ontario, the youngest province, is late Proterozoic (all isotopic ages are 1,500 to 900 million years) and is made mostly of contorted metasediments in the north, a large metamorphosed intrusive gneiss complex (called the Algonquin Batholith) in the middle, and the Grenville Supergroup in the south. The latter, which contains Gentry's locations (mentioned earlier), consists of metasediments (mostly metamorphosed limestone which is marble) and matavolcanics all intruded by igneous bodies of various types.

Gentry's Faraday samples came from a pegmatite dike that cut a gabbro, which cuts different types of metasedimentary rocks. These metasedimentary rocks can be shown in the field to rest in a complex way on metavolcanics around the Madoc area south of Bancroft. This, in turn, rests unconformably on the metamorphosed Algonquin Batholith, which intrudes the deep and shallow water metasediments to the north, which abuts (by a major fault) and partly rests on the metasedimentary column of the Southern province, which rests unconformably on the "greenstone" metasediments and metavolcanics intruded by granites, which abuts the metasedimentary and gneissic belts to the north in the Superior province.

Let me emphasize that these relationships are not primarily based upon the "uniformitarian principle" but on hard-won field observations over almost one hundred years by hundreds of geologists. So, if Gentry's claim of created granite is valid, then this entire elaborate geological sequence must have also been instantly created in twenty-four hours; it only appears to have formed over a long period of time. This is the Omphalos argument again.

What is also interesting is that Gentry has been reminded in the past, in a general way, that granites are intrusive rocks and that the oldest rocks on Earth are sedimentary and volcanic (Awbrey, 1987; Dalrymple, 1986; Wakefield, 1987). Gentry sluffed off the comments or claimed he had an explanation but didn't supply it. Now, in his book he writes of "pristine sedimentary" created rocks which look as though they were intruded by granites:

. . . the Genesis record of creation week and the subsequent events of the world-wide flood encompass, in addition to the primordial created rocks such as the Precambrian granites, the formation of pristine sedimentary rocks, lava-like rocks, the intrusion of granite-like rocks into pristine sedimentary rocks, and almost unlimited possibilities of mixing these various rock types with the secondary rocks that were formed at the time of the flood. . . . That model includes the possibility that some granites may have been created on Day 1 adjacent to and immediately after some primordial or pristine "sedimentary" rocks were created.

[1986, p. 302]

When Gentry phoned me after he was sent a copy of this article in preliminary form, I asked him about the sedimentary rocks. He claimed that metasedimentary rocks show no clear origin because of their recrystallization. This is totally wrong and I pointed out that many of these metasedimentary rocks show clear and unambiguous sedimentary features, such as clastic grains, cobbles, ripple marks, mudcracks, bedding plains, and, most important, stromatolites. He made no reply.

In the phone conversation I had with Gentry in March 1987, he claimed that all of the rocks of the shield could have been formed on the first day of creation. Here are some excerpts from his book on this point:

. . . only a few minutes elapsed time from nucleosynthesis to the formation of the solid earth. . . . a virtually instantaneous creation of the earth.

[1986, p. 49]

These [polonium-containing] granites would have been created instantly and yet s, till show the characteristic of rocks that crystallized from a liquid or melt.

[p. 129]

. . . The primordial Earth being called into existence on Day 1 of creation week about 6000 years ago. . . . the Precambrian granites show evidence of an instantaneous creation. . . .

[p. 184]

. . . the Precambrian granites are identified as rocks that were created almost instantly as part of the creation event recorded in Genesis 1:1.

[p. 280]

Since his dikes are demonstrably the last rocks to form in the shield, then, by his reasoning, the entire shield must have been "instantly created." However, he acknowledges that it would take close to twenty-four hours.

Crystal Sizes and Pegmatite Dikes

On pages 130 and 131 of his book, Gentry presents his criteria for identifying the created granites. He explains, in trying to rebut Dalrymple's testimony at the trial (McLean v. Arkansas), the difference between Hawaiian lava and Precambrian granites. Dalrymple was comparing the type of crystal structure of solidifying basaltic lava and extrapolating on how deep granite would solidify. However, Gentry says the comparison of lava and granite is erroneous because they are grain-sized and mineralogically different.

In bulk composition and mineralogy the lava specimens are olivine-rich basalt, grossly different from any granite. . . .

The Kilauea-Iki samples are fine-grained. . . . The Precambrian granites, on the other hand, are generally characterized as being coarse-grained. . . This means the only similarity between granites and the lava specimens is the interlocking, intergranular arrangement of the crystals making up the rocks. This characteristic can be accounted for naturally by slow cooling of the lava in the case of the Kilauea-Iki specimens—or by rapid or instantaneous cooling from a primordial liquid in the case of the granites.

It is a fact that a hot fluid rock, such as that produced at Kilauea-Iki, can cool over a period of a few years to form fine-grained volcanic rocks composed of microscopic-sized crystals. The same is true of rocks that form when granites deep in the earth are melted. The granite melt may extrude onto the surface and cool rapidly to form a glassy rock; or it may cool more slowly beneath the surface to become rhyolite, a fine-grained rock. . . . Both the glassy rock and the rhyolites are intrinsically different from the coarse-grained granites.

[1986, p. 130]

Unfortunately, Gentry botches this whole argument by not realizing that there are many types of igneous rocks. This is quite evident since he misidentified a type of igneous rock; he says that rhyolite is a natural form of granite that forms at depth very slowly and that rapid cooling results in a glass (I suspect he is referring to obsidian). He said, "Both the glassy rock and the rhyolites are intrinsically different from the coarse-grained granites." To emphasize this point, he compares in his book a drill-core sample of rhyolite taken from a depth of 1,683 feet at Inyo Domes, California, to a sample of medium-grained granite. His point is that crystal size determines the formation of the rock: coarse-grained granite is supernaturally and instantaneously created; whereas fine-grained rock is intrusive and glassy rock is extrusive. It was obvious to me that Gentry was having a hard time with this part. Did you note his error on the rate of lava cooling for rhyolite?

There are two types of igneous rocks: extrusive, such as flows, and intrusive, such as dikes and plutons. Rhyolite is an extrusive equivalent of granite by definition! The composition is exactly the same. The sample Gentry provides as an intrusive rhyolite is in fact a conduit which fed a volcanic flow at the surface (Dalrymple, 1987; Eichelberger, 1984). It is suspected that the texture of the glassy rock which Gentry mentions, the obsidian, is dominated by lack of water, not temperature, in its formation. In fact, at that site it can be shown that the rhyolite cooled first. The water content of the rhyolite is higher, and it is suspected that, at considerable depth, the texture is more granitic due to even higher water content (Eichelberger, 1987).

Sixteen hundred eighty-three feet is not very deep, and hence the "rhyolite" definition for the conduit is correct. The term granite is suited for much deeper—for example, greater than two kilometers—intrusions of the same composition rock as rhyolite. That is why this rhyolite of Gentry's is fine-grained; it cooled quickly near the surface. He got the notion of a glassy rock from one particular type of volcanic flow at this site, which is not indicative of volcanics in general.

Gentry shows his lack of geological understanding in claiming that granite and basalt cannot be used for comparison because they are mineralogically different. If it is composition that Gentry wants to compare, I would compare rhyolite and granite; if it is grain size that Gentry wants to compare, I would compare rhyolite to gabbro. Gabbro is a large-grained intrusive rock, just like granite, with the same crystal structure and size, but its composition is the same as basalt.

Gentry made several other errors simply because he did not understand enough geology. He says that "the tiny crystals of which rhyolite is composed bear no comparison in size to the very large crystals found in certain regions within granites known as pegmatites. . . . (Most of the polonium halos in mica . . . were found in specimens of biotite taken from pegmatites)" (1986, p. 131; emphasis mine). Well, there you have it. He has sunk his own argument! Pegmatites, as noted in the three site examples, cut other rock units.

What Gentry is trying to say is that large crystals do not form in nature and so require a supernatural origin. But he is wrong. The intrusive rocks in the shield show a wide variation in grain size. For example, the Addington Pluton, near Kaladar, south of Bancroft, is fine-grained but contains stringers of coarse-grained quartz and some biotite. Many of the dikes in the shield are coarse-grained pegmatites, but some are fine-grained.

It would help at this stage to define a pegmatite:

Pegmatites represent the final water-rich, siliceous melts of intermediate to silicic igneous magmas, and can generally be thought of as final residual melts. . . .

Although pegmatites can be found in almost any shape, they are most commonly dikelike or lensoid. Most pegmatites are small, but dimensions can vary from a few meters to hundreds of meters is the longest dimension and from 1 cm. to as much as 200 meters in width. . . . Since igneous pegmatites characteristically solidify late in igneous activity, they tend to be associated with plutonic or hypabyssal intrusions from which the volatile fractions could not readily escape. The great majority of pegmatites developed in deep-seated high-pressure environments.

[Guilbert and Park, 1986, p. 488]

There are many types of dikes which cut the other rock units of the shield. The most common of these in northern Ontario are diabase dikes, which are found in very large clusters called dike swarms. Diabase dikes are narrow (from centimeters to many tens of meters) and very long (kilometers to hundreds of kilometers). Some dikes are fine-grained at the contact with the wall-rock, grading to coarse-grained in the center. In the Sudbury area, some of these dikes are known to cut through over thirty other rock units. In the Archean area of the shield, at least four different sets of different-aged diabase dikes cross-cut each other.

Many of the pegmatite dikes commonly show clear mineralogical zoning from the edges to the core of the dike. In Quadville, just east of Bancroft, a pegmatite body is zoned with feldspar, filled with very large crystals of beryl, at the edges to massive quartz at the core. Some dikes have pyrite, copper, or gold mineralization—the last to form—right in the middle. Some dikes have a clear-cut, or chilled, contact with the wall-rock, while others have a gradational contact because heat of the intrusive dike partly melted the wall-rock. This occurs, for example, in the pegmatite at the Faraday Mine. And some of the dikes are vein-dike types deposited in cracks or cavities by fluids. This is the case with the Fission and Silver Crater Mines.

If the criterion for distinguishing a created rock from a naturally crystallized rock is grain size, then at what grain size is that distinction possible? The grain size of dikes ranges from microscopic to several tens of centimeters. In one pegmatite dike near Madawaska, north of Bancroft, which was mined for feldspar, a single crystal measuring seven meters long and weighing three tons was extracted. At the Silver Crater Mine, hornblende crystals three meters long have been observed. I've seen crystals the size of your fist on Turner's Island, east of Bancroft. These are all in cross-cutting dikes and are clearly intrusive.

Porphyries pose another serious problem for Gentry's interpretation. These are found in volcanic flows or as dikes with large crystals (called phenocrysts), up to centimeters long of a single mineral set in a very fine-grained matrix of the same or other minerals. How would Gentry explain this? Geology can easily explain these rocks. Different minerals melt at different temperatures. So, as a magma chamber cools, the highest melting point minerals crystallize first. If, at some time, the magma mobilizes to a different location while the first solid mineral is still suspended in the liquid and injected as dikes and sills or extruded as flows, then the remaining magma will cool too quickly to form large crystals and the phenocrysts will be trapped in the fine-grained-size matrix.

Igneous rocks come in a variety of grain sizes, and the principal factor that controls grain size is the cooling rate: slow cooling results in large crystals; fast cooling results in small crystals; and very rapid cooling results in glass. This has been known to geologists and chemists for more than a century and can be demonstrated in the laboratory. Gentry is simply wrong in his conclusions about the importance of grain size.

Sequence of Rock Formation

I confronted Gentry with the information about dikes by sending him some of the references and through subsequent phone conversations with him in February, March, and April 1987. In a phone conversation with him on April 12, he told me that the sequence of events in the area was not what I had told him it was but that the intrusive rocks were first and the sedimentary rocks were last to form. What made him the most anxious were the stromatolitic horizons recently found just south of Bancroft in the marble units cut by the Faraday gabbro and pegmatites. He challenged the fact that they exist. However, there is no question as to their authenticity (Easton, 1987).

I explained that there were features that show conclusively the sequence of rock formation from basaltic flows, thirty kilometers to the south near Madoc, followed in a complex way by the sedimentary rocks, succeeded by the intrusion of the gabbro plutons and, finally, the pegmatite intrusive bodies. In fact, I collected samples from this very sequence and sent them to him with a description. During our conversation on April 12, he challenged that sequence by claiming that it was not a vertical sequence but, rather, over a large distance. I told him the sequence had been tilted on its side. He still did not appreciate this sequence.

I argued that the nature of the intrusive rocks is very conclusive. Features include contact metamorphic recrystallization of the sedimentary rocks by the heat of the intrusive body. He claimed that the recrystallization was not due to the molten intrusive rock but, since the intrusive rocks were first, was caused by some sort of chemical alteration of the sedimentary rocks.

I explained to him that the intrusive rocks, including the pegmatites, show little or no regional metamorphic alteration but that the surrounding sedimentary and volcanic rocks are very much cooked. Thus, the intrusive rocks must have been implaced after or very near the end of the metamorphic event. I had to explain what regional metamorphism was (alteration of large areas by heat and pressure). He had no answer to that.

I described to Gentry another conclusive evidence of intrusion. There are pieces of sedimentary rocks enclosed within the intrusive rocks, engulfed and surrounded by the melt. The earlier comments on the Faraday Mine describe some of these features. I asked him how, if the metasedimentary rocks were younger than the intrusive rocks, he felt these inclusions got into the solid rock: Gentry denied the existence of these inclusions, but their occurrence is described in the literature I had already sent him. Now he acknowledges their existence but denies their implications. In addition, these inclusions are very common and descriptions of them occur throughout the geological literature of the shield, which Gentry either has not read or does not understand.

An Unexpected Visit

During October 1987, Walter Brown was in Ontario. During his seminar at the University of Waterloo, where Brown presented the polonium halos, I pointed out the preceding information about the geology of the sites. Brown was interested in seeing the rocks for himself, and we made arrangements to go to Bancroft. I asked Hans Meyn, the resident geologist in Bancroft, if he would join us, to which he agreed. We arranged to meet at Meyn's office on October 29.

Just as Brown, Meyn, and I were about to set off, Brown asked if Robert Gentry could come along. He said that he had been planning to show Gentry the sites after we showed him around but that, due to a lack of time, Gentry, who had flown in the day before at Brown's request, should join us. At first I thought this a joke, but to my surprise Gentry indeed was waiting at a nearby house.

The first place we visited—and it is the most important here—was the stromatolite occurrence at L'Amable. Gentry appeared unimpressed, especially when it was noted that these structures were metamorphosed and, thus, all traces of organic remains were removed. To Gentry, this was enough to not make them stromatolites. When pressed as to what, then, he believed them to be, his response was to the effect that in looking up at the stars at night it was obvious that God made some wonderful and mysterious things in the universe. These "features," to Gentry, were just one of these great created things! As far as Gentry is concerned, there are no sedimentary rocks in the shield because they have been metamorphosed and contain no fossils. To him, a truly sedimentary rock, formed during the Flood, must contain fossils.

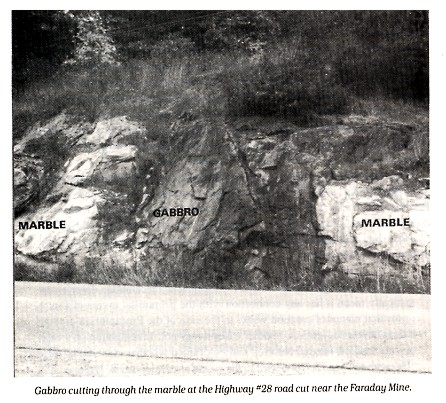

We also visited the Faraday Mine's main pit to look at the pegmatite cutting the gabbro and at the gabbro cutting the marble at the Highway #28 road cut.

The intrusive contact of the gabbro into the marble and the metamorphic alteration of the marble were obvious. So was the pegmatite cutting the gabbro at the mine. At this point, Gentry reversed his stand that the intrusives were first, now claiming that the intrusive nature, which was blatantly obvious, fit his twenty-four-hour creation model. But for this to be so, he had to conclude that the metamorphosed sedimentary rocks were part of the creation. When pressed about the primary sedimentary features still preserved, he just claimed that they were not.

I also asked him directly at what crystal size could he determine the origin of the rock—that is, created or natural—because the crystal size grades from microscopic to pegmatitic in the rocks in this area. He did not give a direct answer but urged Meyn to read his book, saying that it explains everything.

It became obvious that there was no way that Gentry was going to agree with us, and we ended our short visit.

Conclusion

What have we learned? Let me summarize.

First of all, the samples of biotite that contain Gentry's polonium halos came from pegmatite dikes and calcite vein dikes which cross-cut metamorphosed volcanic, sedimentary, and igneous rock units. The dikes are clearly the last to have formed, not the first. Second, these dikes are not the vast, extensive granite gneisses which Gentry claims are the backbone of the mountains and continents; they are relatively small features. Third, two of Gentry's sites are not even granites but calcite vein dikes, most likely of hydrothermal origin. The biotite was formed in the solid matrix by metamorphosis. And fourth, crystal size in igneous, vein, and meta morphic rocks ranges from microscopic to very large, is primarily due to cooling rates, and cannot be used to identify "created" rocks.

So, the "basement rocks" in which Gentry found his halos turn out not to be "basement rocks" at all. In fact, they appear in rocks that formed much later than Earth's oldest rocks. This fact alone tells us that the rocks bearing Gentry's halos, even if instantly created, have no bearing on the origin and age of Earth.

Realizing how serious this problem is, Gentry has been forced to turn the science of geology upside down:

. . . just because geologists designate something as Precambrian doesn't automatically mean it has any connection with the primordial events of Day 1, or for that matter of creation week. In the case of the Precambrian granites it does have a connection; in other cases it may not. Investigation on a case-by-case basis is needed before it can be decided whether something called "Precambrian" can be connected to the events of creation week.

[1986, p. 302]

So, the rules have been changed. Gentry has attempted to establish new criteria for determining the oldest rocks. But his new criteria fail at every point. Furthermore, he is forced to invoke the supernatural to explain away physical evidence that points to a tremendous amount of geological activity over a long period of time in this region where he found the halos. Since Gentry's God can do anything, he concludes that God created the region to have the features of age and activity that it exhibits and that he made "Genesis rock" look for all the world like a recent intrusion, thereby fooling thousands of geologists.

And, as if making an untestable claim were not enough, Gentry has bolstered his position with a circular argument: "Primordial 218Po halos imply that Precambrian granites, pegmatitic micas, and other rocks which host such halos must be primordial rocks" (1979, p. 474). In short, rocks that contain his halos are by definition the oldest rocks. Since he elsewhere argues that it is only in the oldest rocks that one finds these halos, he is using his halos to date his rocks and his rocks to date his halos.

I have deliberately omitted, because of space limitations, several arguments Gentry uses to support his premise, such as the halos in coal, lead and helium retention in granite, and the artificial synthesis of granite. I have left these items for later discussion, perhaps by others. Any attempt by Gentry to avoid my previous arguments because I left out these latter items or because I have not explained the halos would be irrational and would clearly be a smoke screen to divert attention from the real root of the situation—the specific geology of the sites themselves. Let him answer this directly.

Still, we must give Gentry his due. Nothing in geology fully explains the apparent occurrence of the polonium halos as described by Gentry. They do remain a minor mystery in the field of physics. But this does not mean that no explanations are possible or that it is time to throw in the towel and invoke the "god of the gaps." The generation, preservation, and alteration of the radioactive halos involve complex physical processes that are not yet well understood, and it is quite possible that they are not primordial polonium halos at all. Other explanations include the erasure or modification of the inner halos by the alpha radiation from other isotopes, the migration of uranium-series elements through the rock by fluids or by diffusion accompanied by precipitation of polonium at inclusion sites shortly after it is formed, and the modification of halos by heat and pressure and chemical changes during metamorphism. The very fact that Gentry's halos at these sites occur in areas of unusually high uranium mineralization and metamorphism suggest that halos may be connected with the migration of uranium-bearing fluids through or within the rocks.

What is interesting is that in 1939 Henderson wrote a small paragraph about how these radioactive inclusions got into the biotite:

To provide such a mechanism there seem to be two possible alternative hypotheses, which may be termed magmatic and hydrothermal. On the magmatic hypothesis it is supposed that the constituents of the halo nucleus, including the radioactive parent, crystallized out first from the magma to form the nucleus, and that the biotite later crystallized around it, following the normal order of crystallization from a magma.

[p. 252]

It seems that the magmatic mechanism is the most likely way that radioactive inclusions can get into the biotite without conduits. It satisfies both the rock type locations. As mentioned previously regarding the Silver Crater Mine, the biotite can be shown to have grown in the solid calcite vein dike matrix, engulfing the small radioactive granules. The pegmatite at the Faraday Mine may have been the product of the magmatic process Henderson mentions.

Gentry's case depends upon his halos remaining a mystery. Once a naturalistic explanation is discovered, his claim of a supernatural origin is washed up. So he will not give aid or support to suggestions that might resolve the mystery.

Science works toward an increase in knowledge; creationism depends upon a lack of it. Science promotes the open-ended search; creationism supports giving up and looking no further. It is clear which method Gentry advocates.

Acknowledgements

Help on this project came from many sources, and without their interest this article would never have been written. I gratefully thank for their conversations, letters, phone replies, and visits for clarification of the geology of Ontario the following: Bob Gait of the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto; Louis Moyd of the National Museum of Canada in Ottawa; E. B. Freeman, communications planner of mines and minerals of the Ministry of Northern Development and Mines at Toronto; Norm Trowell, supervising geologist of the Precambrian Division of the Ontario Geological Survey at Toronto; V. C. Papertzian and Dave Williams, geologists with the Ministry of Northern Development and Mines at Tweed; Derek York of the physics department of the University of Toronto; and David Pearson of the department of geology at Laurentian University in Sudbury, Ontario.

Special thanks for their time for our discussions go to Hans Meyn, resident geologist of the Ministry of Northern Development and Mines at Bancroft; Bill Grant, drill core library geologist at Bancroft; and Mike Easton, leader of the Grenville Working Group of the Precambrian Division of the Ontario Geological Survey at Toronto. Help on finding many of the references came from the staff of the Mines Library of the Ontario Geological Survey at Toronto, to whom many thanks are given.

I am also grateful for the input by correspondents John Eichelberger, Wayne Frair, Tom Broadhead, Steve Dutch, Ronnie Hastings, Bob Schadewald, Phil Osmon, Walter Hearn, and Frank Awbrey.

Gratitude is also extended to my editor, G. Brent Dalrymple, for his time on revisions of this manuscript, letters, and helpful suggestions.